You might think I'm cheating a bit with this week's Unsolved Mystery. After all, this manuscript is catalogued; it's even fully digitized! We know where it came from, how we got it, and we have a general outline of its contents. Not much of a mystery, right?

Well, like most of our Unsolved Mysteries, there are more pieces of the story to uncover.

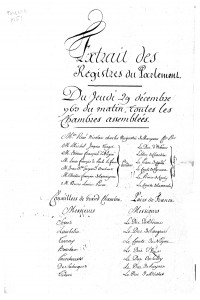

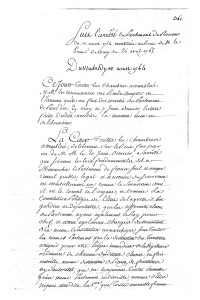

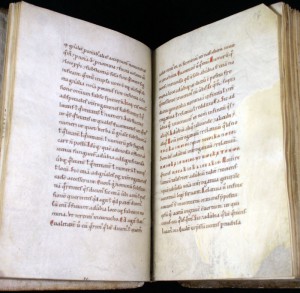

This manuscript on the laws of Paris and the French Parliament is attributed to Monsieur Drouyn de Vandeuil, the first President of the Parliament of Toulouse, and contains a history of France and a register of French royalty. There is also an extract of the minutes of the French Parliament. The manuscript seems to have been written by two separate scribes. We assume it's a fair copy of minutes and other working documents.

This manuscript belonged to the French lawyer and bibliophile Jacques Flach. His collection was purchased by the University of Missouri in 1920, and the manuscript has been here ever since. It is available through the University of Missouri Digital Library.

To our knowledge, the manuscript has never been published or studied – so we have an outline of the text, but we don't know its contents in detail.

How did Flach come across the manuscript? Is the attribution correct? Has the text ever been published? What information does it contain?

If you have information about this or any other of our unsolved mysteries, email us at SpecialCollections@missouri.edu – and stay tuned for another Special Collections mystery next week.

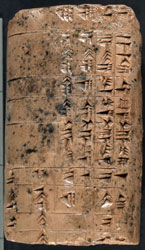

As far as we know, this cuneiform tablet dates to around 2500 B.C.E., making it the oldest item held in Special Collections (it predates the next oldest item, an Egyptian scarab seal, by about 500 years).

As far as we know, this cuneiform tablet dates to around 2500 B.C.E., making it the oldest item held in Special Collections (it predates the next oldest item, an Egyptian scarab seal, by about 500 years).

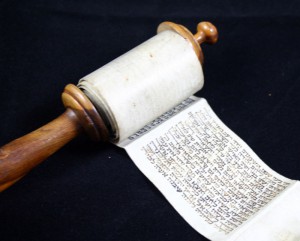

If you guessed that the scroll represents the oldest book form in Special Collections, you were right! The scroll predated the codex (the form we usually associate with a book nowadays) by thousands of years.

If you guessed that the scroll represents the oldest book form in Special Collections, you were right! The scroll predated the codex (the form we usually associate with a book nowadays) by thousands of years.

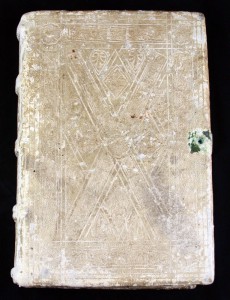

This manuscript copy of De Constructione by Priscianus dates to around 1150 A.D. Although Special Collections holds manuscript fragments that are older, this is the oldest complete book in the collection. It is a work on grammar, written in Latin with passages in Greek.

This manuscript copy of De Constructione by Priscianus dates to around 1150 A.D. Although Special Collections holds manuscript fragments that are older, this is the oldest complete book in the collection. It is a work on grammar, written in Latin with passages in Greek.

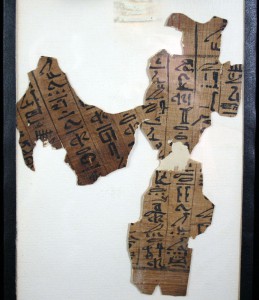

Dating from approximately 1500-1100 B.C.E., this fragment from the Egyptian Book of the Dead isn’t the oldest item in Special Collections – but it is the oldest piece of writing on papyrus in Special Collections.

Dating from approximately 1500-1100 B.C.E., this fragment from the Egyptian Book of the Dead isn’t the oldest item in Special Collections – but it is the oldest piece of writing on papyrus in Special Collections.