PubGet…Ligercat…PubNet…what are all these things?

Here’s a handy comparison of biomedical literature search tools from NCBI.

You can even specify what kind of tool you’re interesting in: for example, visualizing search results using networks.

Your source for what's new at Mizzou Libraries

PubGet…Ligercat…PubNet…what are all these things?

Here’s a handy comparison of biomedical literature search tools from NCBI.

You can even specify what kind of tool you’re interesting in: for example, visualizing search results using networks.

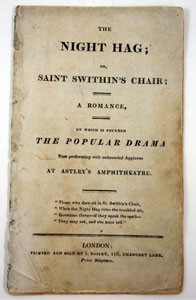

In honor of Halloween, we're posting an excerpt from one of the horror stories in the rare book collection, The Night Hag; or, St. Swithin's Chair: A Romance, which was published in the form of a small pamphlet by J. Bailey in the early nineteenth century (the pamphlet is undated). There are only two three copies reported in WorldCat, and Special Collections has the only reported copy of this text in the United States (2014 update: there's another copy reported in the U.S. now, at the University of Pittsburgh).

In honor of Halloween, we're posting an excerpt from one of the horror stories in the rare book collection, The Night Hag; or, St. Swithin's Chair: A Romance, which was published in the form of a small pamphlet by J. Bailey in the early nineteenth century (the pamphlet is undated). There are only two three copies reported in WorldCat, and Special Collections has the only reported copy of this text in the United States (2014 update: there's another copy reported in the U.S. now, at the University of Pittsburgh).

The star of the romance is Fergus Campbell, "a captain in the Scotch service then stationed in Edinburgh, in the reign of James the Sixth." Fergus' aunt is the wealthy Lady Margaret Mucklethrift, and Fergus is second in line after his cousin to inherit all of her money and property. Thirsty for riches, Fergus decides to rob his aunt of her riches and depose his cousin as her heir. After a series of failed plots, Fergus decides to seek supernatural help.

"It was now Hallow mass E'en, and Fergus thought of the ancient spell of St. Swithin's applicable to that season, that then the Night Hag, delighting in scenes of blood and murderous deeds, has full power.

He who dares sit on St. Swithin's chair,

When the Night Hag rides the troubled air,

Questions three, if they speak the spell,

They may ask, and she must tell."

Fergus asks his three questions and finds that he will indeed gain his aunt's incredible riches, with the Night Hag's treacherous help. After stabbing his aunt to death, with the household on the alert, Fergus hides in her iron-clad strong box. Will he be discovered?

No spoilers here! Of course, there's much more to the story: an innocent man framed for murder, a pair of star-crossed lovers, and a reformed criminal with a critical decision to make. Read more about it in Special Collections!

This pamphlet purports to be "a romance, on which is founded the popular drama now performing with unbounded applause at Astley's Amphitheatre." Several plays were produced under this title in the early nineteenth century, featuring Fergus Campbell, his unfortunate aunt, and the rest of the characters in the romance. Indeed, the first of these plays was performed at Astley's Amphitheatre and ran in September and October 1820. The playbill for this production said "The Idea from which the Subject is arranged [is] taken from the Interesting Legend of St. Swithin's Chair, in Walter Scott's Popular Novel of Waverly."

This pamphlet purports to be "a romance, on which is founded the popular drama now performing with unbounded applause at Astley's Amphitheatre." Several plays were produced under this title in the early nineteenth century, featuring Fergus Campbell, his unfortunate aunt, and the rest of the characters in the romance. Indeed, the first of these plays was performed at Astley's Amphitheatre and ran in September and October 1820. The playbill for this production said "The Idea from which the Subject is arranged [is] taken from the Interesting Legend of St. Swithin's Chair, in Walter Scott's Popular Novel of Waverly."

The problem? The interesting legend of St. Swithin's Chair, as far as it pertains to Fergus Campbell, isn't in Waverley. The novel includes a poem entitled "St. Swithin's Chair", based on an old Scottish legend, but that's all. In his 1992 catalog of playbills and scripts based on Scott's works, H. Philip Bolton notes the difficulty in relating The Night Hag to Waverley, judging the play "doubly apocryphal."

How does this pamphlet relate to the Night Hag plays of the nineteenth century? When was it published? And, perhaps most importantly, who was its author?

At this point, we don't know. If you're a researcher in this area, come finish the story, and help us find out.

Bolton, H. Philip. Scott dramatized. London ; New York : Mansell, 1992.

Thanks to the generous support of donors to the Friends of the MU Libraries Adopt-A-Book program, conservator Jim Downey has been able to treat and repair a number of books from Special Collections. Below is a sampling of before and after pictures from the latest batch of adoptees; click over to the Adopt-A-Book web site for more. A sincere thanks to donors George Justice, H. & D. Moore, B. Winfield, M. Nagar, W. Oshinsky, P. Collins, J. Schweitzer, R. Drake and M. Correale.

Check out the VOX feature on Tim and Terry!

A commonly used three-drug regimen for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis was found harmful in an NIH clinical trial. In the trial, the triple-drug therapy consisting of prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) had poorer outcomes than placebo or inactive substances. NIH stopped the three-drug regimen arm of the trial.

The complete text for the alert is available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/databases/alerts/2011_nhlbi_ifp.html

In 1911, Chester Brewer invited old grads to “come home” for the KU game, and a tradition was born. This exhibit located in the Ellis Library colonnade takes a look back at one hundred years of homecoming history. The exhibit will be on display for the month of October.

Celebrate Open Access Week! Check out the MU Libraries home page for the Price That Journal contest…