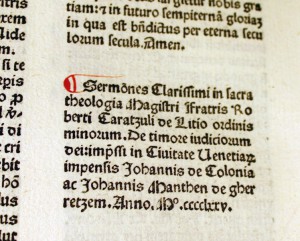

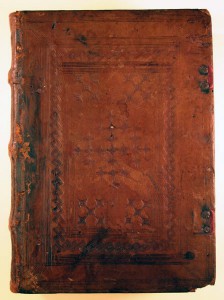

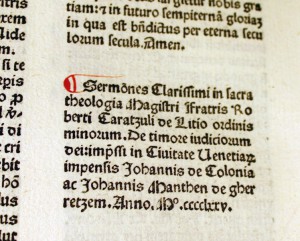

The Special Collections and Rare Book department recently acquired four incunables,[1] and we’ll be featuring them individually on the blog. This post highlights Sermones de adventu by Roberto Caracciolo (Venice, 1474), a book interesting for what it can tell us about religion and technology.

Renaissance Preachers

The author of this book, Fra Roberto Caracciolo de Lecce, was one of the most successful preachers of the fifteenth century, hailed as a “second St. Paul” for his oratorical talents.

The author of this book, Fra Roberto Caracciolo de Lecce, was one of the most successful preachers of the fifteenth century, hailed as a “second St. Paul” for his oratorical talents.

As a preacher, Caracciolo’s crowd-pleasing specialties were melodrama and spectacle; he even boasted that he could reduce any audience to tears. His career started early. By 1450, when he was only in his mid-twenties, he was well-known enough to be chosen by Pope Nicholas V to deliver the official canonization eulogies for Bernardino of Siena. Later in his career, when asked to preach a crusade sermon against the Ottoman Turks, he did so in full knight’s armor, complete with a sword. It’s no wonder that large, enthusiastic crowds flocked to hear him wherever he went.

Eager to capitalize on the popularity of Caracciolo and his colleagues, printers issued vo lumes of their sermons in Latin and vernacular Italian. Caracciolo alone had at least eight different editions of his sermons printed throughout Italy from the 1470s until his death in 1495. By the time the sixteenth century drew to a close, over one hundred editions of his works had been printed throughout Europe.

lumes of their sermons in Latin and vernacular Italian. Caracciolo alone had at least eight different editions of his sermons printed throughout Italy from the 1470s until his death in 1495. By the time the sixteenth century drew to a close, over one hundred editions of his works had been printed throughout Europe.

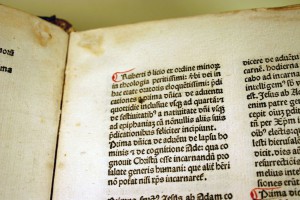

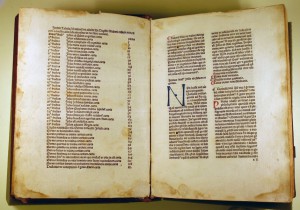

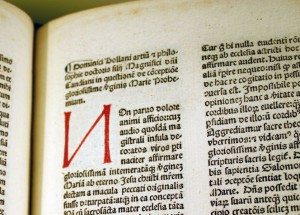

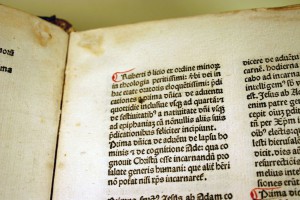

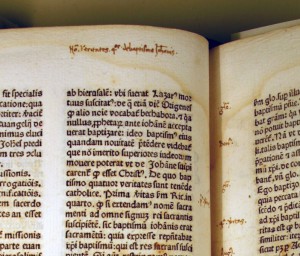

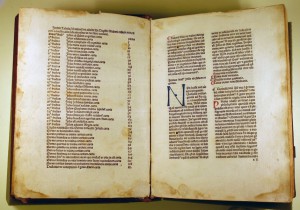

This volume contains Caracciolo’s sermons on Advent, St. Joseph, the Beatitudes, divine charity, and the immortal soul, as well as a sermon by the canon lawyer Dominicus Bollanus on the immaculate conception of the Virgin Mary. It preserves the words Caracciolo’s audiences heard and read so that we can access them today. Thanks to this copy’s scattered marginal notes in sixteenth-century handwriting, we can even know how they responded.

The Fifteenth-Century Tech Boom

As Caracciolo’s career as a preacher reached its height, Italy stood on the brink of a technological revolution. Gutenberg had developed movable type in Mainz around 1455, but it took about a decade for the technology to reach Italy. Venice had to wait even longer – until 1469. That’s the year that Johannes of Speyer emigrated from Mainz, got a five-year monopoly from the Doge, and set up shop as the city’s first printer.

As Caracciolo’s career as a preacher reached its height, Italy stood on the brink of a technological revolution. Gutenberg had developed movable type in Mainz around 1455, but it took about a decade for the technology to reach Italy. Venice had to wait even longer – until 1469. That’s the year that Johannes of Speyer emigrated from Mainz, got a five-year monopoly from the Doge, and set up shop as the city’s first printer.

Unfortunately for the Speyers, Johannes died around eighteen months later, invalidating the monopoly. His brother Vindelinus attempted to carry on the business, but Johannes’ death touched off an equivalent of the dot-com boom of the late 1990s. Within three years, there were at least a dozen printing shops in Venice, all producing the same Greek and Roman texts – over 80 different editions of them by the end of 1472. By 1473, the book market was so glutted with classics that the bottom dropped out.

This was merely the first in a series of market collapses, but most of Venice’s new high-tech start-ups went out of business as a result. The Speyer press survived – barely. Vindelinus sold a large stake in the company to two new investors: Johannes de Colonia (also called Johannes of Köln or Cologne), and Johannes Ma nthen de Gerresheim. Colonia and Manthen became the senior partners in the business; Vindelinus’ name disappeared from the company until 1476.

nthen de Gerresheim. Colonia and Manthen became the senior partners in the business; Vindelinus’ name disappeared from the company until 1476.

Colonia and Manthen were prolific printers, producing 86 editions from 1474 to 1480. They gave up on the Greek and Roman classics after 1475 and shifted their focus to the more profitable market in law, theology, and philosophy. This book is an example of the output from their reinvented company, produced during their first year of business.

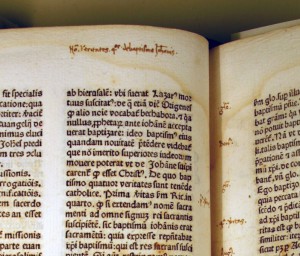

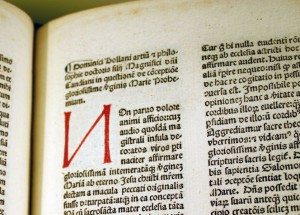

Although the Speyer brothers are sometimes credited as the originators of Roman type, this book was printed using their space-saving but  elegant Gothic. Like many other early printed books, the printers left space for initials and ornament to be added by hand. In this copy, several of the initial Ns are written backwards, for what reason we do not know.

elegant Gothic. Like many other early printed books, the printers left space for initials and ornament to be added by hand. In this copy, several of the initial Ns are written backwards, for what reason we do not know.

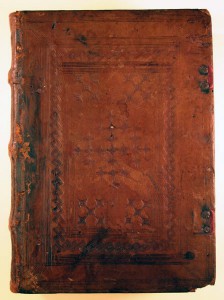

There’s much more this book could tell us; a book is never just a book when it’s in Special Collections. As its own history shows, this particular book has been an active participant in a tradition of study that has continued for hundreds of years.

Want to Read More?

The following resources are available at MU Libraries.

Aguzzi-Barbagli, Danilo. “Roberto Caracciolo of Lecce,c. 1425-6 May 1495.” In Contemporaries of Erasmus: a biographical register of the Renaissance and Reformation. Ed. Peter G. Bietenholz, Thomas B. Deutscher, associate editor. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, c1985.

Aguzzi-Barbagli, Danilo. “Roberto Caracciolo of Lecce,c. 1425-6 May 1495.” In Contemporaries of Erasmus: a biographical register of the Renaissance and Reformation. Ed. Peter G. Bietenholz, Thomas B. Deutscher, associate editor. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, c1985.

Gerulaitis, Leonardas Vytautas. Printing and Publishing in Fifteenth-Century Venice. Chicago: American Library Association, 1976.

Telle, Emile V. “En marge de l’éloquence sacreé aux XVe-XVIe siècles: Erasme et Fra Roberto Caracciolo.” Bibliothèque d’humanisme et Renaissance. Travaux et Documents 43 (1981): 449-470.

[1] The word incunabulum (plural incunabula, or incunable(s), if you prefer English) means in the cradle in Latin. It is generally applied to printed books produced prior to 1501, in the earliest years of printing.

The author of this book, Fra Roberto Caracciolo de Lecce, was one of the most successful preachers of the fifteenth century, hailed as a “second St. Paul” for his oratorical talents.

The author of this book, Fra Roberto Caracciolo de Lecce, was one of the most successful preachers of the fifteenth century, hailed as a “second St. Paul” for his oratorical talents.

lumes of their sermons in Latin and vernacular Italian. Caracciolo alone had at least eight different editions of his sermons printed throughout Italy from the 1470s until his death in 1495. By the time the sixteenth century drew to a close, over one hundred editions of his works had been printed throughout Europe.

lumes of their sermons in Latin and vernacular Italian. Caracciolo alone had at least eight different editions of his sermons printed throughout Italy from the 1470s until his death in 1495. By the time the sixteenth century drew to a close, over one hundred editions of his works had been printed throughout Europe.

As Caracciolo’s career as a preacher reached its height, Italy stood on the brink of a technological revolution. Gutenberg had developed movable type in Mainz around 1455, but it took about a decade for the technology to reach Italy. Venice had to wait even longer – until 1469. That’s the year that Johannes of Speyer emigrated from Mainz, got a five-year monopoly from the Doge, and set up shop as the city’s first printer.

As Caracciolo’s career as a preacher reached its height, Italy stood on the brink of a technological revolution. Gutenberg had developed movable type in Mainz around 1455, but it took about a decade for the technology to reach Italy. Venice had to wait even longer – until 1469. That’s the year that Johannes of Speyer emigrated from Mainz, got a five-year monopoly from the Doge, and set up shop as the city’s first printer.

nthen de Gerresheim. Colonia and Manthen became the senior partners in the business; Vindelinus’ name disappeared from the company until 1476.

nthen de Gerresheim. Colonia and Manthen became the senior partners in the business; Vindelinus’ name disappeared from the company until 1476.

elegant Gothic. Like many other early printed books, the printers left space for initials and ornament to be added by hand. In this copy, several of the initial Ns are written backwards, for what reason we do not know.

elegant Gothic. Like many other early printed books, the printers left space for initials and ornament to be added by hand. In this copy, several of the initial Ns are written backwards, for what reason we do not know.

Aguzzi-Barbagli, Danilo. “Roberto Caracciolo of Lecce,c. 1425-6 May 1495.” In

Aguzzi-Barbagli, Danilo. “Roberto Caracciolo of Lecce,c. 1425-6 May 1495.” In