This post is the seventh part of our continuing series on Dr. Juliette Paul's English 4300 class and their research on an early American manuscript in Special Collections.

by Tyler Morris

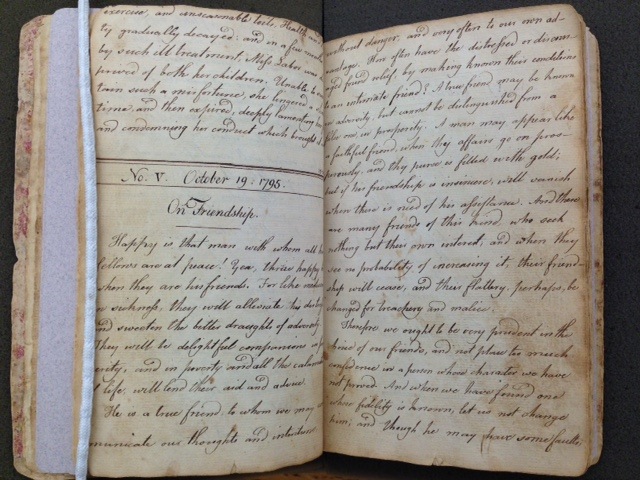

After weeks of working to decode The Lucubrator, I can’t help but feel I’m left with more questions than answers. The title page offered our class a name: James Noyes. But we quickly realized that the manuscript’s authorship is more of a mystery than any of us originally thought. Simply searching for “James Noyes” in databases and Google was not going to cut it. So I altered my approach. I looked to find “Lucubrator” essays written by other authors who could potentially eliminate James Noyes as a candidate for the authorship of some or all of The Lucubrator’s essays.

Though I found a few published essays written by “The Lucubrator,” none matched those bound in the manuscript. We concluded that we could not attribute the manuscript to Noyes definitely nor question the attribution made on the title page. Eventually, I posed a different question: what good is a book that no longer has a known author or place of origin?

When considering my answer, it dawned on me that I had learned more from the manuscript than I originally thought, even without knowing its author. The fact that we could not find a printed version of a Lucubrator essay suggests either that someone should have done a better job of bookkeeping or that the manuscript may not have been meant for the public. But, then again, I think my speculation that the manuscript’s essays were at one time printed to entertain and inform readers is a compelling one, for several reasons.

Some of the essays are not dated in chronological order and others are given two dates, which may signify the dates on which they were printed elsewhere. Moreover, the essays are morally edifying. My favorite essay is one entitled “On Friendship.” After overcoming the difficulty of having to read literature in the original handwriting, you find that the author of The Lucubrator actually offers a rather beautiful description of true friendship. Phrases like “Friendship, when it is sincere, is acknowledged by all to be a very fruitful source of happiness,” or “When there is a dissimilarity of opinions or pursuits, there seldom exist any great degree of friendship; for that difference is apt to create disputes between each other, and people in general are too much attached to their own ways of thinking to respect another of different or opposite sentiments,” offer some insight and advice that is still very useful today. The same goes for the essays that offer criticism, such as “Propriety of Behaving with Moderation In Parties,” which is pretty much self-explanatory, and “On the Propriety of Taxing Ministers of the Gospels for the Support of Government.”

Likewise, learning about the life of the best candidate for the manuscript’s authorship, James Noyes of Atkinson (1778-1799), was inspirational. Interestingly enough, Noyes was around the same age as me and my classmates when The Lucubrator was written, which made me feel like I needed to step my game up as far as everything is concerned! Noyes was a prodigy responsible for publishing a Federal Arithmetic for Congress, as well as a number of almanacs and even an astronomical diary, which are profound achievements for anyone, but especially for an author so young. A few years later, Noyes died of polio, after being forced to use crutches. Issues with immobility left him stuck in his house for most of his final days.

I think that integrating short essays like the Lucubrator essays with applications such as Twitter and Facebook would be an excellent way to entertain my generation, as well as a tool for teaching life lessons. The idea and form of The Lucubrator are what we can take away from our research experience and what we can call the manuscript’s history and purpose, even if the author conceived of it differently.