To read more about King Tut, the discovery of his tomb, and the Grand Egyptian Museum, please check out the library’s November 5, 2022, copy of New Scientist and the November 2022 issue of National Geographic both available in the current journals/periodicals section on the 1st floor of Ellis Library.

Amongst the myriad of anniversaries around the world, there is a 100 year anniversary you may not be aware of: the discovery of the tomb of King Tutankhamun. While this was an invaluable discovery, the mysteries surrounding the tomb and those who found it continue today.

Most of us learned about King Tut in school, yet little has been written about the boy king, who died in his late teens. Instead, it’s the artifacts found within the tomb that have led to the discovery of many aspects of his life. Much of Egypt’s past was brought to life through King Tut’s burial, including clues about trade routes around the Nile, the incredible wealth of Egypt’s 18th dynasty, and how kings were buried in Egypt.

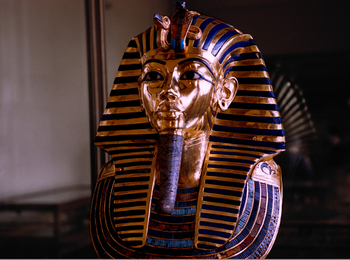

This last discovery was a surprise to many, who were unaware of the extravagant burial traditions of the Egyptians. Tutankhamun was buried with a mask made of gold, glass, and semi-precious stones. Life-size statues guarded his burial chamber. These were vessels designed to allow the pharaoh’s ka, or life force, to inhabit them in the afterlife. More than 200 pieces of jewelry were found, along with golden beds, chariots, a golden throne, and a massive sarcophagus containing three nesting coffins, all showing King Tut with the curving beard we’ve seen in pictures, in the likeness of Osiris, the god of the dead. Guardians wrap the coffins in their protective wings, and the mummy itself was found in the innermost coffin, made of 243 pounds of solid gold. Though over 5,400 objects were found throughout four separate rooms, King Tut’s tomb was considered small by most standards, but was filled with everything you would typically see in this society, who wished him to have whatever he needed to live like a king for all eternity.

Simply cataloging and discussing the artifacts in the tomb could (and have) filled books, but what has fascinated people throughout the years are the mysteries surrounding the tomb.

The first is the “Curse of the Pharaohs,” which is allegedly cast on anyone who disturbs the mummy of an ancient Egyptian. Though there have been tales of curses going back to the 19th century, but after the tomb of King Tut was opened, the stories multiplied based on the misfortune of several members of the excavation team. The number of people who visited the tomb, as well as the number of people who died suspiciously, varies, but the most famous is that of Lord Carnarvon, the sponsor of the dig, who died five months after the discovery of an infected mosquito bite. One man died of pneumonia in 1923, another died soon after x-raying the mummy in London, another died by suicide in 1924, and Carter’s personal secretary died in 1929. Another man was allegedly given a gift from the tomb and his house burned down shortly after. Other deaths have been attributed to the “curse,” but one who thought it was all ridiculous was Howard Carter, the man who led the dig. Carter died of cancer 17 years after the excavation and never believed in the curse, but the lore surrounding it has continued, with some thinking that a specific mold or bacteria could have led to some deaths, leading doctors to conduct actual studies regarding the statistics of deaths and illnesses vs those who were just fine, and have found no correlation between the tomb and the misfortune of those unlucky few. But everyone likes a good story, and the curse story has only grown, prompting the creation of several books and movies.

A second mystery concerns a dagger found in the tomb. When examining the bindings of the mummy, Carter found a dagger that seemed out of place. The sheath was gold, as was common, but the blade was iron, a metal that was smelted in Egypt until centuries after Tutankhamun’s death. How did it end up there? For years, people assumed the dagger was imported from some far away place, or perhaps gifted by a diplomat from a foreign country. However, we now have the technology to study the dagger. In 2016, it was confirmed that the iron originated from much further away than previously thought, and contained high levels of nickel associated with meteoric iron, meaning that to the Egyptians who wrapped it close to the pharaoh’s body, it was a gift from the gods. While this discovery is significant, more important is the fact that in the current study of archaeological finds, the mummy would not have been unwrapped to pull the dagger out and catalog it – instead, scientists can now use x-rays and CT scanners to create 3D images of what is contained inside the mummy, even 3D printing replicas of the internal structure. King Tut’s mummy was scheduled to go on an international touring exhibition in 2010, but was deemed to fragile, so the curators were able to print a realistic replica of the pharaoh.

The final mystery is one that has been studied since the tomb was found – how did the young king die? Often depicted with a staff, many have thought that King Tut had scoliosis and/or a club foot. In 1968, Tut was x-rayed for a documentary and was found to have evidence of a blow to the head, leading to multiple murder theories, but it turns out that the scan was simply showing something that wasn’t really there. In 2005, a CT scan showed that the pharaoh’s left femur was broken, leading to the theory that he fell in a chariot accident, but others have argued that the CT scans cannot distinguish between a pre-mortem and post-mortem injury. In 2010, there an attempt to extract DNA from the bones and reported that the king had malaria, his parents were siblings, and he had a club foot, which paints the king as inbred and infirm, but this DNA discovery has been challenged as well – extracting DNA from a mummy’s bones isn’t an exact science, and contamination is a real concern based on how much the mummy has been through over the years. Other recent speculations include the idea that Tutankhamun had epilepsy or was killed by a hippo. Though technology is helpful, there is still much speculation regarding King Tutankhamun.

So the world has speculated and argued over the pharaoh and his cause of death, opened his tomb and extracted the treasures inside, and even taken him on trips around the world. This is perhaps not what the Egyptians would have liked when we think of the burial he received, but we can start to show more respect now: using CT scans rather than simply pulling out treasures and undoing the bandaging process; the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum, where many of the objects from the tomb will be displayed for the first time, and in the rightful country of ownership; and learning that, despite all the wealth in that tomb, the king may have led a very short life without much happiness, that before he became the famous King Tutankhamen, he was born Tutankhaten (living image of Atun), had to ascend to the throne at only 8 or 9-years-old after his radical father died, was pressured to return to the old ways of of the Egyptian gods and even changing his name to “Tutankhamen,” (living image of Amun), wed to a woman who was likely his half sister, died suddenly, and was sadly buried with his two stillborn daughters. More than anything, his legacy lives on in the way it changed the work of archaeologists, made scientists use technology in new, more careful ways; and introduced a world to Egyptology and a culture that many would have never discovered.

Other resources for this writing include:

“King Tut Tomb Curse”

“Ten Things to Know About the Discovery of King Tut’s Tomb”

“The Mummy’s Curse: Historical Cohort Study”

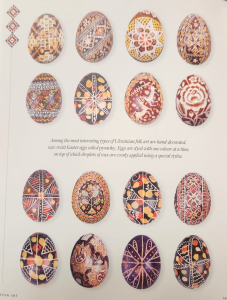

credibly detailed. This tradition dates back to pre-Christian spring rites.

credibly detailed. This tradition dates back to pre-Christian spring rites.