Mary Parker, a student in Dr. Rabia Gregory's History of Christianity class, is sharing her paper on an incunable from Special Collections. We're using her words and images with permission. – KH

Girolamo Savonarola, author of this epistola, was born to a well off family from Padua with his grandfather being a physician and professor at a medical college. Girolamo planned to study medicine as his grandfather had after getting his bachelor’s degree, but instead dropped out to join a Dominican monastery in Bologna without informing his family of his decision until he was already gone (Kirsch 2015).

From early in his life Girolamo felt strongly about the “depravity” of the era that he was living in. After years of study in the monastery and in Ferrara, he was sent to Florence to preach. His career took off after he became prior at the monastery of San Marco. While there, he preached strongly against paganism and the immoral life of many Florentines, as well as against the Medici’s, current rulers of Florence (Amelung 2015).

When Lorenzo de ’Medici died, Savonarola developed into a political as well as a religious leader and began thinking of setting up a theocracy of sorts. His sermons were often very biting and intense as he preached against the immoral life of members of the Roman Curia, against Pope Alexander VI, and against the evils of princes and courtiers. The Medici family was driven out of power due to the people’s hatred of the family’s tyranny and immoral lives. The French king ended up coming to Florence and setting up a theocratic democracy with Christ being the King of Florence and a council that represented all citizens. Girolamo was not directly involved with the government but his sermons and teachings held large influence in the city. Eventually, a sort of moral police force was set up that spied on and denounced people who did not follow the moral guidelines put forth by Girolamo (Kirsch 2015).

His daring and passionate sermons eventually lead to a conflict with Pope Alexander VI. In 1495, the pope commanded Girolamo to go to Rome and defend himself against all of the accusations held against him. He declined saying that his health prevented him and that the journey would be too dangerous. Shortly after, the Pope declared that Girolamo was no longer allowed to preach and that he also could no longer be the prior of the San Marco monastery. Girolamo attempted to justify his actions; and when it came to his preaching, he said he always submitted himself to the Church. A new papal Brief was written that maintained his ban on preaching but judged easily his actions (Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2015).

Girolamo disobediently still preached in Florence with sermons that were strongly against the so called crimes of Rome. All this lead to a possible schism in the Church; therefore, the Pope needed to step in and do something. Girolamo was eventually excommunicated in 1497, but this did not stop Girolamo from celebrating Mass on Christmas Day, distributing Holy Communion, and then subsequently preaching in the cathedral. While all this was occurring, opponents to Girolamo were becoming more powerful and after an attempt at an ordeal by fire; the general people began to turn against Girolamo. The San Marco monastery was attached and he was taken prisoner and eventually condemned to death "on account of the enormous crimes of which they had been convicted". He was then hanged and after his body was burnt at the stake (Kirsch 2015).

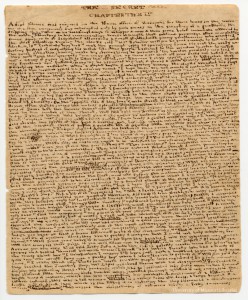

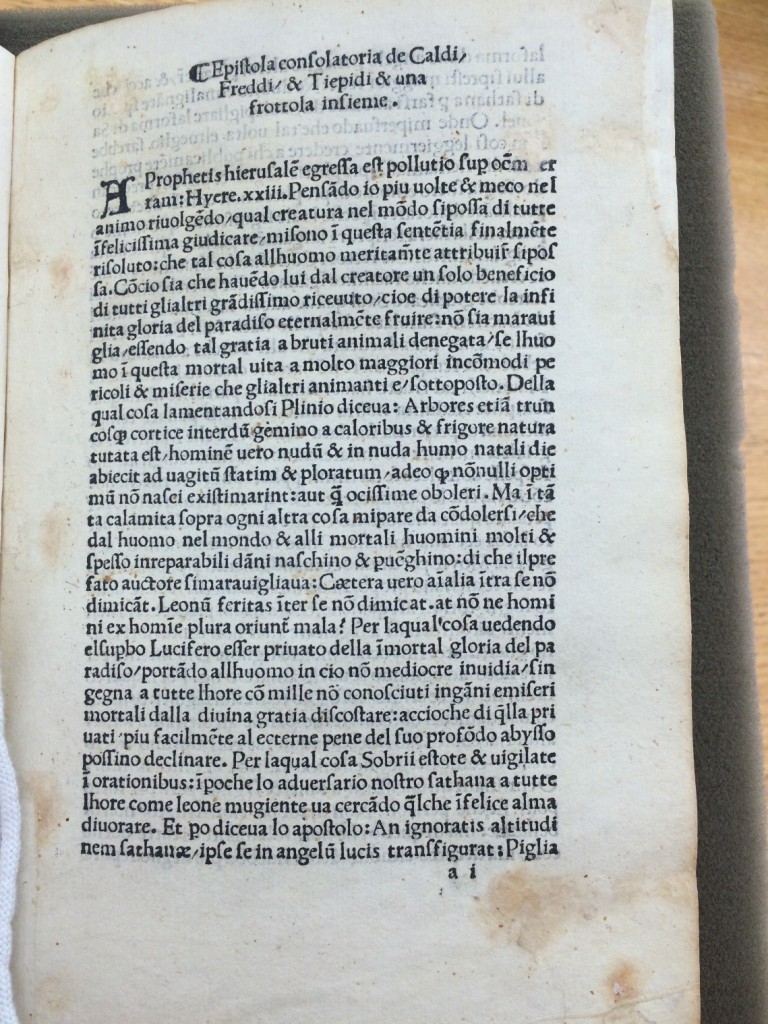

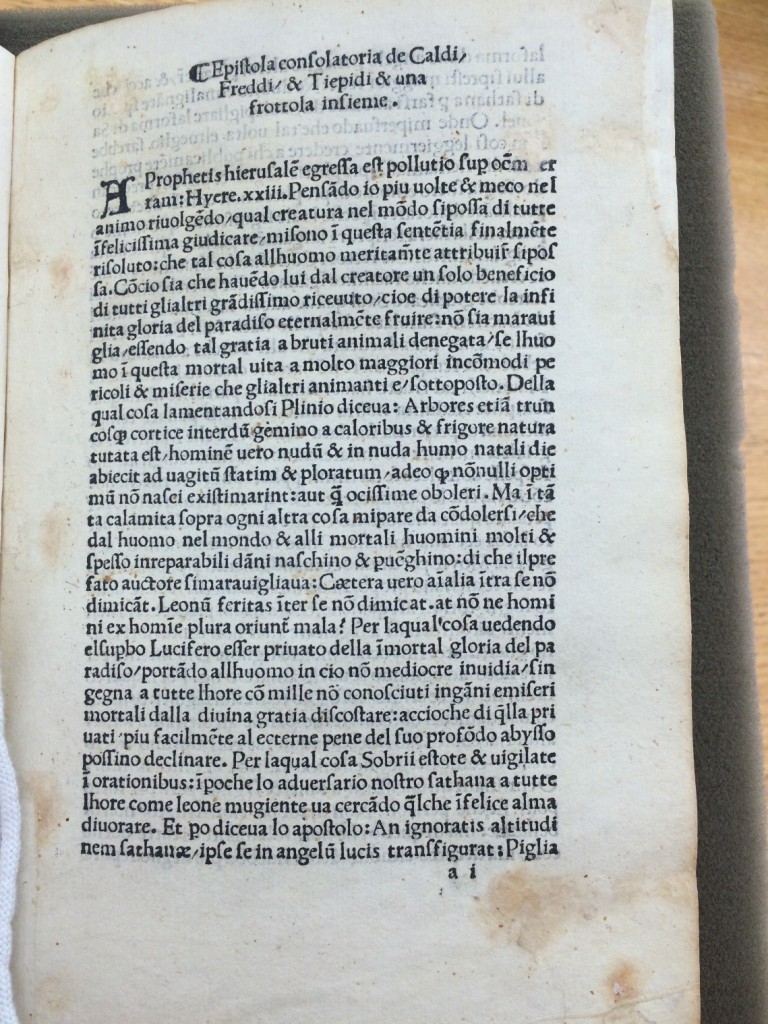

Epistola consolatoria de Caldi, Freddi, & Tiepidi & una frottola insieme is thought to have been published in 1496 by Lorenzo Morgiani and Johann Petri, which means that Girolamo most likely preached this sermon after the second papal Brief commanded him to no longer preach. The epistola is largely speaking about being a lukewarm Christian or even falling prey to Satan’s deceit as can be seen in the later part of my attempt at a translation of the first page of the epistola.

The prophets of Jerusalem went forth: Hyere. xxiii. I Pensado, in happy mood, turn to judge you and see what creatures you are, and the misnomers of this problem should be finally resolved. That what each man deserves to be attributed to him, he will surely now know. To see whether to his benefit he will be shown as great by the creator, the power of the infinite glory of Heaven eternal and its benefits; but being such brutish animals man lives in denial and his mortal needs cause him to undergo more uncomfortable dangers and miseries than other animals undergo. Whereupon complaining Pliny said, sometimes double barked trees have to protect themselves from the heat and the cold found in nature. But man does not have this protection and from birth is naked, wailing and crying in such an excellent fashion. Neither does man have any thoughts from birth. But the nanny stays close like a magnet and protects the child above all else and sympathizes with the baby, protects them from many deadly things, guides them to discover their fate, and tries to get them to avoid fighting and conflicts. Fighting leads to such brutality. But no man should arise into a place of so many evils. However, that Lucifer being deprived of the Glory immortal designs for all humans to live mediocrely and hence end up in deadly misery for a thousand years: after ones first actions it is easier to warn them of the decline that leads to the eternal and deep abyss. Wherefore, be sober and watchful in prayer: surround yourselves with the few nurturing less our adversary Satan as lion come bellowing and devour you. And some said the apostle: Do you know the height of Satan himself is transformed into an angel of light (Savonarola 1496).

From this translation, it appears that Girolamo is fighting against the Catholic Church becoming corrupted by those who have no zeal for Christianity. He is angry not only with the church but also with members of the public who were perhaps not protecting themselves against the worldliness of the time. He was strongly concerned with God’s judgement on the city of Florence for its wickedness and was passionate about the Church regenerating to Holier form (Passaro 2006). He was also extremely zealous regarding the salvation of lost souls and was obviously willing to risk his life for this task. From this sermon, he also felt that Christians and non-Christians alike needed to watch and prepare for Satan’s temptations lest they be taken and destroy for falling prey to them (Kirsch 2015).

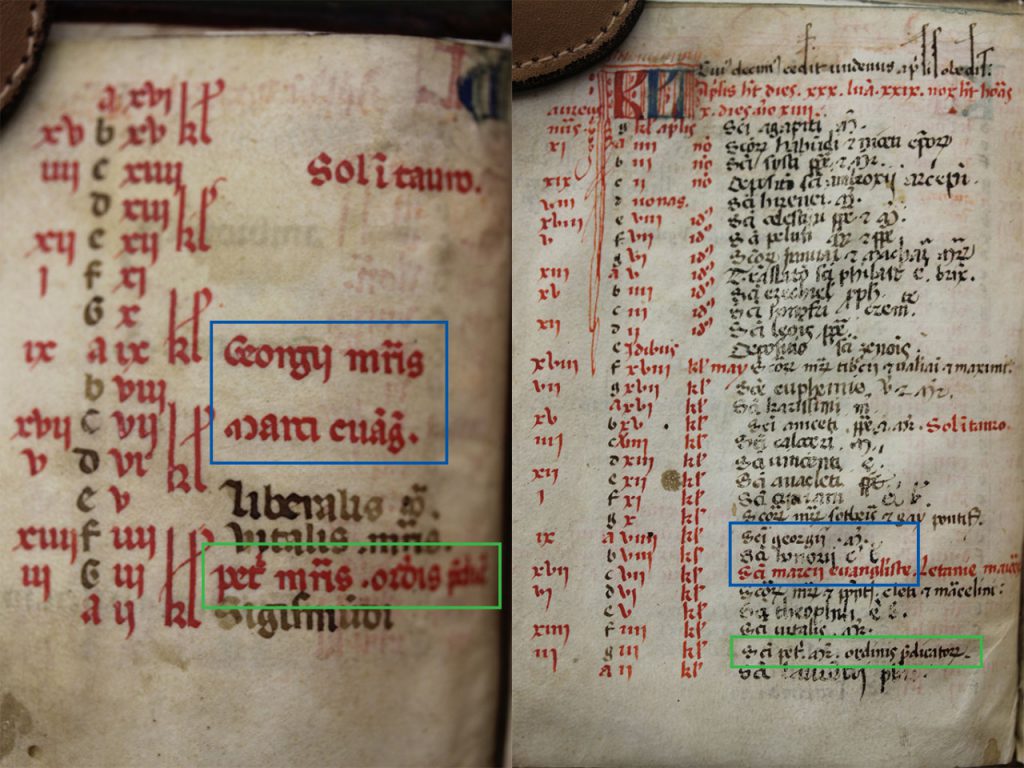

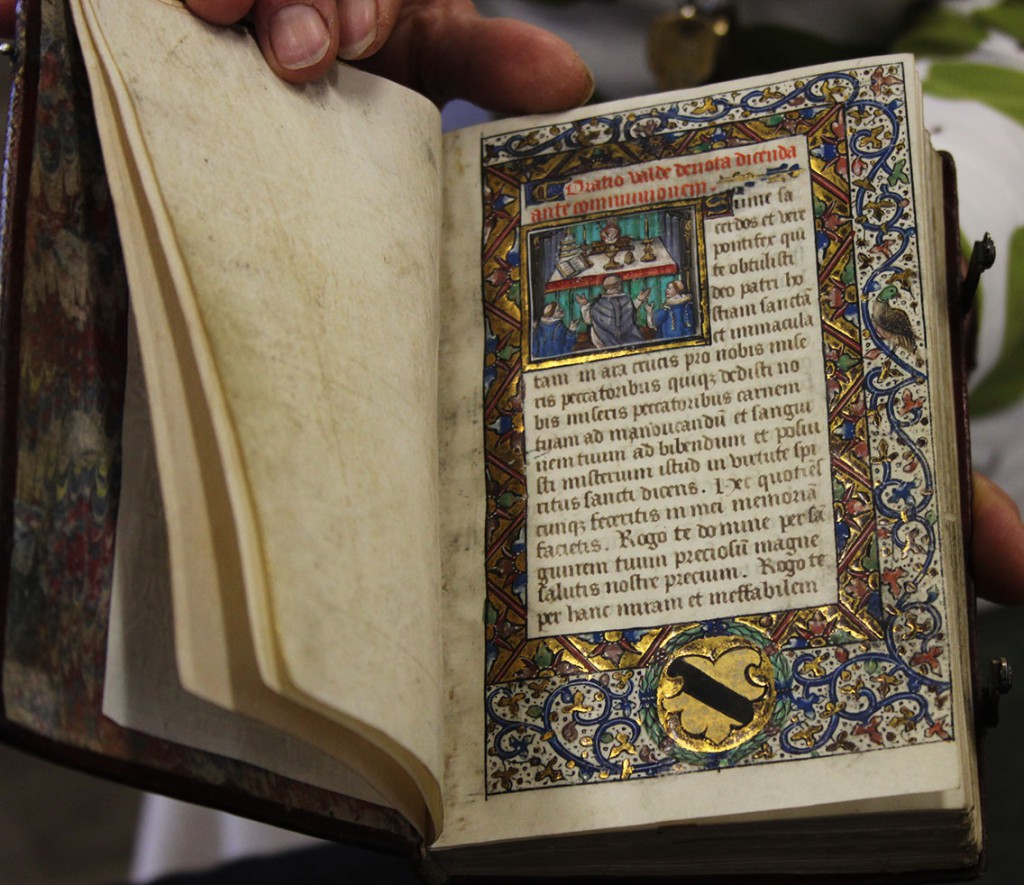

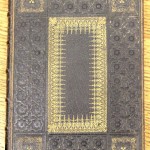

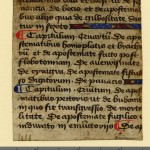

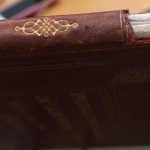

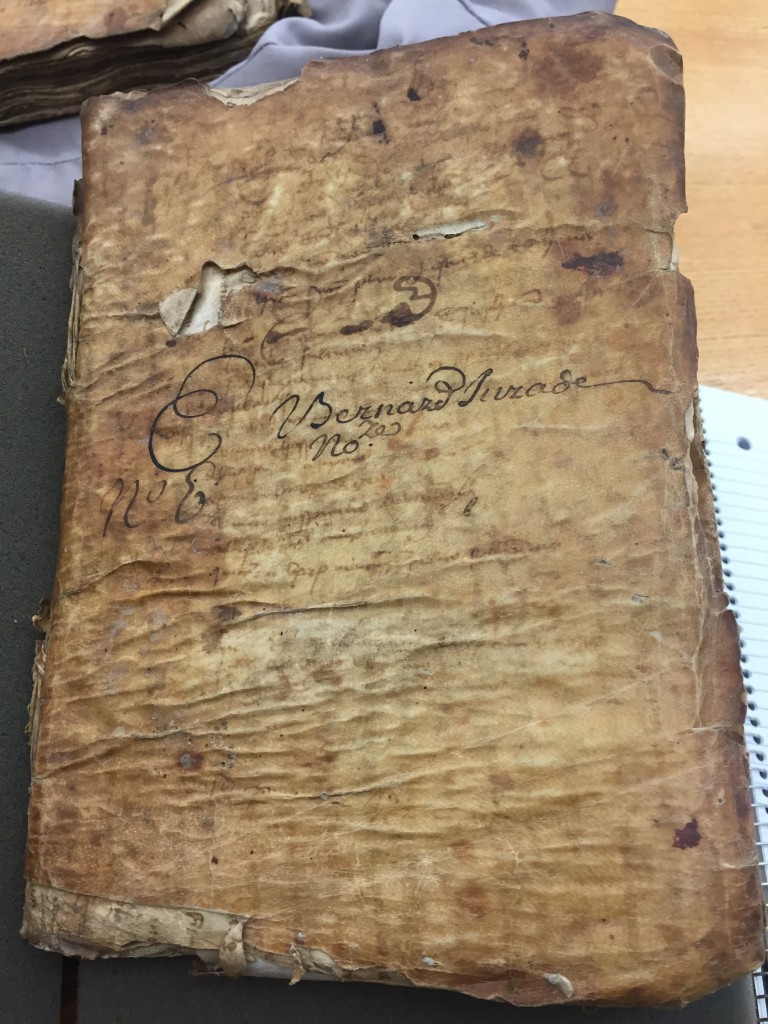

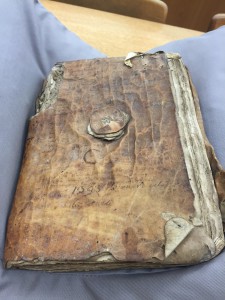

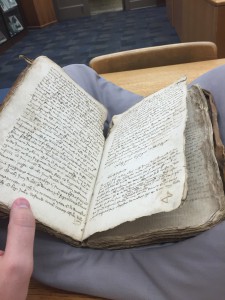

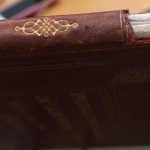

The Epistola Consolatoria De Caldi Freddi & Tiepi is bound in brown leather decorated with gold leaf of which Dr. Barabtarlo spoke about during her lectures. The inside cover has a red flowered, stamp design that is simple and beautiful. The book was used often as seen by the external binding being rather beat up on the edges and the internal markings from users’ fingers. One of the original pages is torn out and has been replaced by a printed copy of the original page. There are no comments from anyone besides librarians. There are a total of twelve printed pages with seven of those being Girolamo’s sermon and the other four being a frottola, Italian secular song popular in the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

The Epistola Consolatoria De Caldi Freddi & Tiepi is bound in brown leather decorated with gold leaf of which Dr. Barabtarlo spoke about during her lectures. The inside cover has a red flowered, stamp design that is simple and beautiful. The book was used often as seen by the external binding being rather beat up on the edges and the internal markings from users’ fingers. One of the original pages is torn out and has been replaced by a printed copy of the original page. There are no comments from anyone besides librarians. There are a total of twelve printed pages with seven of those being Girolamo’s sermon and the other four being a frottola, Italian secular song popular in the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

There were only approximately fifteen printers in Florence during the decade of 1490 with only four of these printing prolifically (University of Minnesota n.d.). The epistola by Girolamo was printed by one of these, namely the firm of Lorenzo di Morgiani and Giovanni di Piero di Maganza (Johannes Petri of Mentz). In 1495, Morgiani and Petri were working for Pacini, who commissioned what is said to be the greatest Florentine illustrated book of the century (Hoyt 1939). The epistola referenced here was not of this luxurious quality however. It is more likely that it was used to spread Girolamo’s preaching to the middle class citizens of Florence.

At the start of Girolamo’s career he was full of zealous desire for the renewal of religious life in Italy. His strong preaching and teachings led him to offend many powerful people including the pope. He was an extremely notable religious leader during the pre-Reformations era, and this can be seen through his printed documents such as the one analyzed here.

Bibliography

Amelung, Dr. Peter. 2015. BRILL. November 2. http://www.brill.com/girolamo-savonarola-religious-and-political-reformer.

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. . 2015. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. November 2. http://www.britannica.com/biography/Girolamo-Savonarola.

Hoyt, Anna C. 1939. "BULLETIN OF’ THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS ." VOLUME XXXVII , August : 62.

Kirsch, Johann Peter. 2015. Girolamo Savonarola. November 3. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13490a.htm.

Passaro, Anne Borelli and Maria Pastore. 2006. Selected Writings of Girolamo Savonarola. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Savonarola, Girolamo. 1496. Epistola consolatoria de caldi, freddi, & tiepidi & una frottola insieme. Florence: Lorenzo Morgiani and Johann Petri.

University of Minnesota. n.d. "Portfolio Artistic Monographs, Issue 12." 54-55. Seeley and Co., 1894.

What are your plans after graduation?

What are your plans after graduation?