This post highlights Summa Contra Gentiles by St. Thomas Aquinas published in Venice in 1480 by Nicolas Jenson, one of the most renowned printers. The book is of special importance to all with an interest in theology, history of book printing, and rare books. This is one of the four incunabula recently acquired by the Special Collections and Rare Book department.

On the warm and humid Venetian day of June 13th, 1480 the book was finally finished. Nicolas Jenson had only two months to live: he wasn’t well and felt old, tired and lonely. His children were in France: daughters Joanna, Catherine, and Barbara were young and unmarried, still living in Sommevoir with his beloved brother Alberto and his mother donna Zaneta; his son Nicolas, whose behavior worried him a lot, was in Lyon. A “most honorable tradesman, alien and printer of books”, Messer (as stated in his official will and testament), Nicolas Jenson, a very rich man, felt with some sadness that this strange place was going to be his final destination. A Frenchman, he had come here twelve years prior, when Venice was already in a long and exhausting war with the Turks, and when two years earlier the Doge Giovanni Mocenigo had made peace with Mehmed II, the famine and plague were still ravaging La Serenissima (the name of the Republic of Venice). Messer Jenson was a very successful printer; even his rivals admitted that the elegance of his Venetian Gothic type was unmatched — after all, he published a good quarter of all the books printed in Venice from his arrival in 1468 to 1480* , and Pope Sixtus IV made him Count Palatine.

Contra Gentiles was his second book published this year. By the end of July the last part of De humilitate interiori et patientia vera by Johannes Carthusiensis was to become his last printing venture. After his death his printing partner John of Cologne published a few more titles from the stock left after Jenson’s repose, under the joint name of Johannis de Colonia, Nicolai Jenson, and Sociorumque.

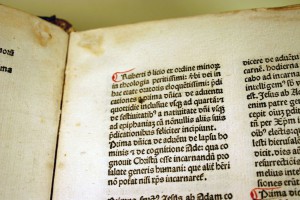

Nicolas Jenson was a master, not a scholar like Aldus, Merula, or Caracciolo, and thus he was in need of assistance by monks in proofreading the works of philosophy and especially theology. Petrus Albus Cantianus, a Dominican friar, was the editor of Contra Gentiles: at the very end of the text, after the colophon, we find his letter to Petrus Frigerius, Archbishop of Corfu (“Veneto theologico Excellentissimo Archiepiscopo Corkire[n]si ordinis”) confirming that he checked and corrected the text.

Why did Jenson decide to publish Contra Gentiles in 1480, when the market was still saturated with the books by Aquinas? Only four years earlier Contra Gentiles was brought out in Venice by Francis Renner of Heilbronn and Nicolas of Frankfurt, and before that, in September of 1475, in Rome, by Arnold Pannartz, and before him in 1473-74 Georg Reyser printed it in Strasburg. And this is not counting numerous editions of his most widely known and enormously influential Summa Theologiae.

St. Thomas Aquinas‘s authority in the Roman Church was indisputable: his works were the basis of Thomist theology and philosophy. It is widely believed that Aquinas wrote Contra Gentiles in Italy between 1261 and 1264 at the request of St. Raymond of Penafort, Magister General of the Dominican order, who wanted to have a good and convincing resource for the missionaries in Tunisia and Murcia, a Moorish kingdom in southern Spain. While written most probably in Rome, it is supposed to be based on his lectures he read at the University of Paris between 1257 and 1259. Aquinas’ intention was to give his students clear and focused answers to the most important questions about God, creation, providence and salvation. Each of the four books that constitute this work consists of about a hundred chapters (102, 101, 164, 97, to be precise). Each chapter is a question/postulate (Quod veritati fidei Christianae non contrariatur veritas rationis <That the truth of reason is not in opposition of the Christian faith>) which is then proved in a series of arguments and counter arguments, supported by citations from the Scriptures, and led to a logical conclusion.

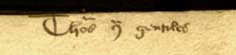

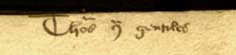

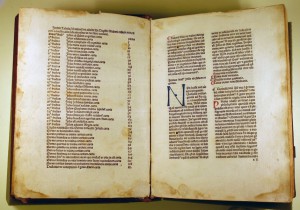

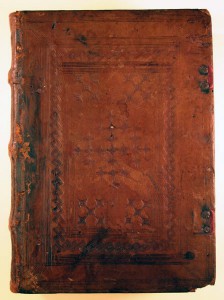

Our book looks characteristically mediaeval: in contemporary brown tooled leather binding over wooden boards with the front half of embossed metal clasps still present. The title is written in a contemporary hand on the fore-edge and at the top of the blank recto of the first printed page: Tho[mae] [contra] gentiles. The watermarks {a crown without arch between two chain-lines} suggest that Jenson bought the paper from Genf (Genève), and the binder of the book had a paper stock {watermark: Virgin Mary in a shield} produced in Dorpat (modern Tallinn) or Riga in Livonia in the 15th century.

Our book looks characteristically mediaeval: in contemporary brown tooled leather binding over wooden boards with the front half of embossed metal clasps still present. The title is written in a contemporary hand on the fore-edge and at the top of the blank recto of the first printed page: Tho[mae] [contra] gentiles. The watermarks {a crown without arch between two chain-lines} suggest that Jenson bought the paper from Genf (Genève), and the binder of the book had a paper stock {watermark: Virgin Mary in a shield} produced in Dorpat (modern Tallinn) or Riga in Livonia in the 15th century.

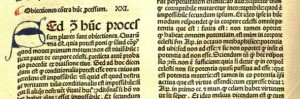

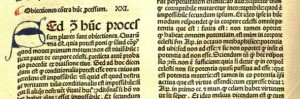

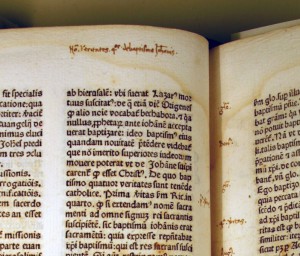

Jenson’s division of chapters differs from some of the known printed editions. He thought, for instance, that chapter 20 (Quod Deus non est corpus) was too long and he divided it after the 11th argument thus making an additional chapter 21, “Obiectiones co[n]tra hu[n]c processum”. (Objections against this reasoning). On the other hand, his Book Three consists only of 163 chapters instead of 164 in several other editions. The very first line of Chapter 20 also differs from the majority of modern texts and coincides with the Roman edition of 1894 that reads: “Ex praedictis a[u]t[em] oste[n]ditur,[ quod] Deus non e[st] corp[us]”; in later editions it reads: “Ex praemissis etiam” etc. St. Thomas’ hand was notoriously difficult to read, and it is not my task here to determine what manuscript was used by Jenson for his publication, but it is interesting to observe that even after seven hundred years of studying the text even at the beginning of the twentieth century, some passages were still being disputed, and monks who spent their entire lives reading, editing and publishing it, complained about difficulties in decoding it.

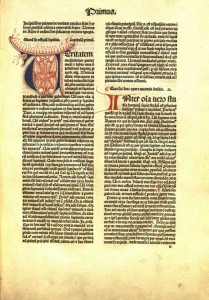

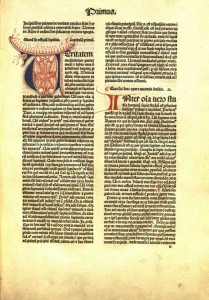

The text is rubricated with red and blue capitals. A large and very elaborate first capital “v” in “Veritatem” opens the book, and each objection and counter argument is marked with red paragraph mark up to Book Four, chapter 11; after that, hand written capital letters at the beginning of chapters continue, but paragraph marks are much rarer and frequently coincide with short contemporary notes in the text, as if a reader was rubricating while reading.

The text is rubricated with red and blue capitals. A large and very elaborate first capital “v” in “Veritatem” opens the book, and each objection and counter argument is marked with red paragraph mark up to Book Four, chapter 11; after that, hand written capital letters at the beginning of chapters continue, but paragraph marks are much rarer and frequently coincide with short contemporary notes in the text, as if a reader was rubricating while reading.

More than just another remarkable example of an incunabulum printed by one of the greatest printers of Venice, our book carries a fitting St. Thomas’ message not only to Jenson and his contemporaries, but to the posterity — and thus to us — as well, namely that “of all human pursuits, the pursuit of wisdom is the more perfect, the more sublime, the more useful, and the more joyful.” (Book 1, Ch. 2)

*There were 596 books brought out in Venice in that period, of which number 150 were published by Jenson.

Bibliography:

-

Thomas Aquinas, Saint, 1225?-1274. Incipit tabula cap[itu]lo[rum] libri [contra] ge[n]tiles b[ea]ti Thome de Aquino. [Venice : Nicolas Jenson, 1480] BX1749 .T38 1480

-

Thomas Aquinas, Saint, 1225?-1274. Summa contra gentiles : libri quatuor Thomae Aquinatis, ad lectionem codicis autographi in Bibliotheca Vaticana adservati, probatissimorum codicum meliorisque notae editionum, fideliter impressi ; volumen unicum. Romae : Ex typographia Forzanii et Socii, 1894. BX1749.T38 1894

-

Corpus Thomisticum Sancti Thomae de Aquino. http:/www.corpusthomisticum.org

-

Jenson, Nicolas, ca. 1420-1480. The last will and testament of the late Nicolas Jenson, printer, who departed this life at the city of Venice in the month of September, A.D. 1480. [Chicago, Ludlow Typograph Co., 1928] Z232.J54 L3 1928

This semester, get acquainted with Special Collections and Rare Books by playing Tuesday Trivia! Each week, we’ll post a question on our Facebook page. Be the first to leave a comment on Facebook with the correct answer, and we’ll send you a Special Collections bookmark. At the end of each month, the person with the most correct answers will win a “grand prize” – including packs of Special Collections notecards, publications, and more.

This semester, get acquainted with Special Collections and Rare Books by playing Tuesday Trivia! Each week, we’ll post a question on our Facebook page. Be the first to leave a comment on Facebook with the correct answer, and we’ll send you a Special Collections bookmark. At the end of each month, the person with the most correct answers will win a “grand prize” – including packs of Special Collections notecards, publications, and more.

The current student newspaper, the

The current student newspaper, the

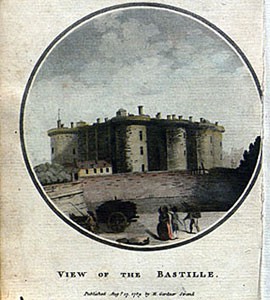

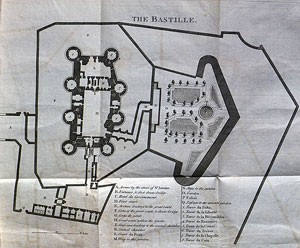

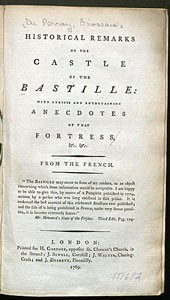

Although the Bastille could only hold around 50 prisoners, the rumors and mystery that surrounded it caused the prison to loom large in French culture. Rebellious subjects, religious dissenters, journalists, common criminals and those who simply incurred the king’s displeasure were all confined there. No one really knew what happened in the Bastille; prisoners were forced to take an oath of secrecy, promising never to divulge anything they saw or heard while inside the walls.

Although the Bastille could only hold around 50 prisoners, the rumors and mystery that surrounded it caused the prison to loom large in French culture. Rebellious subjects, religious dissenters, journalists, common criminals and those who simply incurred the king’s displeasure were all confined there. No one really knew what happened in the Bastille; prisoners were forced to take an oath of secrecy, promising never to divulge anything they saw or heard while inside the walls.

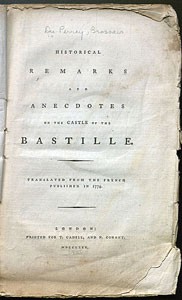

In 1774, a different type of pamphlet was published:

In 1774, a different type of pamphlet was published:  ns: each has two great bolts, and as many locks. … There are five ranks of chambers. The most dreadful next to the dungeons, are those in which are iron cages or dungeons. Of these there are three. These cages are formed of beams lined with strong iron plates. They are six feet by eight.

ns: each has two great bolts, and as many locks. … There are five ranks of chambers. The most dreadful next to the dungeons, are those in which are iron cages or dungeons. Of these there are three. These cages are formed of beams lined with strong iron plates. They are six feet by eight. In the rest of Europe, the pamphlet gained acceptance as a true and accurate depiction of the Bastille. English editions of the pamphlet came out in 1780 and 1784, and a new translation was issued after the storming of the Bastille in 1789. The English criminologist and reformer John Howard endorsed it as “the best account of this celebrated structure ever published” and included content from the pamphlet in his survey of European penitentiaries.

In the rest of Europe, the pamphlet gained acceptance as a true and accurate depiction of the Bastille. English editions of the pamphlet came out in 1780 and 1784, and a new translation was issued after the storming of the Bastille in 1789. The English criminologist and reformer John Howard endorsed it as “the best account of this celebrated structure ever published” and included content from the pamphlet in his survey of European penitentiaries.

Our book looks characteristically mediaeval: in contemporary brown tooled leather binding over wooden boards with the front half of embossed metal clasps still present. The title is written in a contemporary hand on the fore-edge and at the top of the blank recto of the first printed page: Tho[mae] [contra] gentiles. The watermarks {a crown without arch between two chain-lines} suggest that Jenson bought the paper from Genf (Genève), and the binder of the book had a paper stock {watermark: Virgin Mary in a shield} produced in Dorpat (modern Tallinn) or Riga in Livonia in the 15th century.

Our book looks characteristically mediaeval: in contemporary brown tooled leather binding over wooden boards with the front half of embossed metal clasps still present. The title is written in a contemporary hand on the fore-edge and at the top of the blank recto of the first printed page: Tho[mae] [contra] gentiles. The watermarks {a crown without arch between two chain-lines} suggest that Jenson bought the paper from Genf (Genève), and the binder of the book had a paper stock {watermark: Virgin Mary in a shield} produced in Dorpat (modern Tallinn) or Riga in Livonia in the 15th century.

The text is rubricated with red and blue capitals. A large and very elaborate first capital “v” in “Veritatem” opens the book, and each objection and counter argument is marked with red paragraph mark up to Book Four, chapter 11; after that, hand written capital letters at the beginning of chapters continue, but paragraph marks are much rarer and frequently coincide with short contemporary notes in the text, as if a reader was rubricating while reading.

The text is rubricated with red and blue capitals. A large and very elaborate first capital “v” in “Veritatem” opens the book, and each objection and counter argument is marked with red paragraph mark up to Book Four, chapter 11; after that, hand written capital letters at the beginning of chapters continue, but paragraph marks are much rarer and frequently coincide with short contemporary notes in the text, as if a reader was rubricating while reading.

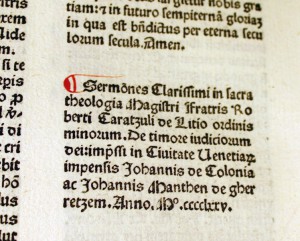

The author of this book, Fra Roberto Caracciolo de Lecce, was one of the most successful preachers of the fifteenth century, hailed as a “second St. Paul” for his oratorical talents.

The author of this book, Fra Roberto Caracciolo de Lecce, was one of the most successful preachers of the fifteenth century, hailed as a “second St. Paul” for his oratorical talents.

lumes of their sermons in Latin and vernacular Italian. Caracciolo alone had at least eight different editions of his sermons printed throughout Italy from the 1470s until his death in 1495. By the time the sixteenth century drew to a close, over one hundred editions of his works had been printed throughout Europe.

lumes of their sermons in Latin and vernacular Italian. Caracciolo alone had at least eight different editions of his sermons printed throughout Italy from the 1470s until his death in 1495. By the time the sixteenth century drew to a close, over one hundred editions of his works had been printed throughout Europe.

As Caracciolo’s career as a preacher reached its height, Italy stood on the brink of a technological revolution. Gutenberg had developed movable type in Mainz around 1455, but it took about a decade for the technology to reach Italy. Venice had to wait even longer – until 1469. That’s the year that Johannes of Speyer emigrated from Mainz, got a five-year monopoly from the Doge, and set up shop as the city’s first printer.

As Caracciolo’s career as a preacher reached its height, Italy stood on the brink of a technological revolution. Gutenberg had developed movable type in Mainz around 1455, but it took about a decade for the technology to reach Italy. Venice had to wait even longer – until 1469. That’s the year that Johannes of Speyer emigrated from Mainz, got a five-year monopoly from the Doge, and set up shop as the city’s first printer.

nthen de Gerresheim. Colonia and Manthen became the senior partners in the business; Vindelinus’ name disappeared from the company until 1476.

nthen de Gerresheim. Colonia and Manthen became the senior partners in the business; Vindelinus’ name disappeared from the company until 1476.

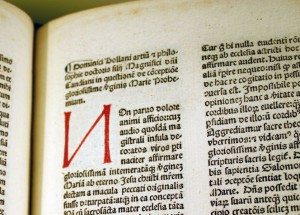

elegant Gothic. Like many other early printed books, the printers left space for initials and ornament to be added by hand. In this copy, several of the initial Ns are written backwards, for what reason we do not know.

elegant Gothic. Like many other early printed books, the printers left space for initials and ornament to be added by hand. In this copy, several of the initial Ns are written backwards, for what reason we do not know.

Aguzzi-Barbagli, Danilo. “Roberto Caracciolo of Lecce,c. 1425-6 May 1495.” In

Aguzzi-Barbagli, Danilo. “Roberto Caracciolo of Lecce,c. 1425-6 May 1495.” In