My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause.

– President Lincoln’s public response to Horace Greeley’s open letter published in the New York Times, August 22, 1962

Today, the brand new start to a New Year, marks the 150th anniversary of what is arguably the most important document of the 19th century. Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not outlaw slavery, nor make former slaves citizens, the Proclamation did announce that all slaves in the Confederates States that were still under rebellion were free and ordered the Union Army to treat any slaves they found in the rebellious states as such. However, there were five slave states not under rebellion. Of the estimated 4 million slaves in the United States at the time, the Emancipation Proclamation only applied to 3.1 million.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God

– Emancipation Proclamation, January 1, 1863

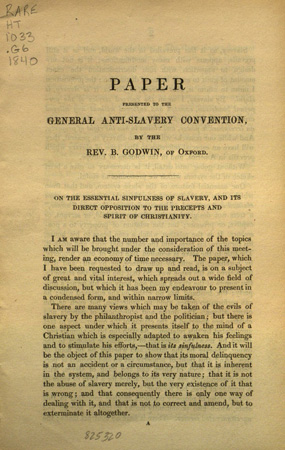

Slavery, of course, had been a contentious issue not only in American history, but in the history of many different nations for centuries. At Special Collections, we have many different print and microform sources on the subject of slavery and abolitionism. Even though slavery nearly tore apart the United States, a great majority of our sources were published in London. Before and after the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 by the British Parliament, abolitionists from all over wrote impassioned speeches and sermons decrying the evils of slavery. Pictured here is one such speech delivered by Reverend Benjamin Godwin of Oxford to the General Anti-Slavery Convention.

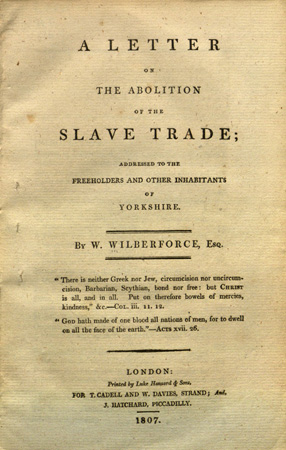

One of the greatest, and certainly the most earnest, British abolitionists was William Wilberforce. Wilberforce took up the cause of ending slavery in 1787. It took a full twenty years of fighting before Wilberforce saw his first victory.

The Slave Trade Act of 1807 ended the commerce of buying and selling human beings throughout the British Empire, but it did not end slavery itself. Buoyed by his success in 1807, Wilberforce and his compatriots assumed that a full ban on slavery would be forthcoming. They were wrong. It took another twenty-six years for slavery to end throughout the British Empire, only three days before Wilberforce passed away at the age of seventy-three. The story of his lifelong work to end slavery was told in a major motion picture, Amazing Grace, which was released in 2007 to coincide with the 200th anniversary of the Slave Trade Act of 1807.

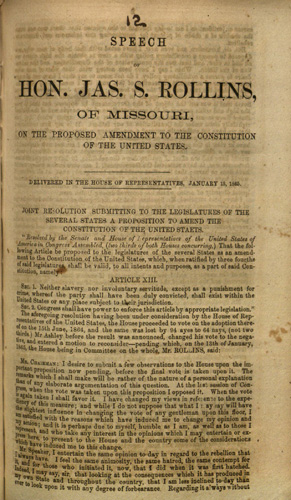

Back in the United States, many of the great statesmen of our nation changed their mind on the subject. Thomas Jefferson is known as a slaveholder, but also someone who spoke on the eventual dismantling of the institution. In 1807, Jefferson signed into law a bill that banned the importation of slaves into the United States. In Missouri, our very own Representative James S. Rollins, known as the Father of the University of Missouri, was also a slave owner. Rollins was reticent at first to completely abolishing slavery. However, he opposed the expansion of slavery and the secessionist movement that turned into the American Civil War.

Despite initially stating that the Emancipation Proclamation was legally void, he was eventually one of the most important supporters of the 13th Amendment in 1865, which completely outlawed slavery everywhere in the United States. His speech on the floor of the House was pivotal in bringing in the two-thirds majority needed for the amendment to become law. That speech is reproduced in a volume in Special Collections’ MU collection.

As for President Lincoln, his Emancipation Proclamation fundamentally changed the Civil War. The proclamation provided for the addition of former slaves into the Union forces, increasing the number of soldiers and sailors by almost 200,000. While the Confederate States were being depleted of fighting men, the Union was gaining more. Furthermore, the proclamation ignited a new fervor in the north, the idea that with every square mile of ground gained by the Union was more land that was now free from bondage and slavery gave the North the needed boost and a moral imperative to win the war. Today, the original Emancipation Proclamation resides in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. alongside other famous documents including the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and one of the original copies of the Magna Carta.