Today marks the beginning of Banned Books Week, a yearly celebration of the freedom to read. Special Collections is home to many banned books, and our extensive Comic Art Collection of more than 15,000 comic books contains some of the most-suppressed literature in the library.

Horror and Suspense

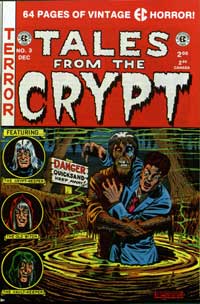

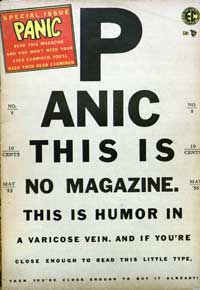

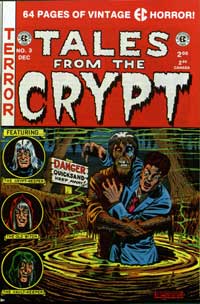

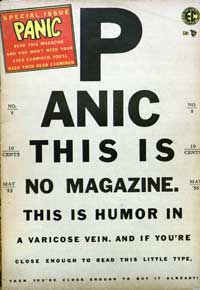

Horror, crime, and suspense comics became quite popular in the late 1940s and early 1950s. EC Comics, edited by Al Feldstein and Harvey Kurtzman, was one of the main publishers of this type of literature. The company published several highly popular titles, including Tales from the Crypt, Frontline Combat, Panic, and Shock SuspenStories.

Horror, crime, and suspense comics became quite popular in the late 1940s and early 1950s. EC Comics, edited by Al Feldstein and Harvey Kurtzman, was one of the main publishers of this type of literature. The company published several highly popular titles, including Tales from the Crypt, Frontline Combat, Panic, and Shock SuspenStories.

Sparked by the publication of Seduction of the Innocent by psychiatrist Frederic Wertham, movements to censor these types of comics began popping up around the country after World War II. Wertham claimed that children would be conditioned to emulate what they saw on the pages of the comics, and that an entire generation was at risk of moral and mental corruption because of their reading material. Congress held an official inquiry on comics and juvenile delinquency in 1954, and many cities throughout the country passed or considered municipal bans on comic books in general.

The Comics Code Authority

Fearing government regulation, the comics industry turned to self-censorship, forming the Comics Code Authority (CCA) in late 1954. The Code set a number of content and artistic standards, including the stipulation that good must always triumph over evil, a general ban on the words “horror” and “terror” in comic book titles, and strict guidelines for the handling of crime, race, sexuality, and political issues.

Fearing government regulation, the comics industry turned to self-censorship, forming the Comics Code Authority (CCA) in late 1954. The Code set a number of content and artistic standards, including the stipulation that good must always triumph over evil, a general ban on the words “horror” and “terror” in comic book titles, and strict guidelines for the handling of crime, race, sexuality, and political issues.

Although the CCA had no legal power, most distributors refused to carry comics without the CCA seal of approval. Some publishers adapted to the new regulations, while others went out of business. EC Comics cancelled all of its titles except for Mad magazine (which was not subject to the Code), and was later absorbed by DC Comics.

The Comics Code remained in effect as it was written in 1954 until it was challenged by Marvel over a Spider-Man cover in 1971. The Code’s authority began to break down in the late 1980s, but it remained in force with major publishers until Marvel officially abandoned the Code in 2001, and DC dropped it in 2011.

Underground Comics

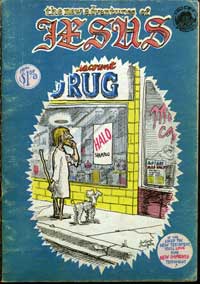

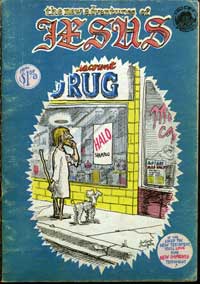

By the late 1960s, artists began exploring themes banned by the Code in self-published or small-press “underground” comics. Many were inspired directly by EC Comics, Mad, and the work of Harvey Kurtzman.

By the late 1960s, artists began exploring themes banned by the Code in self-published or small-press “underground” comics. Many were inspired directly by EC Comics, Mad, and the work of Harvey Kurtzman.

Frank Stack, an emeritus professor of art at MU, is credited with creating the first underground comic book when he published The Adventures of Jesus in 1964 under the pseudonym Foolbert Sturgeon. Artists such as Gilbert Shelton and R. Crumb also established the genre with publications such as The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers and Fritz the Cat.

Crumb stated that the appeal of underground comics was their lack of censorship – and this is certainly expressed in their content. Many underground comics offer commentary on drug use, sex, racism, the anti-war movement, and women’s rights. These were all topics that could not easily be treated by mainstream comics publishers.

Book Banning Continues

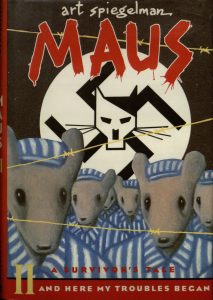

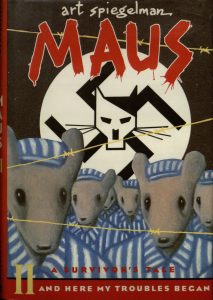

Comics and graphic novels of all genres, particularly those for children and teens, remain reading materials often targeted by bans. The American Library Association releases a yearly list of the top 10 most challenged books, and graphic novels often figure among them. Fun Home by Alison Bechdel, Genderqueer by Maia Kobabe, Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, and, most recently, Maus by Art Spiegelman are all graphic novels that have been banned or challenged in public and school libraries. They and many others are represented in the Comic Art Collection in Special Collections, where they are available to all.

Comics and graphic novels of all genres, particularly those for children and teens, remain reading materials often targeted by bans. The American Library Association releases a yearly list of the top 10 most challenged books, and graphic novels often figure among them. Fun Home by Alison Bechdel, Genderqueer by Maia Kobabe, Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, and, most recently, Maus by Art Spiegelman are all graphic novels that have been banned or challenged in public and school libraries. They and many others are represented in the Comic Art Collection in Special Collections, where they are available to all.

For more information about current attempts to ban books, see Mapping Censorship from the Banned Books Week website and the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

This post was originally written for Banned Books Week 2012 and was updated in January 2022.