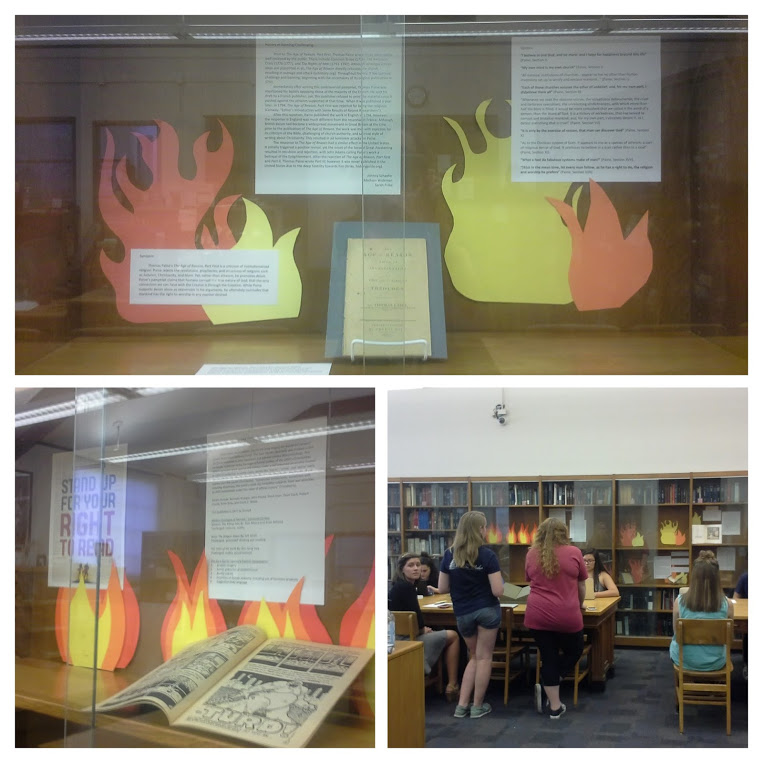

This post is part 6 of our continuing series on Dr. Juliette Paul's English 4300 class and their research on an early American manuscript in Special Collections.

by Jon Crecelius

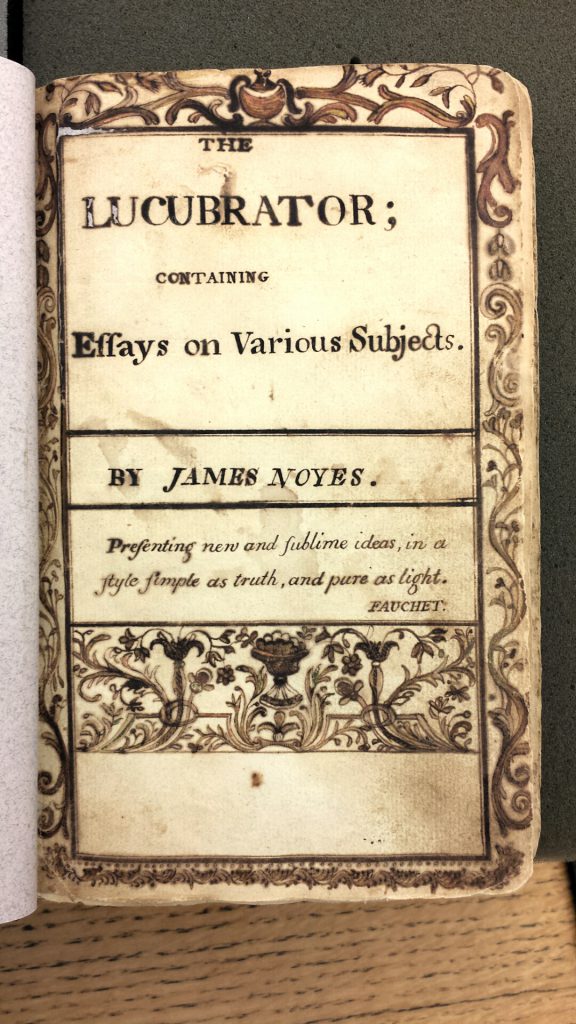

Though we don’t have the technology to travel back to the past, we can still piece together clues that give us a glimpse of what the past was like. In conducting research on The Lucubrator, I did exactly that. My interests leaned towards the intellectual and literary cultures of post-revolutionary America, and how they might have influenced the mysterious author of the manuscript, called James Noyes on the title page.

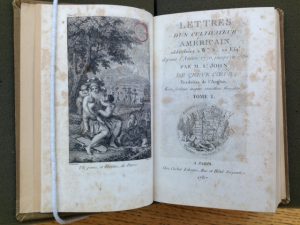

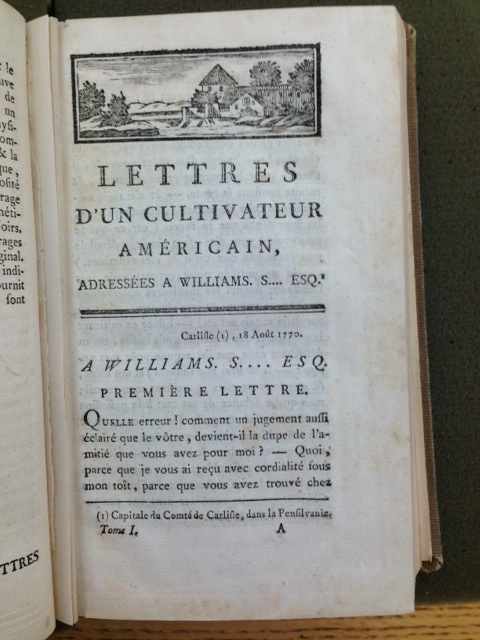

Some of the most notable writers of eighteenth-century America were none other than the “Founding Fathers.” Men such as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and James Madison, with their works entitled Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), Poor Richard’s Almanack (1732-58), and The Federalist Papers (1787-88), all wrote well known publications that would have shaped the literary and social culture of the manuscript author’s time. But these men were not the only authors writing important pieces in and about early America. One important, but overlooked, author is J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur (1735-1813), an influential French immigrant farmer who lived in New York.

The writings of Crèvecoeur espouse the type of freethinking, industriousness, and morally minded spirit so often dictated by The Lucubrator’s author. In his famous essay, “What is an American?,” Crèvecoeur asserts “We are all animated with the spirit of industry which is unfettered and unrestrained because each person works for himself” (2). This portrait of Americans, driven by a strong work ethic, is found also in Jefferson’s writings and may be compared to the industrious writer we meet in The Lucubrator. More significant, however, is that all three writers—Crèvecoeur, Jefferson, and the author of the manuscript—express admiration for the American farmer and the pastoral joys of agricultural life that many believed came with it. In one passage of his Notes, Jefferson writes “Those who labour in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people, whose breasts he has made his peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue. It is the focus in which he keeps alive that sacred fire, which otherwise might escape from the face of the earth” (179). Likewise, the author of The Lucubrator writes in an essay entitled “On Agriculture”: “If gentleman in the highest walks of society possessed a taste for the amusement of gardening, the cultivation of fruit trees, and other branches of agriculture, it would perhaps contribute as much to health and innocence, as to national independence and prosperity.”

If James Noyes of Atkinson is the author of The Lucubrator, he seems to have been a man of high ideals and strong morals. In my opinion, though he makes himself out to be an important thinker, Noyes is mostly distilling the ideas of writers who came before him. However, this does not make his work unimportant. It is still, despite its enigmatic character, an important discovery that adds to our knowledge of the early American landscape; and, because this work is one that has been previously unstudied, it shows us how those people forgotten by history thought and lived.

Works Cited

St. John, James Hector. "What Is an American?" Letters From an American Farmer. 1782.

National Humanities Center. Web. 15 Apr. 2016.

Jefferson, Thomas. Notes on the State of Virginia. The Federalist Papers Project. Web. 16 Apr. 2016.

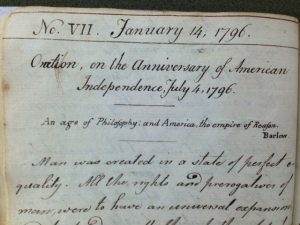

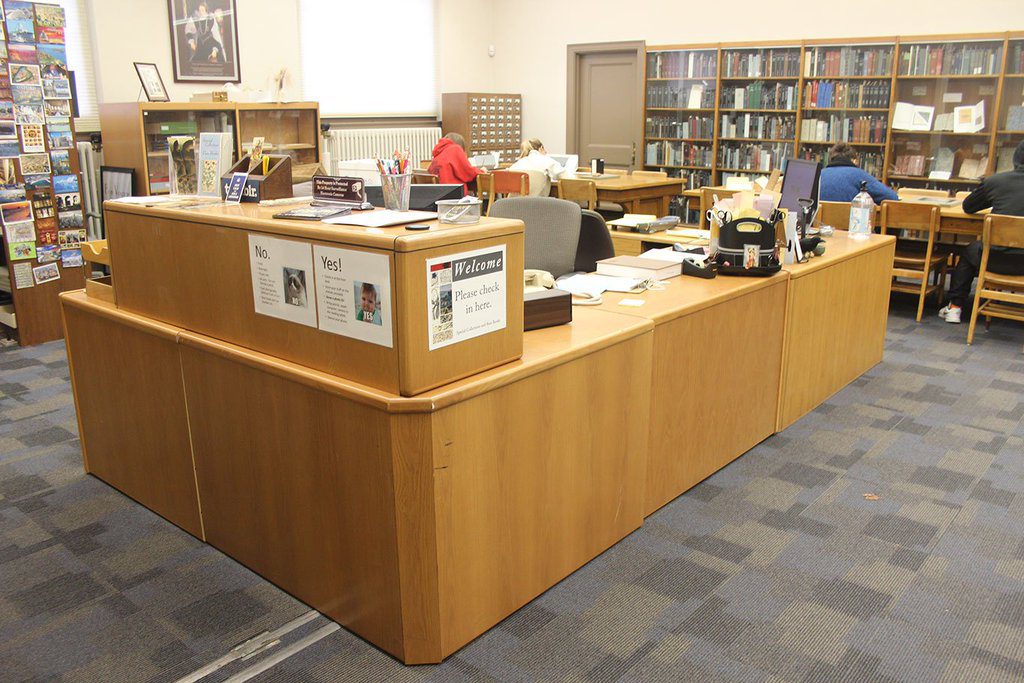

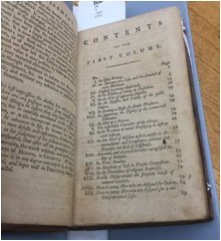

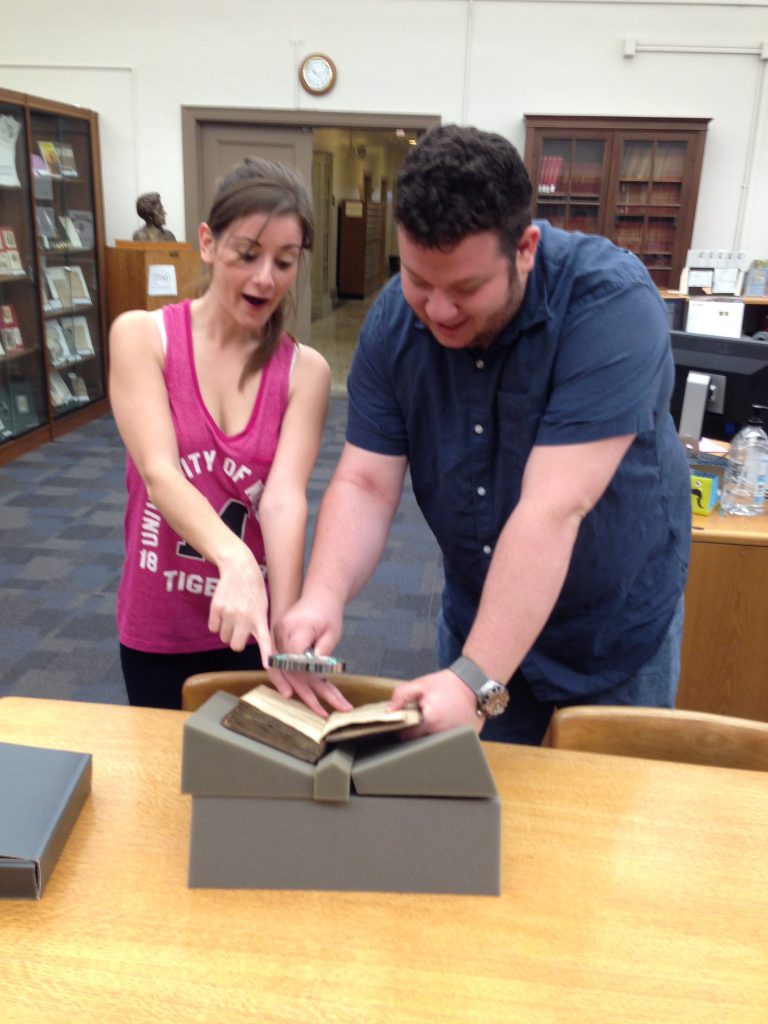

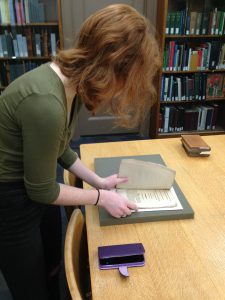

People often forget about the multitude of manuscripts that are forever lost, which is why discovering one previously unknown seems all the more incredible. Unearthing a mysterious manuscript entitled The Lucubrator (1794-97) is exactly what our class did this semester (English 4300, Spring 2016). As we studied early American literature, it made sense for us to examine the strange, little-known manuscript held in our Special Collections and Rare Books Library. Filled with essays illustrating the culture of the early United States, The Lucubrator seems to belong to the literature we studied. We believe the manuscript was once owned by James Noyes (1778-99), a young, patriotic, and accomplished New England writer whose name appears on the title page.

People often forget about the multitude of manuscripts that are forever lost, which is why discovering one previously unknown seems all the more incredible. Unearthing a mysterious manuscript entitled The Lucubrator (1794-97) is exactly what our class did this semester (English 4300, Spring 2016). As we studied early American literature, it made sense for us to examine the strange, little-known manuscript held in our Special Collections and Rare Books Library. Filled with essays illustrating the culture of the early United States, The Lucubrator seems to belong to the literature we studied. We believe the manuscript was once owned by James Noyes (1778-99), a young, patriotic, and accomplished New England writer whose name appears on the title page.