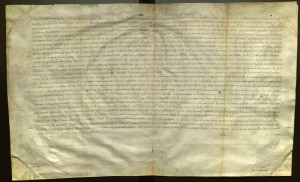

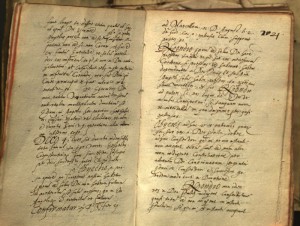

Happy Manuscript Monday! This week's offering is a letter from the papal chancery of Pope Leo X, written in Rome on March 27, 1517, to Ottaviano Fregoso, Doge of Genoa. The letter is signed Jacopo Sadoleto as papal secretary and was written by the papal scribe, Ludovico degli Arrighi. In addition to being a papal scribe, Arrighi was a type designer and author. His typefaces, based on his own elegant script, have influenced the design of fonts and letter forms from the Renaissance to the present.

Kelli Hansen

An address, delivered before the members of the Franklin Debating Club, on the morning of the 5th July, 1824

Pamphlets – literature published in an unbound, ephemeral format – are one of the strengths of Special Collections. The collections contain thousands of sermons, speeches, tracts, and political writings from the seventeenth through the nineteenth century, many of which are very scarce. We'll share a pamphlet each week to highlight these holdings.

This week's selection comes from the Fourth of July Orations Collection. It's one of eight known copies, all in the United States, and contains exactly what it says it does – the text of a Fourth of July address given in 1824.

The Fourth of July Orations collection is a great source for studying the development of American identity and politics. Many speeches, including this one, comment on contemporary world events and urge leaders to stick with the values and policies espoused by the country's founders.

Newburyport, [Mass.] : Printed at the Herald office [by Ephraim W. Allen], 1824. Find it in the MERLIN catalog.

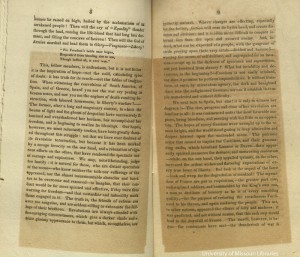

A ninth-century fragment of De orthographia by Bede

This semester, we're kicking off a new series. Every Monday, we'll share a page or two from the department's manuscript holdings – just enough to give you a glimpse into the collections.

First up: the oldest manuscript in the collections, a fragment of De orthographia by Bede from the 9th century (Fragmenta Manuscripta #002). Fragmenta Manuscripta is a collection of leaves, clippings, and binder's waste assembled by bookseller John Bagford in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century. It's fully digitized – find out more about it at Digital Scriptorium.

Stay tuned next Monday for another manuscript from the collections.

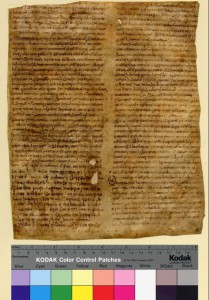

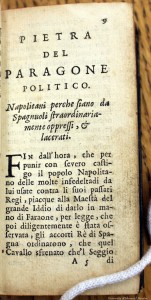

Pietra del paragone politico

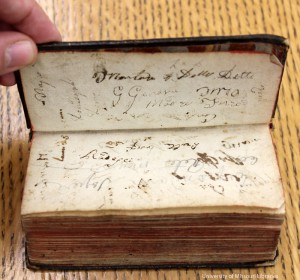

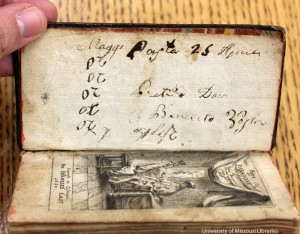

This is Pietra del paragone politico by Trajano Boccalini (1556-1613), an Italian political satirist whose writings were influential during the late Renaissance. Boccalini died before the publication of this work, which is a scathing attach on the Spanish for the treatment of their subjects during their occupation of the Kingdom of Naples.

Like many works that challenged authority, this one was issued with a false imprint for the protection of its printer. It has a beautiful engraved title page featuring a king talking with a courtier. It's small – just the right size to be concealed in a pocket. And, interesting for us (or for this librarian, at least), the endleaves are covered with pen trials. Find it in the MERLIN catalog, and come by to see it in person.

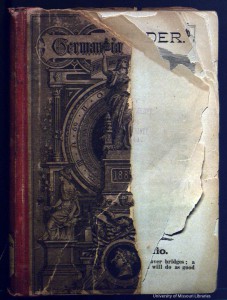

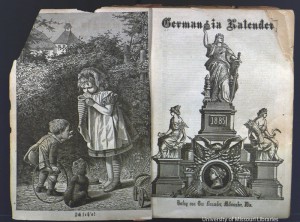

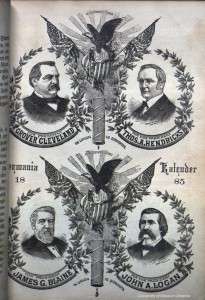

Germania Kalender and the Academic Hall Fire of 1892

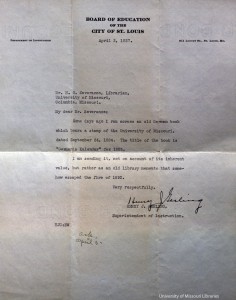

Academic Hall burned 122 years ago today, leaving the Columns to become a Mizzou icon. Before the fire, the building housed classrooms, offices, libraries, and museums – almost the entire university. Although parts of the Law Library were salvaged, the main library was a total loss. Almost.

Germania Kalender survived because it was checked out during the fire. However, it wasn't returned to the University until 1937, forty-five years later. After it came back, it was placed in the Rare Book Room. It's in rough condition – who knows what it went through over at least 45 years of being checked out? – but it's been here ever since.

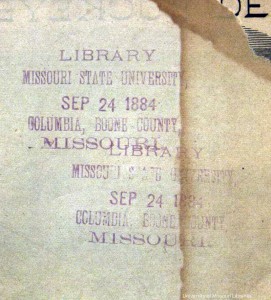

The book was returned by Henry Gerling of St. Louis. The date, September 24, 1884, and the library stamp for Missouri State University (which was one of the names used by the University of Missouri at the time) alerted him to the book's history.

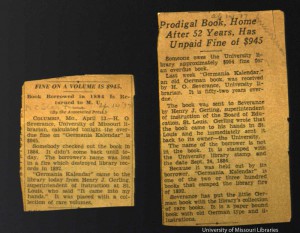

When the book was returned, the story made the news. These are clippings from the Kansas City Star (left) and the Columbia Missourian (right) from April 14, 1937.

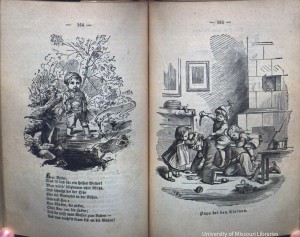

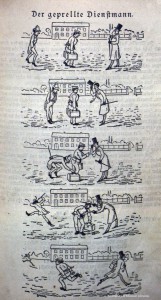

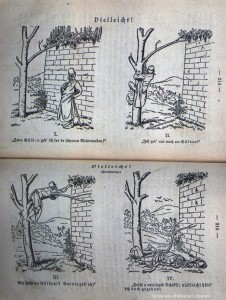

Germania Kalender has calendars and an almanac, as you'd expect from the title, but it also contains pictures and readings on various subjects for the entire family.

It even includes some early comics!

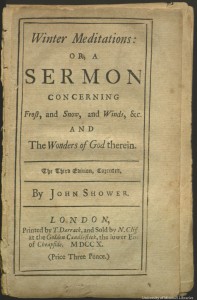

Winter meditations

Here in Columbia, we were greeted by temps of -10 (with wind chills of -25) during our morning commute. A meditation on winter somehow seems appropriate today.

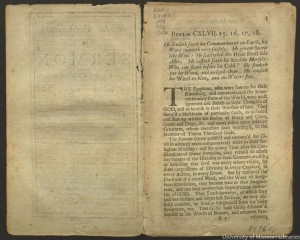

John Shower (1657-1715) was a Presbyterian minister who published several works during his lifetime, mostly funeral sermons. His Winter Meditations was first published in 1695, and was fairly popular – this is the third edition. In this sermon, Shower sets out to illustrate the ways his parishioners could see winter as a blessing.

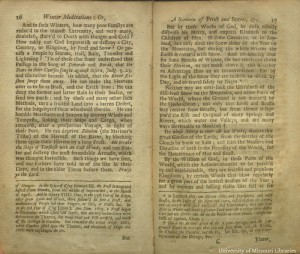

For instance, "In some Countreys, as in Lapland, not only doth the Snow abide all the Year on the Mountains, but durign the whole Winter the Earth is cover'd with Snow. And considering that for some Months of Winter, the Sun riseth not above their Horizon, or not much above it, this is rather an Advantage than an Inconvenience. For by the Light of the Snow they are enabl'd to work by Day, and to travel safely by Night."

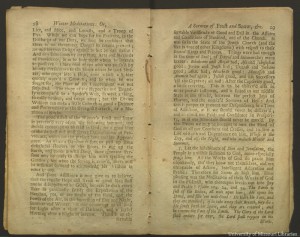

"The good Effect of the Winter's Frost and Snow is perceiv'd very often the following Summer… As when a Gardner is seen to pull up some delightful Flowers by the Roots, to dig up the Earth, and cover it with Dung, some ignorant Person may be ready to charge him with spoiling the Garden; but when Spring is arriv'd, there will be sufficient Ground to acknowledge his Wisdom in what he did."

And it could be a lot worse.

Our temperature should climb into the 20s tomorrow. Perhaps winter really isn't so bad. As Garrison Keillor put it, more than 300 years after Shower, "Winter is what we were meant for and we welcome it. We thrive on adversity and that’s just the truth. The snow shovel is the secret of happiness."

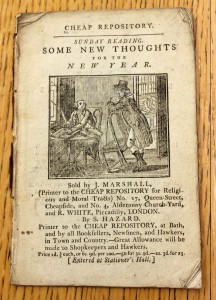

Some new thoughts for the new year

Here are some New Thoughts for your New Year, courtesy of our extensive collections of seventeenth- through nineteenth-century British pamphlets. This one was printed in 1796.

The Cheap Repository Tracts series was created by the British poet, playwright, and philanthropist Hannah More, whose writings often dealt with religious themes. They were printed in large quantities for distribution to the poor. Although there must have been thousands of original copies, they were ephemera – not meant to be preserved. Only six copies of this tract are recorded in libraries around the world.

Many of the tracts deal with people in trades or in domestic service. This one shows "How Mr. Thrifty the great Mercer succeeded in his Trade, by always examining his Books soon after Christmas, and how Mr. Careless, by neglecting this rule, let all his affairs run to ruin before he was aware of it." The pamphlet ends with a hymn for the new year.

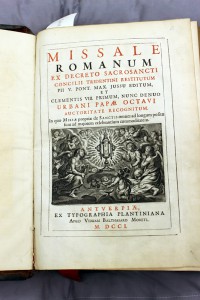

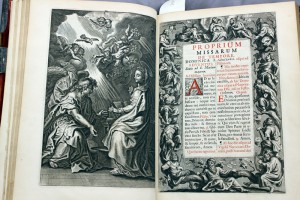

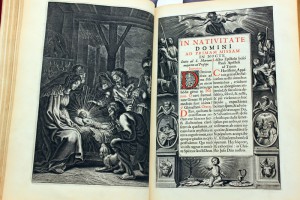

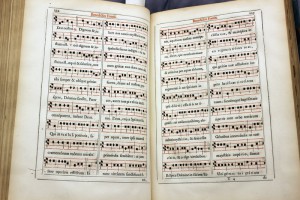

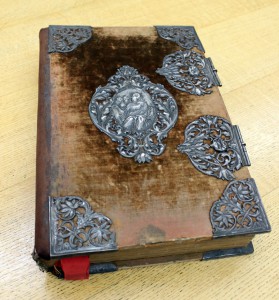

Missale Romanum, 1701

We're always making new discoveries in Special Collections, and this is one exciting find. This Roman missal was published by the Plantin-Moretus Press in 1701. It's bound in red velvet with silver clasps and decorations, gilt edges, leather tabs, and red silk bookmarks. The text is printed throughout in red and black, and there are amazing engravings after works by Rubens. Interestingly, the name of a previous owner is engraved on one of the clasps: "HAC Defresne Possessor – 1817."

There are six copies in WorldCat. Three, including ours, are in North America (two in the United States, and one in Canada). The others are in the Netherlands.

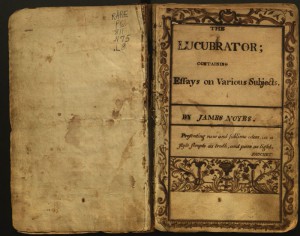

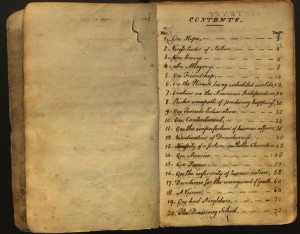

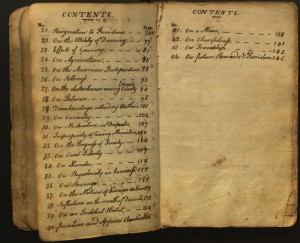

Unsolved Mystery #6: The Lucubrator by James Noyes

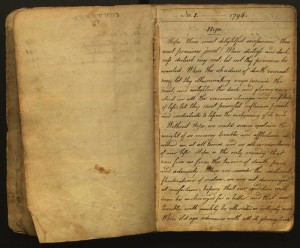

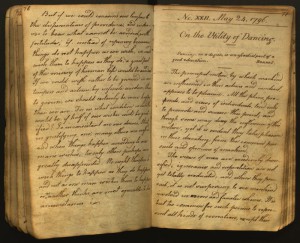

Our final unsolved mystery of the semester is a manuscript donated to the MU Libraries by Mrs. Edwin Ball in 1974. Its title page attributes the work to James Noyes, but we know very little else about it. It consists of a series of essays on a wide variety of topics. Titles include "On Female Education," "On Bad Neighbors," and "On the Utility of Dancing," to name a few. The essays are dated between 1794 and 1797. James Noyes (1778-1799) wrote a mathematics textbook and a couple of almanacks around 1793-1794, but we have not been able to establish whether he and the author of this manuscript are one and the same.

Who was James Noyes? Is this manuscript in his hand? Where was it created? Were the essays ever published?

As always, email us at SpecialCollections@missouri.edu with your thoughts on this unsolved mystery.

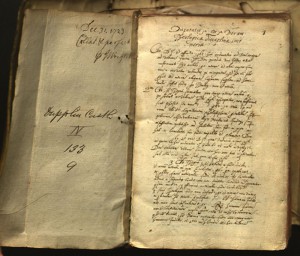

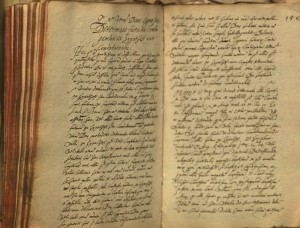

Unsolved Mystery #5: Latin Manuscript

This manuscript came to us as a part of a larger acquisition made in 2006. The text is unidentified, although we think it may have something to do with the writings of Thomas Aquinas. The front flyleaves contain a library shelfmark for Dupplin Castle, and the inscription "collat. & perfect. p. J. Wright," dated December 31, 1723. Stephen Ferguson at Rare Book Collections @ Princeton has a very informative blog post about J. Wright and the books he collated as librarian for the Earl of Kinnoull.

Can you identify the text? When was it produced, and by whom?

Email us at SpecialCollections@missouri.edu with any information.