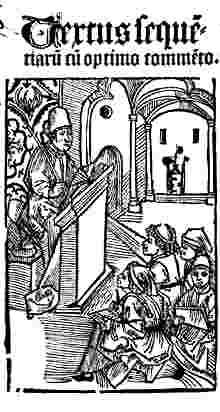

Textus seque[n]tiaru[m] cu[m] optimo comme[n]to, was one of a few incunabula we acquired last year. Published in Cologne by Heinrich Quentell in 1496, the book is a collection of Sequences with extensive comments and explanations for students by a well known Nederlandish scholar and grammarian Hermann Torrentinus (ca.1450-1520)

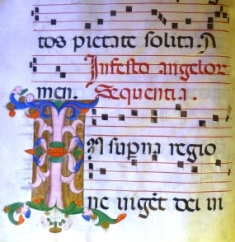

Liturgical Sequences were an integral part of the Roman Mass. The Catholic Encyclopedia (1913) defines the Sequence (Sequentia, or Prose [Prosa]),-as "the liturgical hymn of the Mass which occurs before the Gospel, while the hymn (poetry), belongs to the Breviary." In other words, while hymns were part of the Mass from the earliest times, sequences originated in the ninth century as "texts written to accompany what had hitherto been a wordless musical extension of the final -a of the Alleluia at the end of the antiphon sung between the Epistle and Gospel." * Some scholars think that sequences came from the Byzantine rite; others insist that it was an independent invention of the Roman Church. **

The word "Sequentia" was first introduced in the 9th century by Notker Balbulus (ca. 840-912), monk of St. Gall (Switzerland nowadays), who put some liturgical texts into rhythmical melodic phrases. The structure of these sequences was completely new — it was none of the traditional structure of Latin sacred verse, but was "unfolding in a vigorous series of free rhetorical periods, cast in the sonorous cadences of classical Latin diction, and, in the Notker case, –in a more exuberant diction rich with assonance." ***

One of the best known sequences today is the Christmas carol Adeste Fideles, known in English as "O Come, All Ye Faithful", also the Marian sequence Stabat Mater by Jacopone da Todi.

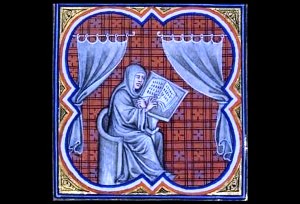

Writing commentaries on sequences was, it would appear, a quite common literary pursuit in the twelfth or thirteenth century. It was part of the extensive commentary literature, especially widespread in the German-speaking countries. Besides Hermann Torrentinus we know the names of Jacob Wimpheling (1450-1528), Caesarius von Heisterbach (ca. 1180 – ca. 1240), and Johannes Adelphus (1445-1522). Such commentaries likely played an important didactic role in schools or universities, depending on the depths of the analysis, which ranged from a basic explanation of the meaning of a phrase to a philosophical treatise.

Our book contains detailed comments by Torrentinus, including analysis of Latin phrases and their component parts in the 51 sequences written by Notker Balbulus. These are on the feasts of the Nativity of Christ (De Nativitate D[omi]ni), St. Stephen, St. John, The Innocents (slain by Herod), the Holy Trinity, St. Nicholas, St. Elizabeth, St. Katherine, the Virgin Mary, the Ascension, the Conception of the Virgin Mary, and many others.

A short introduction states the purpose and subject of the book: "laus divina" –Divine glory, than follows an explanation of the book's structure. Torrentinus then dwells on the meaning of the first sentence of the sequence for the Nativity of Christ (Christmas), and the grammatical structure of it. His explanations of some of the words are quite curious, for example, the word "diabolus":

Grates nunc omnes reddamus domino deo

Qui sua nativitate nos liberavit de dyabolica potestate.

(Item dyabolica est nome[n] adiectivium derivatum a nomine dyabolus. A dya q[uod] est duo…)

The word "dyabolica" is the adjective, derived from the noun "dyabolus".

"Dya" means "duo"– double, and "bolos" – sting, as if {it were} a double sting which strikes our bodies and souls– says the author.

This explanation shows that the man, known as a great grammarian of his time, apparently didn't have much Greek, giving a peculiar interpretation of the original Greek word: "Diabolus (from Greek: Δια + βάλλειν), where Δια — penetration through the line from one end to the other, often the effect of weapons, division, like in "diaphragm","diameter" ,diacritic", and βάλλειν –-"throw", like in ballistics, so the whole word means a "divider", "slanderer"," backbiter".

Most probably this book was intended for beginners studying Liturgy who knew Latin enough to understand instructions and explanations of the book. It has multiple marginal notes, comments by several contemporary owners, corrections, and in some cases an empty space, left for the illuminated or rubricated initial letter, is filled in pen or pencil.

Curiously enough, it doesn't have a colophon. The only date mentioned in the text could be found on the verso of page signed [3iij], Folium iiij, where the author, while speaking of the Nativity of Christ, explains the principles of dating: "Annos dat ab Adam donec Xr[istu]s homo fact[us]. Sed a nativitate[m] Xri[st]i usque ad nu[n]c scribitur anno domini. Mcccclxxxxvi", ("Dates used to be given from Adam to Christ's incarnation. But from the nativity of Christ onwards they are written as Anno Domini .1496"} which gives us 1496 as a possible date of publication.

Who was the man to whom these comments are attributed?

Torrentinus belongs to that huge crowd of late mediaeval scholars whose names are known nowadays only to a small number of enthusiastic book lovers or medievalists.

Hermann von der Beeke, known mostly under his Latinized name Torrentinus, or Torrentius (meaning "brook" or "torrent, as translated from the original word beeke ) was born around 1450 in Zwolle, Netherlands, about 80 miles north- east of Amsterdam. He received initial education in his native town in the School of the Brethren of the Common Life (Fratres Vitae Commune), a Roman Catholic religious community founded in the 14th century by Gerard Groote, and devoted to education and teaching. The brethren didn't take up irrevocable vows, in difference from a regular monastic community, but led a simple and chaste life, practicing ascetic discipline and devoting all their time to attending Divine services, reading, and labors. They lived in the common houses and had meals together.

The year 1490 finds Torrentinus in Groningen, teaching rhetoric in the Brethren of the Common Life School. After the death of his father he had to return to Zwolle to help and support his mother, where he took a position of school teacher. Torrentinus is known as an editor of Virgil's Eclogues and Georgics (1502), and as the author of a Elucidarius Poeticus (dictionary of proper names of people, places, plants, etc., encountered in history and poetry) (1498).

He revised and edited the first part of Alexander de Villa Dei's standard Latin grammar, the Doctrinale (1504), and wrote several small books for use in his school. Around 1508 his eyesight was failing and Torrentinus had to leave his position as Head of Zwolle Brethren School. He died in Zwolle in 1520.

It looks like an uneventful life. Appearances often deceive, however. In Groningen Torrentinus came under the influence of such a forceful figure as Wessel Gansfort whose anti-papal sentiments and rather unorthodox interpretations of the Bible****** were known. Some sources mutedly suggest that Torrentinus also might have entertained some peculiar ideas; however we know so little about him that it's hard to prove.

Our copy is bound in half red leather with decorated endpapers and boards, its spine is decorated with floral motif between raised bands in gilt and embossed with "c.1494". Marginal annotations in Latin are in contemporary ink. Initial spaces are not rubricated; on rear lining paper there is a bookplate of Glenmore Whitney Davis, journalist for the New York Globe (New York daily newspaper published till 1923).

References and notes:

*Messenger, Ruth, The Medieval Latin Hymn, Washington DC, 1953

Kaske, R.E., Medieval Christian Literary Imagery: a guide to interpretation, Toronto.

**In the Byzantine Church/Orthodox Church it is called Alleluaria and was established on the First Council of Nicaea in 325 AD. See: Дмитревский И. И. Историческое, догматическое и таинственное изъяснение Божественной Литургии, p. 234 : "Между пением Аллилуя возглашаются чтецом стихи, называемые Аллилуариями"

***Richard Crocker, The Early Medieval Sequence, U of California Press, 1977.

**** Erika Kihlman, Expositiones sequentarum. Medieval Sequence Commentaries and Prologues. Editions with Introductions. Stockholm University,2012?

***** Though Gansfort firmly stands on a Catholic ground and he never had brushes with the Inquisition, his writings were on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Catholic Encyclopedia)

Bibliography:

John Edwin Sandys (1844-1922) A History of Classical Scholarship: From the Revival of Learning to the End of the Eighteenth Century in Italy, France, England and the Netherlands.

Contemporaries of Erasmus: a biographical register of the Renaissance and Reformation. Ed. Peter G. Bietenholz. Toronto, U of Toronto press, 1987