Five hundred years ago today, Martin Luther was awarded a doctorate in theology. In 1512, Luther was 28 years old. Seven years before, when Luther was attending law school at the University of Erfurt, a place he called a beerhouse and a whorehouse, lightning struck near where he was riding his horse. This event made Luther realize that he feared for his soul and he made a promise to Saint Anna to become a monk. It was a promise Luther thought he could not break, so he sold his law books and left university to join a monastery in Erfurt. His father was furious at him! How could Luther throw away all the education he received?

After only two years at the monastery, Luther’s sadness and deep introspection was too much for his superiors. Luther was ordained as a priest in 1507 and ordered back to academia where Luther pursued degrees in theology, eventually obtaining a position with the University of Wittenberg’s faculty a mere two days after receiving his doctorate. His position was that of Doctor in Bible.

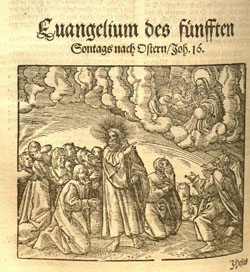

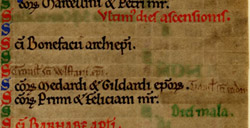

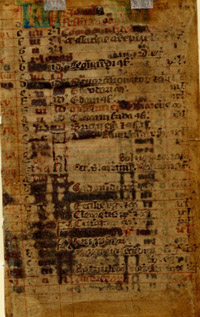

At Special Collections, we have a few items published during Luther’s lifetime and just after. The Kirchen Postilla : Das ist, Auslegung der Episteln und Evangelien an Sontagen und Furnemesten Festen durchs Gantze Jar is one prime example. A rough translation of the title is Church Notes: That is, Interpretation of the Epistles and Gospels for Sundays and Festivals through the Entire Year. This book was meant to be used by Protestant churches all over Germany as a reference book for Protestant ministers while they prepared their Sunday sermons. The book came with two clasps, although one is now missing. It was a chained book, which means that this particular copy that Special Collections possesses must have been chained to a desk. This prevented the possibility of being stolen from the library, church, or monastery where it probably first resided.

At Special Collections, we have a few items published during Luther’s lifetime and just after. The Kirchen Postilla : Das ist, Auslegung der Episteln und Evangelien an Sontagen und Furnemesten Festen durchs Gantze Jar is one prime example. A rough translation of the title is Church Notes: That is, Interpretation of the Epistles and Gospels for Sundays and Festivals through the Entire Year. This book was meant to be used by Protestant churches all over Germany as a reference book for Protestant ministers while they prepared their Sunday sermons. The book came with two clasps, although one is now missing. It was a chained book, which means that this particular copy that Special Collections possesses must have been chained to a desk. This prevented the possibility of being stolen from the library, church, or monastery where it probably first resided.

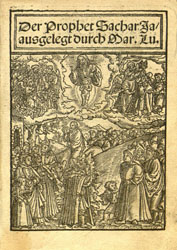

Later, Luther published his German translations of various books of the Bible. Der Prophet Sacharja (The Prophet Zechariah) was published in 1528.

The woodcut illustration on the title page depicts Jesus riding into Jerusalem on a donkey. Zechariah is shown in the upper right hand corner giving the masses the prophecy that Jesus fulfilled that day.

The woodcut illustration on the title page depicts Jesus riding into Jerusalem on a donkey. Zechariah is shown in the upper right hand corner giving the masses the prophecy that Jesus fulfilled that day.

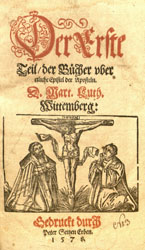

After his death, Luther’s commentaries on the New Testament epistles, Der Erste [Bis Zwelffte] Teil der Bücher, were published. These hefty volumes, twelve in all, not only include thousands of pages of text, but also a large amount of printed margin notes. Like many German tomes of the period, these volumes included metal clasps and hinges to keep the books closed, but all that remains now are the hinges.

On the title page, Martin Luther kneels at Jesus’ left and the Elector of Saxony, who guaranteed Luther’s security while Luther was being pursued by the Cardinal Cajetan, is shown kneeling on Jesus’ right.

On the title page, Martin Luther kneels at Jesus’ left and the Elector of Saxony, who guaranteed Luther’s security while Luther was being pursued by the Cardinal Cajetan, is shown kneeling on Jesus’ right.

Special Collections also owns a few copies of sermons published only a few years after Luther posted his famous 95 Theses. Come by during our operating hours to check out what we have!

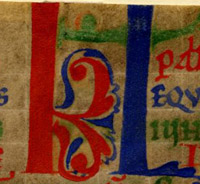

Dr. Rabia Gregory, an assistant professor in the Religious Studies department at the University of Missouri, is the focus of the first Teacher Spotlight of the new school year. Her primary interest is in medieval women’s religious literature, and she can often be found teaching courses at Mizzou on Historical Christianity, and Women and Religions. Dr. Gregory is a frequent visitor to Special Collections and has often brought her classes to learn about the primary sources we have here. We were pleased to get a chance to talk to her at the beginning of the semester.

Dr. Rabia Gregory, an assistant professor in the Religious Studies department at the University of Missouri, is the focus of the first Teacher Spotlight of the new school year. Her primary interest is in medieval women’s religious literature, and she can often be found teaching courses at Mizzou on Historical Christianity, and Women and Religions. Dr. Gregory is a frequent visitor to Special Collections and has often brought her classes to learn about the primary sources we have here. We were pleased to get a chance to talk to her at the beginning of the semester.

As part of a class session in Special Collections, your students will have hands-on access to the most inspiring and intriguing materials the Libraries have to offer. They will learn research skills that go beyond databases – the ability to track down sources, make connections among documents, and read the content of the page alongside physical evidence. Most importantly, they will discover an enthusiasm and engagement with their subject that will take their studies far beyond their textbooks.

As part of a class session in Special Collections, your students will have hands-on access to the most inspiring and intriguing materials the Libraries have to offer. They will learn research skills that go beyond databases – the ability to track down sources, make connections among documents, and read the content of the page alongside physical evidence. Most importantly, they will discover an enthusiasm and engagement with their subject that will take their studies far beyond their textbooks.