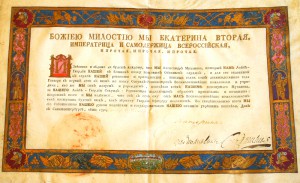

Travel guides began to appear in the eighteenth century with the rise in popularity of the Grand Tour. Wealthy young men traveled the continent, seeking to experience culture and the arts and enjoying European society. While the outbreak of the French Revolution curtailed the practice, peacetime brought tourists back to Europe.

Travel guides began to appear in the eighteenth century with the rise in popularity of the Grand Tour. Wealthy young men traveled the continent, seeking to experience culture and the arts and enjoying European society. While the outbreak of the French Revolution curtailed the practice, peacetime brought tourists back to Europe.

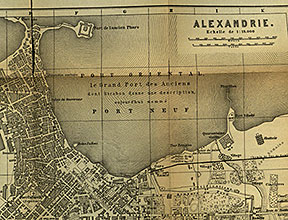

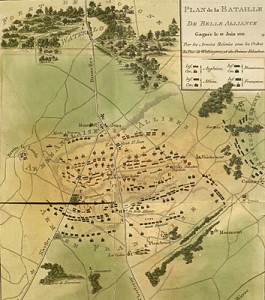

Special Collections has several guidebooks from this period. Mariana Starke’s Letters from Italy (London, 1800) reassured travelers that travel was safe and that the cities of Italy had not been robbed of their artwork. Starke gave her readers practical information about specific sites. Karl Baedeker published his first guidebook in 1839, basing the content on his personal travel experiences and including detailed maps. These guides became extremely popular. The firm is still producing guidebooks today. While not technically a guidebook, Bachelder’s Popular Resorts and How to Reach Them (Boston, 1875), gave travelers to the United States guidance on how to reach newly establish National Parks in the west.

Special Collections has several guidebooks from this period. Mariana Starke’s Letters from Italy (London, 1800) reassured travelers that travel was safe and that the cities of Italy had not been robbed of their artwork. Starke gave her readers practical information about specific sites. Karl Baedeker published his first guidebook in 1839, basing the content on his personal travel experiences and including detailed maps. These guides became extremely popular. The firm is still producing guidebooks today. While not technically a guidebook, Bachelder’s Popular Resorts and How to Reach Them (Boston, 1875), gave travelers to the United States guidance on how to reach newly establish National Parks in the west.

Advice from our guidebooks:

Avoid local fauna:

“The sting of a scorpion (seldom dangerous) or bite of a snake is usually treated with ammonia.”

—Baedeker’s Lower Egypt(Leipzig, 1895)

How to pack:

“A soft or compressible portmanteau is not recommended, as the “Skydsgut”, who is sometimes a ponderous adult, always sits on the luggage strapped on [the pack horse]. A supply of stout cord and several straps will be found useful, and a strong umbrella is indispensable.”

—Baedeker’s Norway and Sweden (Leipzig, 1879)

Visiting a National Park:

Visiting a National Park:

“If the National Park of the Yellowstone be the objective point, the tourist will continue on the Union Pacific Railroad to Corinne, Utah, at present the nearest approach by rail. From Corinne, the trip is completed partly by stage and by saddle, but should only be undertaken by person of strong physical endurance, after special preparation.”

Popular Resorts and How to Reach Them (Boston, 1875)

“The Cappella Sistina contains some of the finest frescos in the world, namely, The last Judgement, by Buonarroti, immediately behind the alter, and on the ceiling, God dividing the light from the darkness, together with the Prophets and Sibyls, stupendous works by the same great Master !!!!!”

Letters from Italy (London, 1800)

Starke’s use of multiple exclamation points following her descriptions functioned as a kind of rating system. Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescos earns the highest praise, a rare five exclamation marks.

Starke’s use of multiple exclamation points following her descriptions functioned as a kind of rating system. Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescos earns the highest praise, a rare five exclamation marks.

Take a sweater:

Letters from Italy (London, 1800)

Local insects:

Baedeker’s Norway and Sweden (Leipzig, 1879)

Where to stay in Vienna:

Letters from Italy (London, 1800)

Advice for cigar aficionados in Egypt:

Advice for cigar aficionados in Egypt:

Baedeker’s Lower Egypt (Leipzig, 1895)

Special Collections has several of Baedeker's Guides in our collection. Search for Karl Baedker (firm) in the Merlin catalog. Limit your search to Special Collections.

Special Collections has several of Baedeker's Guides in our collection. Search for Karl Baedker (firm) in the Merlin catalog. Limit your search to Special Collections.

The 2012 Summer Olympic Games in London begin later this month on July 27th. For nineteen days, athletes from 205 countries will compete in 300 events for gold, silver, and bronze medals. Over one billion people watch the Summer Olympics, when it is held every four years. This month, the colonnade of Ellis Library is showcasing both the history of the Olympic Games and this year’s host city, London. As you are walking through the library, why don’t you stop by one of the displays and learn about some of the most memorable moments in Olympics history, or the history and culture of the only city in the world to host the Summer Olympics three times.

The 2012 Summer Olympic Games in London begin later this month on July 27th. For nineteen days, athletes from 205 countries will compete in 300 events for gold, silver, and bronze medals. Over one billion people watch the Summer Olympics, when it is held every four years. This month, the colonnade of Ellis Library is showcasing both the history of the Olympic Games and this year’s host city, London. As you are walking through the library, why don’t you stop by one of the displays and learn about some of the most memorable moments in Olympics history, or the history and culture of the only city in the world to host the Summer Olympics three times.