And spring things bring people who collect them –naturalists and artists such as Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), the first to hitch entomology to fine art and to make a living doing so. Her interests were not limited to European species; she spent two years stalking the insects of Surinam, a colony the Dutch had acquired from the English in exchange for Manhattan about thirty years earlier. She devoted an equal amount of attention to giant flying roaches as to seemlier species, but there is no question that she had a special passion for caterpillars.

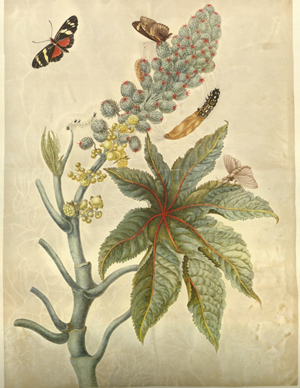

Merian's interest in metamorphosis led her to develop a new form of composition. She would depict a single species at each distinct phase simultaneously. She arranged these in a composition on and around the plant that formed its principal food source. In the image on the left several saw-fly specimens pose on a tulip. The caterpillar sits atop a gooseberry at the bottom center, while the adult fly prepares to land on a petal at the top right. In between on a stem and leaf are the pupa and larva. As Ella Reitsma, curator of a recent exhibit, observes about Merian's work, "In the details the drawing is realistic; as a whole it is anything but. The beautifully balanced composition conjures up a seeming realism, for the successive stages in the development of an insect can never be found together! Tricks have been played with time and place” (15)

Despite such innovation, Merian’s work languished for a long time under the misnomer “minor art.’ It has only recently come into its own, with exhibitions in Los Angeles and Amsterdam, and a digital exhibit hosted by The Dumbarton Oaks Research Library Rare Book Collection. She is even the subject of a children’s book. Ingrid Rowland notes her “crystalline accuracy, ” her “incomparable precision,” and the “electric intensity” of her use of color. She asserts, “there is no question that she was an artist. Her disquieting view of life in all its forms has carefully, cleverly shaped every one of the images that seem, so deceptively, to present intimate, dispassionate snapshots of reality.”

Pervading her works is a healthy Aristotelian sense that something must be known in all its variousness. Working alongside this cognitive disposition, and perhaps encouraging it, was a habit that she shared with many contemporaries: collecting. Her life-like compositions conceal the artificial taxonomizing and categorizing that lie behind them, making it appear as if she had discovered, rather than created the scene depicted.

These are qualities that Peter the Great evidently appreciated; he was an avid collector of her work, much of which remains in the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. In 1974 The Leningrad Watercolours is a facsimile edition featuring fifty of the works housed there. It is a large-format edition limited to 1750 copies. Several prints from the collection are available to view in our reading room. The entire collection collection (RARE QH31 .M4516 .A34 1974) is also available to consult.

Select Bibliography

Reitsma, Ella, Maria Sibylla Merian and Daughters: Women of Art and Science. Amsterdam : Rembrandt House Museum, 2008.

Rowland, Ingrid. “The Flowering Genius of Maria Sibylla Merian.” New York Review of Books. April 9, 2009.

Todd, Kim. Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis. Orlando: Harcourt, 2007.