Jennifer Para is a freshman from Rogers, Arkansas, majoring in business. As part of Julie Christenson's section on the ancient world, part of the honors humanities sequence, Jen and her classmates worked with rare and historic materials in Special Collections, including ancient materials and fifteenth- and sixteenth-century editions of the classics. Jen shares her insights and reactions below.

Jennifer Para is a freshman from Rogers, Arkansas, majoring in business. As part of Julie Christenson's section on the ancient world, part of the honors humanities sequence, Jen and her classmates worked with rare and historic materials in Special Collections, including ancient materials and fifteenth- and sixteenth-century editions of the classics. Jen shares her insights and reactions below.

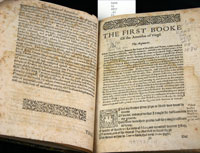

Glancing through rare books at Ellis Library, a certain leather bound novel with a delicate design imprinted into the spine catches your eye. The marbled paper cover reminds you of exquisite stones with white and gold specks reflecting the bouncing sun, meshed together in a pond of blood. Touching the book, you are surprised at its smoothness, and you wonder why the book does not fall apart at your caress. On the book’s spine you notice gold lettering revealing the title of the book: Aeneidos. This epic poem is a 1583 copy of Phaer and Twyne’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid.

Glancing through rare books at Ellis Library, a certain leather bound novel with a delicate design imprinted into the spine catches your eye. The marbled paper cover reminds you of exquisite stones with white and gold specks reflecting the bouncing sun, meshed together in a pond of blood. Touching the book, you are surprised at its smoothness, and you wonder why the book does not fall apart at your caress. On the book’s spine you notice gold lettering revealing the title of the book: Aeneidos. This epic poem is a 1583 copy of Phaer and Twyne’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid.

Flipping through the book, you observe old English type and strain your eyes to read it. You come to the beginning of a chapter with an intricate black border in which an “Argument” gives a summery of the chapter. As you look through the epic poem, you see no page numbers, only words at the bottom of each page. Curious, you ask the librarian. She informs you that the printing process included folding the papers together, using the first and last words of a page to ensure the correct order.

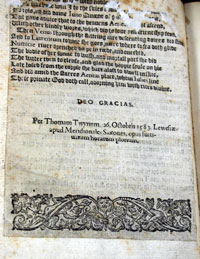

At the end of each chapter there seems to be a Latin copyright, and you also notice small printed notes in the margins. Between books twelve and thir teen you find the authors’ letter to their readers. Phaer and Twyne intended their translation of the Aeneid to be read by “maisters and students of universities,” who “will not bee too much offended,” by their raw translation, and “pray they will correct the errors escaped in the printing.”

teen you find the authors’ letter to their readers. Phaer and Twyne intended their translation of the Aeneid to be read by “maisters and students of universities,” who “will not bee too much offended,” by their raw translation, and “pray they will correct the errors escaped in the printing.”

Curious about Phaer and Twyne, you begin researching for more information. Thomas Phaer, a native to Pembrokeshire, translated The Aeneid into one of the oldest meters in English, the fourteener. According to scholars, it was a good attempt, but not attractive. Unfortunately, Phear died while translating the tenth book. Not wanting to leave the work unfinished, Thomas Twyne edited and finished the last two and a half books in 1573.

You look through the book once again. This copy is not an original nor a textbook; there are no handwritten notes anywhere. But in book ten,  you see calligraphy and make out words “Hugh Bateman”, “Thomas Payne”, “1767 London”, “Dronfield”. Partaking in more research, you find record of several Hugh Batemans at Dronfield.

you see calligraphy and make out words “Hugh Bateman”, “Thomas Payne”, “1767 London”, “Dronfield”. Partaking in more research, you find record of several Hugh Batemans at Dronfield.

You come to the conclusion that this epic-poem, due to its lack of use and penmanship practicing, was most likely a “coffee-table book”. Its gorgeous cover could capture the eyes of any person, but its translation made it very difficult to read. You picture in your mind this epic poem, sitting on a rosewood desk, collecting dust, until a man opens it up to dab ink off his quill. Closing the book, you sigh, knowing you are only partaking in guesswork. You wonder what conversations it has overheard, who read its pages, and how it ended up at the Ellis Library at the University of Missouri. If only books could talk.

Have an outstanding student you'd like to nominate for the Spotlight? Email SpecialCollections@missouri.edu.