Resources and Services

National Library Week

Open Access Fees: Handy Comparison Chart

Looking for a list of Open Access fees? Check out the Eigenfactor Cost Effectiveness of Open Access Journals: http://www.eigenfactor.org/openaccess/index.php

Veterinary Journals: http://www.eigenfactor.org/openaccess/index.php?catid=38&pt=0

More info: http://www.nature.com/news/price-doesn-t-always-buy-prestige-in-open-access-1.12259

Friends of the Libraries Luncheon

Date: April 20, 2013

Time: Noon – 2:30 p.m.

Place: Reynolds Alumni Center, Great Room, University of Missouri

Keynote Speaker: Steven Watts, Ph.D.

MU Professor Steven Watts specializes in the cultural and intellectual history of the United States. His book, The Republic Reborn (1989), won the annual book prize from the National Historical Society and was runner-up for the best book award from the American Studies Association. In 2001, he published The Magic Kingdom, which was reviewed in major media venues throughout the country, including The New York Times, Washington Post and Los Angeles Times. His work on Walt Disney led to an appearance in the documentary, “Makers of the Twentieth Century,” and his expertise on Henry Ford led to his appearance on the documentary “Money and Power.” His latest work is the biography, Mr. Playboy: Hugh Hefner and the American Dream (2009). Professor Watts will be speaking about his upcoming book scheduled for release in October 2013, Self-Help Messiah: Dale Carnegie and Success of Modern America.

Tickets are $25 per person. Please contact, Sheila Voss to purchase tickets at vosss@missouri.edu or 573-882-4701.

Happy birthday, Thomas Moore Johnson!

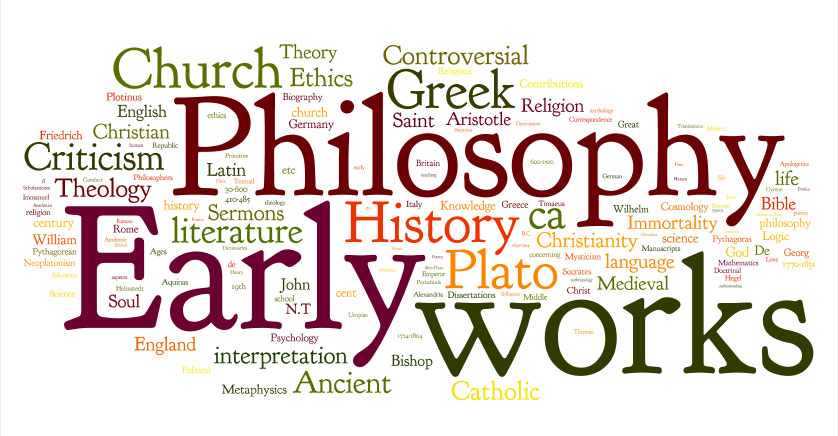

Today is the 162nd birthday of Thomas Moore Johnson, the namesake of the Thomas Moore Johnson Collection of Philosophy here in Special Collections. What's in the collection?

The graphic above is a Wordle of all the Library of Congress subject headings in the collection – so you can see that it really is a collection of philosophy. Johnson was interested in Plato and focused his collecting in that area. The oldest imprint is 1494, and there are several hundred volumes with publication dates from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The majority of the collection dates from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Thomas Moore Johnson (1851-1919) was an attorney, collector, and student of philosophy in Osceola, Missouri. Johnson began collecting Greek texts while a student at the University of Notre Dame and his library eventually grew to about 8,000 volumes.

A portion of his library was presented to the University of Missouri-Columbia Libraries in 1947 by his son, Franklin P. Johnson. Another part of the collection remains in Osceola as the Thomas Moore Johnson Library.

What’s in the box?

Last week I posted a picture on our Facebook page of a 320-pound special delivery we received. Are you dying to know what's in the box?

It's a wonderful collection of rare Kipling first editions and other Kiplingiana, donated to the Libraries by the estate of a generous donor, Helen Jenkins. Staff members took a first look at the collection yesterday and found some great materials, including first editions, pamphlets, ephemera, and limited editions.

It's a wonderful collection of rare Kipling first editions and other Kiplingiana, donated to the Libraries by the estate of a generous donor, Helen Jenkins. Staff members took a first look at the collection yesterday and found some great materials, including first editions, pamphlets, ephemera, and limited editions.

We will be working on cataloging this collection and making it available to researchers in the Special Collections reading room. Email SpecialCollections@missouri.edu with any questions.

Interview with Rajmohan Gandhi

MU Libraries presents:

An Interview with Rajmohan Gandhi

“The India-Pakistan Conflict and The Path to Stability”

April 12, 2013 at 11:00 a.m., light refreshments at 10:30 a.m.

Stotler Lounge, Memorial Union

Dr. Charles Davis from the Missouri School of Journalism will hold a wide-ranging conversation with Dr. Rajmohan Gandhi, biographer and grandson of Mahatma Gandhi, and former President of Initiatives of Change. Their conversation will touch on the endless quest for world peace, Gandhi’s work in the Indian-Pakistani realm, and why the simmering conflict matters to all citizens of the world.

Gandhi has written widely on the Indian independence movement and its leaders, Indo- Pakistan relations, human rights and conflict resolution. His recent book, A Tale of Two Revolts: India’s Mutiny and the American Civil War, demonstrates the commonality shared by two countries on opposites sides of the globe struggling for freedom in the nineteenth century.

Friday evening Dr. Gandhi will also speak at the Library Society Dinner in Ellis Library. For details on the Society dinner, please contact Sheila Voss at vosss@missouri.edu.

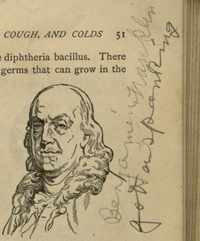

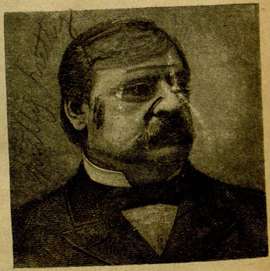

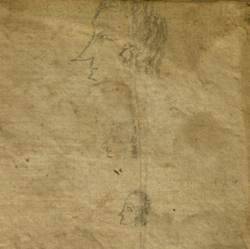

Historic Doodles

The week before spring break is traditionally a difficult time for students to remain focused on their books. Our collection of historic textbooks offers evidence that this trend is not new. Wide margins have always provided opportunities to practice one's signature. The bald pates of historic personages have always asked to be filled in with comb-overs.

Historic textbooks are an excellent resource, not only for those investigating the history of pedagogy, but also for those interested in getting a picture of the values and ideologies of any given historical moment. Ours is a diverse collection, comprising volumes from 1770 to 1929 and representing such core subjects as Arithmetic, and "Rhetorick," as well as less conventional subjects. American Handy Book of the Brewing, Malting, and Auxiliary Trades sits next to a handwriting manual. Some textbooks defy disciplinary boundaries altogether. The title page of Thomas Wise's The Newest Young Man's Companion of 1770 (right) announces that it includes "a compendious English grammar, letters on compliment, arithmetic and bookkeeping, a compendium of geography, the management of horses, and the art of painting in oil and water colours."

Historic textbooks are an excellent resource, not only for those investigating the history of pedagogy, but also for those interested in getting a picture of the values and ideologies of any given historical moment. Ours is a diverse collection, comprising volumes from 1770 to 1929 and representing such core subjects as Arithmetic, and "Rhetorick," as well as less conventional subjects. American Handy Book of the Brewing, Malting, and Auxiliary Trades sits next to a handwriting manual. Some textbooks defy disciplinary boundaries altogether. The title page of Thomas Wise's The Newest Young Man's Companion of 1770 (right) announces that it includes "a compendious English grammar, letters on compliment, arithmetic and bookkeeping, a compendium of geography, the management of horses, and the art of painting in oil and water colours."

Though in many respects historic textbooks differ from their modern counterparts, in one respect they are the same. They all bear witness to their owners' distraction. Paste downs can be filled in with faces. Margins provide space for recording personal notes that will perplex later generations, such as "This is a day of days," (below) scrawled next to the life cycle of the mosquito.

In between reading about the Monroe Doctrine and the history of the American flag, a student using an 1885 edition of A Brief History of the United States found time to compose the following message to the reader: "Before you find out what I have got to say, page 28 you'll have to see." On page 28, the student continues, "It grieves me to think of the trouble you have taken but look on page 4." There follow a total of seven directions until the final injunction concludes, "You fool don't you know better than to chase this book from cover to cover?"

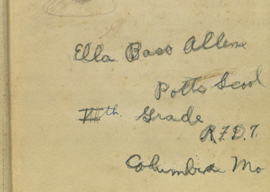

One wonders if amidst so many pages of instructions, students liked to issue some of their own. Ella Allen was a seventh grader at Potts School in 1920. She provides the following instructions on the pastedown of Primer of Sanitation, Being a Simple Textbook on Disease Germs and How to Fight Them. "If this book should go to Rome, Just give it a kick and send it home." Her book did not make it to Rome–Potts School was in Columbia, Missouri. But maybe Ella made it to Italy one spring. One would hope she had paid enough attention to her primer to avoid the Roman fever that did away with so many of her headstrong, fictional contemporaries.

Animal Health SmartBrief

Get a daily email of the latest news of importance to veterinarians and animal health professionals. Sign up for Animal Health SmartBrief from the AVMA. http://www.smartbrief.com/news/avma/