This semester, Special Collections will be turning the spotlight on our patrons each month by highlighting teaching and student work inspired by the collections. This post kicks off the semester and focuses on the teaching of Julie Christenson. Julie visited Special Collections with her section of Humanities 2111H (The Ancient World; part of the Honors Humanities Sequence). We corresponded with her via email to get her thoughts on Special Collections and undergraduate instruction.

SC: Can you give us some information about yourself?

I am a graduate student instructor in the English department. I am writing my dissertation on the poetics of commemoration in medieval England. I am interested in the poetic strategies of texts designed to commemorate events and figures.

SC: How did you incorporate Special Collections into your teaching last semester?

My students came for two visits. On their first visit, Kelli Hansen introduced several pieces from the collections that were relevant to the texts my students were studying. For their second visit, each student worked with one of the pieces that had been introduced during the previous session. They used their observations as the basis of a 2–3 page manuscript analysis.

SC: What outcomes resulted from your class visits? What were the effects on your students?

I think it’s good for students to realize that classical and medieval literature served a vital function within much different material, social, and aesthetic frameworks. There is just no comparison to experiencing a one-of-a-kind book, seeing the hole in the parchment where the animal had been bitten by a mosquito, to seeing the pages darkened from generations of hands turning the pages.

SC: What advice would you give to faculty or instructors interested in using Special Collections in their courses?

SC: What advice would you give to faculty or instructors interested in using Special Collections in their courses?

I understand the hesitation to take time out of our already cluttered schedules to what might seem like a frill, but my advice is to squeeze in a visit. It will enhance the work you do everyday in the classroom. Your students will be able to forge an experiential connection with the periods you are studying. That experiential basis convinces and inspires in a way that complements the work we do in the classroom.

Stay tuned – tomorrow we'll be sharing some of the student work that resulted from Julie Christenson's class visit.

exams. Of course, Special Collections is always ready to help. This week, we’re sharing a 280-year-old secret from the

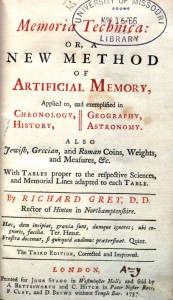

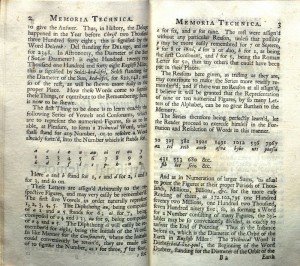

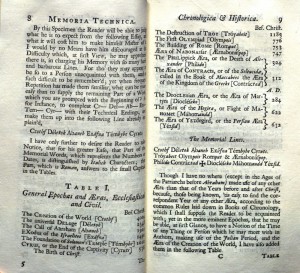

exams. Of course, Special Collections is always ready to help. This week, we’re sharing a 280-year-old secret from the  The words in brackets are the mnemonic devices, with the code at the end that represents the year in letters. If a student were called upon in an exam to produce an entire chronology of world events (as students often were in the eighteenth century), he could simply remember what Grey calls the “Memorial Line”: Diocleseko Mahomaudd Yezsid. Grey points out that the system is also adaptable to geography, astronomy, weights and measures, and the study of ancient coins.

The words in brackets are the mnemonic devices, with the code at the end that represents the year in letters. If a student were called upon in an exam to produce an entire chronology of world events (as students often were in the eighteenth century), he could simply remember what Grey calls the “Memorial Line”: Diocleseko Mahomaudd Yezsid. Grey points out that the system is also adaptable to geography, astronomy, weights and measures, and the study of ancient coins.

readers, his work was hugely popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Memoria Technica remained in print for over 130 years, and was in fact the only pre-1800 book on memory to remain in use for so long.

readers, his work was hugely popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Memoria Technica remained in print for over 130 years, and was in fact the only pre-1800 book on memory to remain in use for so long.

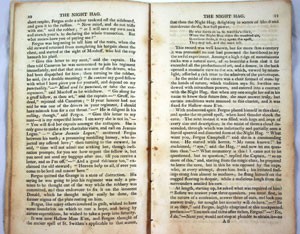

In honor of Halloween, we're posting an excerpt from one of the horror stories in the rare book collection,

In honor of Halloween, we're posting an excerpt from one of the horror stories in the rare book collection,

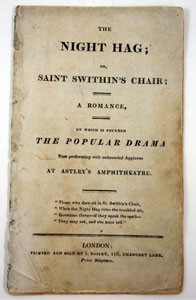

This pamphlet purports to be "a romance, on which is founded the popular drama now performing with unbounded applause at Astley's Amphitheatre." Several plays were produced under this title in the early nineteenth century, featuring Fergus Campbell, his unfortunate aunt, and the rest of the characters in the romance. Indeed, the first of these plays was performed at Astley's Amphitheatre and ran in September and October 1820. The playbill for this production said "The Idea from which the Subject is arranged [is] taken from the Interesting Legend of St. Swithin's Chair, in Walter Scott's Popular Novel of Waverly."

This pamphlet purports to be "a romance, on which is founded the popular drama now performing with unbounded applause at Astley's Amphitheatre." Several plays were produced under this title in the early nineteenth century, featuring Fergus Campbell, his unfortunate aunt, and the rest of the characters in the romance. Indeed, the first of these plays was performed at Astley's Amphitheatre and ran in September and October 1820. The playbill for this production said "The Idea from which the Subject is arranged [is] taken from the Interesting Legend of St. Swithin's Chair, in Walter Scott's Popular Novel of Waverly."

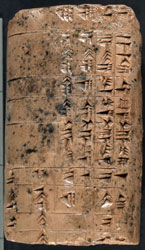

As far as we know, this cuneiform tablet dates to around 2500 B.C.E., making it the oldest item held in Special Collections (it predates the next oldest item, an Egyptian scarab seal, by about 500 years).

As far as we know, this cuneiform tablet dates to around 2500 B.C.E., making it the oldest item held in Special Collections (it predates the next oldest item, an Egyptian scarab seal, by about 500 years).

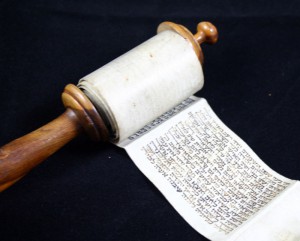

If you guessed that the scroll represents the oldest book form in Special Collections, you were right! The scroll predated the codex (the form we usually associate with a book nowadays) by thousands of years.

If you guessed that the scroll represents the oldest book form in Special Collections, you were right! The scroll predated the codex (the form we usually associate with a book nowadays) by thousands of years.

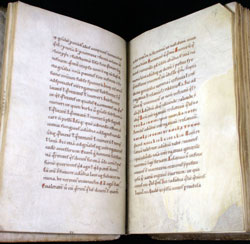

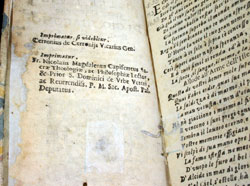

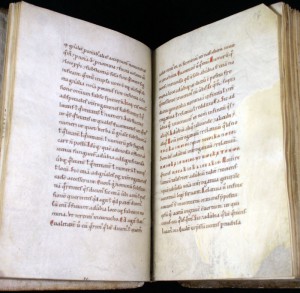

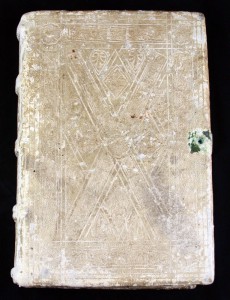

This manuscript copy of De Constructione by Priscianus dates to around 1150 A.D. Although Special Collections holds manuscript fragments that are older, this is the oldest complete book in the collection. It is a work on grammar, written in Latin with passages in Greek.

This manuscript copy of De Constructione by Priscianus dates to around 1150 A.D. Although Special Collections holds manuscript fragments that are older, this is the oldest complete book in the collection. It is a work on grammar, written in Latin with passages in Greek.

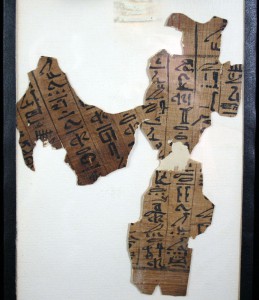

Dating from approximately 1500-1100 B.C.E., this fragment from the Egyptian Book of the Dead isn’t the oldest item in Special Collections – but it is the oldest piece of writing on papyrus in Special Collections.

Dating from approximately 1500-1100 B.C.E., this fragment from the Egyptian Book of the Dead isn’t the oldest item in Special Collections – but it is the oldest piece of writing on papyrus in Special Collections.