Today I learned: Benjamin Franklin believed in and researched merpeople

Ellis Library gets a lot of serials. A LOT. If you have an interest in a topic, we have at least one journal/magazine that will interest you, from art to history to footwear. Today’s focus is on History Today, “Britain’s best-loved serious history magazine.” Not a history buff? Trust me, you’ll still find something amazing in this journal or on their website (https://www.historytoday.com/) – they even included a spotify list to go with the most recent issue!

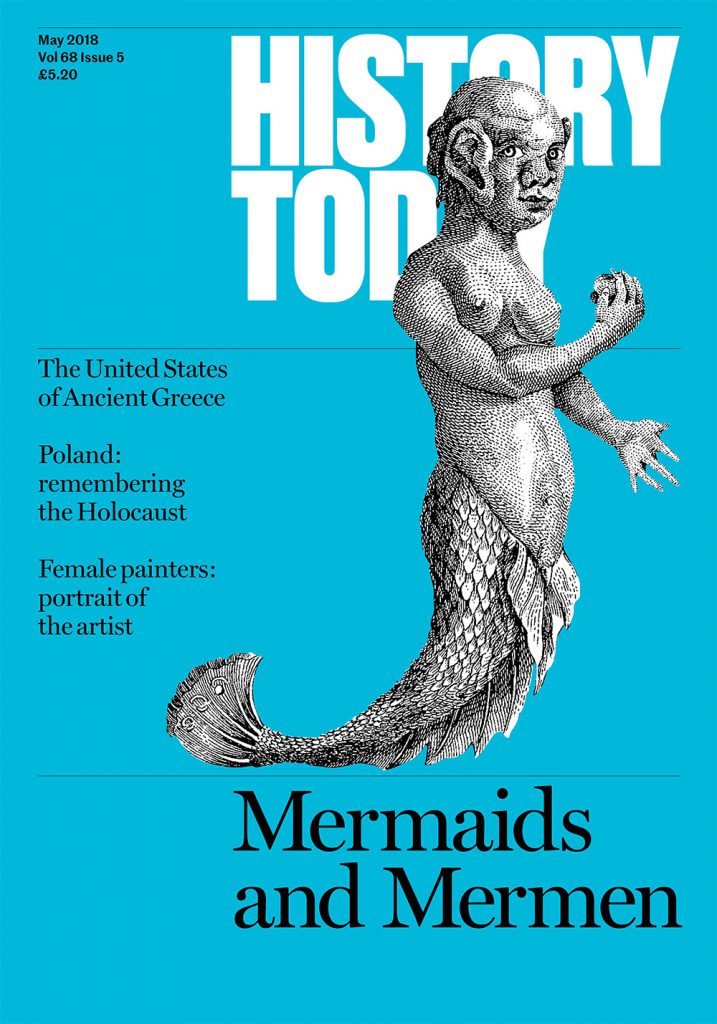

The May 2018 edition has a very creepy merperson on the cover, but don’t let that dissuade you. The article, “Diving into Mysterious Waters,” discusses not only the legend of mermaids/mermen, but how some of the most famous and intelligent people in early Europe wholeheartedly agreed that merpeople existed.

You may remember Cotton Mather from history lessons. He was the guy with giant, white hair who was disgustingly enthusiastic about hanging witches during the Salem Witch Trials. Considering he believed that nonsense, it isn’t a huge surprise that in 1716, he wrote a letter to the Royal Society in London, revealing that he sincerely believed in merpeople.

While we scoff at this admission now, was it really that surprising? Sure, Christopher Columbus believed in merpeople, even claiming to have seen three of them upon arriving in the New World, but when Europeans first landed in North America and saw the opossum for the first time, they compared them centaurs and gorgons because they had never seen a marsupial, let alone one with a grumpy face. There were new discoveries all the time. “The 18th century was as much a time of wonder as it as of rational science: the two, in fact, seemed to interweave by the day.”

It’s not surprising that tales of merpeople existed then, and still exist to this day. Since ancient times, people have worshipped merpeople. Medieval European churches were covered with mermaid symbolism (the theory is that these decorations were a reminder to Christians “of the dangers of the lust for flesh”). Even after religious changes in Europe, when Catholic imagery was erased, merpeople stuck around.

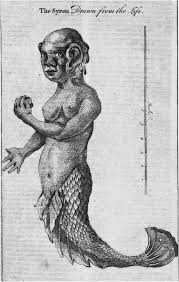

Sightings abounded as well. In 1403, a group of Dutch women apparently found a mermaid and taught her how to wear clothes, take up spinning, and converted her to Christianity. How a woman who was half fish would wear clothes or exist outside of water is beyond me, but people believed them. Mermaid sightings increased in the 16th and 17th centuries, with the seas abounding with tales of mermaids and their siren calls. The explorer Henry Hudson (of Hudson River fame) noted sightings in his captain’s log. Descriptions of mermaids over time contained the same basic information regarding their looks, until 1759, when the creepy drawing, “The Syren Drawn from Life” was published and freaked everyone out with its big ears, bald head, and “hideously ugly” features.

European cabinets of curiosity began to display “mermaid appendages” and by the end of the 18th century, some of the “smartest men in the western world,” including Benjamin Franklin and other members of the Royal Society, decided to take on the task of trapping and investigating merpeople. This was a step in the kind of scientific research we continue to use today. Sure, we may not chase mermaids around, but we do investigate other amazing things, with scientific discoveries happening all the time. Parallel universes and DNA codes may not sing to sailors and lure them to their death, but the current scientific research is still pretty amazing.

The creepy mermaid drawing vs how people typically imagine mermaids. That picture had to have bummed people out when it was published.

And to prove that not all merpeople conform to the same typical body type, here’s a new discovered species.

Save