This April Fool’s Day we thought we’d share several editions of Moriae Encomium by Desiderius Erasmus, which, in addition to being a definitive resource on fools and foolishness, has a great Latin pun for a title.

Frontispiece portrait of Erasmus, engraving after Hans Holbein (London, 1709).

Frontispiece portrait of Erasmus, engraving after Hans Holbein (London, 1709).

Frontispiece and engraved title page featuring Erasmus, More, Holbein, and Folly as a goddess (Leiden, 1715).

Frontispiece and engraved title page featuring Erasmus, More, Holbein, and Folly as a goddess (Leiden, 1715).

The folly of scholarship, engravings after Hans Holbein (Paris, 1715).

The folly of scholarship, engravings after Hans Holbein (Paris, 1715).

Frontispiece illustration of Folly as a goddess, illustration after Charles Eisen (Paris, 1757).

Frontispiece illustration of Folly as a goddess, illustration after Charles Eisen (Paris, 1757).

The folly of drunkenness, engraving after Charles Eisen (Paris, 1757).

The folly of drunkenness, engraving after Charles Eisen (Paris, 1757).

Various types of folly, engravings after Daniel Chodowiecki (Berlin, 1781).

Various types of folly, engravings after Daniel Chodowiecki (Berlin, 1781).

The folly of pedagogues, mezzotint by Lynd Ward (New York, 1953).

The folly of pedagogues, mezzotint by Lynd Ward (New York, 1953).

Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) isn’t the figure one would suppose to be an authority on foolishness. Ordained as a priest and consecrated as a monk, Erasmus spent his life as a classical scholar, humanist, and theologian. Although he is best known for theological work, he was also a prolific and engaging author whose works ranged from popular handbooks on children’s table manners to bitter mockeries of Church and state officials.

The Praise of… More?

Around 1498, Erasmus moved to England, where he met Sir Thomas More, the author of Utopia. The two men worked together on a translation of the works of Lucian and became close friends. Erasmus moved to Italy to pursue a doctorate in divinity in 1500, but he and More continued to write to each other regularly.

In 1509, Erasmus returned to England and wrote Moriae Encomium during his journey, dedicating it to More. The title of the work makes an affectionate joke of More’s last name – Moriae Encomium can be translated as either The Praise of Folly or The Praise of More. Erasmus continued the wordplay throughout the text, parodying the elaborate literary style both he and More would have encountered in their classical studies.

Erasmus considered Moriae Encomium a minor work and was surprised and dismayed at its popularity upon its first publication in 1511. The work went through multiple editions and translations in his lifetime, and it touched off an entirely new literary genre – the spoof encomium, which became popular among learned Elizabethans.

Picturing Folly

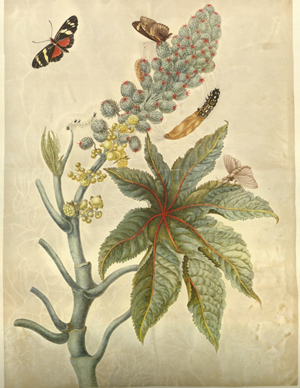

Moriae Encomium also gave rise to an artistic tradition. The artist Hans Holbein, a mutual friend of Erasmus and More, decorated Erasmus’ own copy of the book with marginal drawings. Holbein’s humorous doodles were adapted as engravings in a later edition, and they were copied for the next two hundred years. They have served as an inspiration – or a point of departure – for the generations of artists who have illustrated this text.

The Division of Special Collections, Archives, and Rare Books has editions of Moriae Encomium ranging from the seventeenth through the twentieth centuries, and many are illustrated. In addition to Holbein, illustrators include Charles Eisen, Daniel Chodowiecki, and Lynd Ward. The images above are just a sampling from our collection. Enjoy!

Sources

-

L’Eloge de la Folie composé en forme de declamation… , illustrated with engravings after the designs of Hans Holbein (Leiden, P. vander Aa, 1715). RARE PA8514 .F8 1715

-

L’Eloge de la Folie, illustrated by Charles Eisen (Paris, n.p., 1757). RARE PA8514 .F8 1757

-

Moriae Encomium: or, A Panegyrick Upon Folly, illustrated with engravings after the designs of Hans Holbein (London, Printed, and sold by J. Woodward, in Threadneedle street, 1709). RARE PA8514.E5 1709

-

L’Eloge de la Folie, illustrated by Charles Eisen (Paris, n.p., 1757). RARE PA8514 .F8 1757

-

Moriae Encomium: or, The Praise of Folly, illustrated by Lynd Ward (New York: Limited Editions Club, 1943). RARE PA8514 .E5 1943

-

L’Eloge de la Folie composé en forme de declamation… , illustrated with engravings after the designs of Hans Holbein (Leiden, P. vander Aa, 1715). RARE PA8514 .F8 1715

-

Das Lob der Narrheit aus dem Lateinischen, illustrated by Daniel Chodowiecki (Berlin: G.J. Decker, 1781). RARE PA8514 .G3 1781

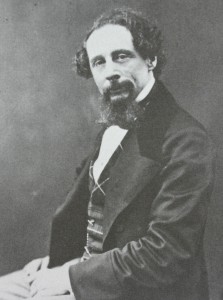

Charles John Huffam Dickens was born on this date in 1812. Dickens, one of the most famous and most belov

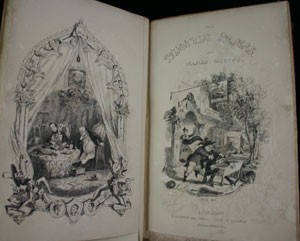

Charles John Huffam Dickens was born on this date in 1812. Dickens, one of the most famous and most belov ed of all English novelists, created some of the most powerful characters in fiction. He is known all over the world, and, unlike most great authors, he was rock-star famous in his own time. He moved around a lot as a child and was forced to quit school at twelve years old to work in a factory. Those early memories, however, would later inspire settings both fantastic and real; characters both legendary and sympathetic.

ed of all English novelists, created some of the most powerful characters in fiction. He is known all over the world, and, unlike most great authors, he was rock-star famous in his own time. He moved around a lot as a child and was forced to quit school at twelve years old to work in a factory. Those early memories, however, would later inspire settings both fantastic and real; characters both legendary and sympathetic.

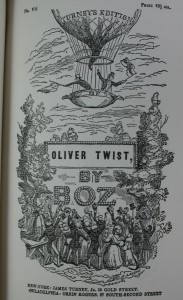

Sketches by Boz, The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop, Barnaby Rudge, and American Notes.

Sketches by Boz, The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop, Barnaby Rudge, and American Notes.

The first of these pairings was with George Cruikshank, a popular cartoonist at the time. The author and illustrator became great friends, though their relationship soured due to many factors including Cruikshank’s growing obsession with the Temperance movement.

The first of these pairings was with George Cruikshank, a popular cartoonist at the time. The author and illustrator became great friends, though their relationship soured due to many factors including Cruikshank’s growing obsession with the Temperance movement.

Knight Browne worked with Dickens for over 23 years. He adopted the nickname Phiz to complement Dickens’ Boz.

Knight Browne worked with Dickens for over 23 years. He adopted the nickname Phiz to complement Dickens’ Boz.

“No other illustrator ever created the true Dickens characters with the precise and correct quantum of exaggeration.”

“No other illustrator ever created the true Dickens characters with the precise and correct quantum of exaggeration.”

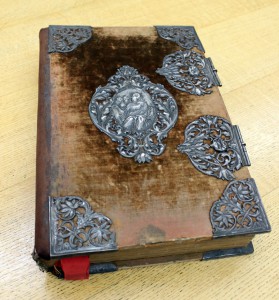

Celebrate his 200th birthday by dropping by Special Collections in Ellis Library to read the stories as Dickens so meticulously intended. We have many of his greatest works, some beautifully bound, dating from the beginning of the author’s literary career. Experience what created this pop sensation first-hand!

Celebrate his 200th birthday by dropping by Special Collections in Ellis Library to read the stories as Dickens so meticulously intended. We have many of his greatest works, some beautifully bound, dating from the beginning of the author’s literary career. Experience what created this pop sensation first-hand!