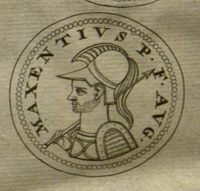

On October 28 in 312 A.D. Constantine defeated the superior forces of his rival Maxentius at the battle of Milvian Bridge. Maxentius’s forces attempted to retreat across the Tiber by way of the Milvian Bridge, but the bridge quickly became overcrowded. As Lactantius records in De Mortibus Persecutorum, or The Deaths of the Persecutors, "the army of Maxentius was seized with terror, and he himself fled in haste to the bridge which had been broken down; pressed by the mass of fugitives, he was hurtled into the Tiber" (44.9 ).

On October 28 in 312 A.D. Constantine defeated the superior forces of his rival Maxentius at the battle of Milvian Bridge. Maxentius’s forces attempted to retreat across the Tiber by way of the Milvian Bridge, but the bridge quickly became overcrowded. As Lactantius records in De Mortibus Persecutorum, or The Deaths of the Persecutors, "the army of Maxentius was seized with terror, and he himself fled in haste to the bridge which had been broken down; pressed by the mass of fugitives, he was hurtled into the Tiber" (44.9 ).

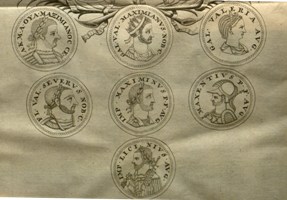

Diocletian had planted the seeds of this civil war. In the 49 years before his accession, Rome had had 26 rulers, most of whom met with a violent end. In an attempt to stabilize imperial succession, he introduced the system of tetrarchy, in which the empire was divided into two halves, each governed by a senior emperor assisted by a junior emperor who would eventually accede to his office. When Diocletian and his co-emperor, Maximian, retired, their successors jointly acceded to their offices. But Diocletian's plan derailed when these new emperors appointed their successors. Many hopefuls, including Constantine and Maxentius, felt they had been denied their rightful claim. Constantine's claim arose from the fact that his father had been sub-emperor under Maximian and was now emperor of the West. Maxentius, as the son of the Maximian–the emperor whom Constantine’s father had replaced–also felt slighted. When Constantine’s father died, opening the office of emperor of the West, Constantine moved his army of 40,000 Gauls southward toward Rome, where his 40,000 troops would engage with the forces of Maxentius, 100,000 strong.

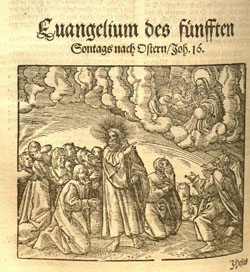

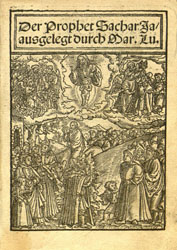

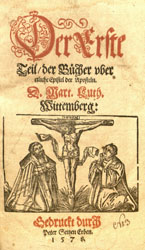

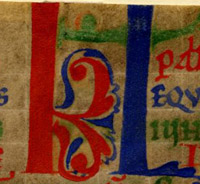

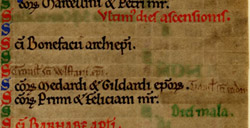

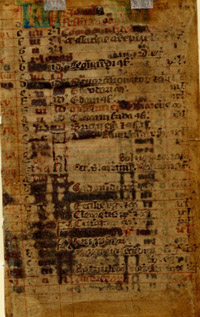

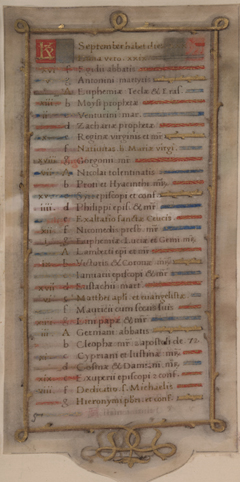

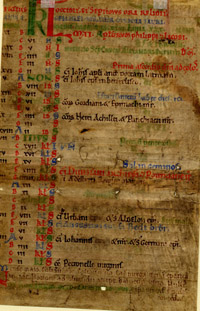

![]() Many early literary sources of information about Constantine survive. Special Collections and Rare Books houses several editions of both Lactantius’ De Mortibus Persecutorum and Eusebius’s Historia Ecclesiastica, along with one edition of the Chronicon. We also have eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literary and historical works that are heavily indebted to these sources. Click on the images to learn more about the particular edition pictured.

Many early literary sources of information about Constantine survive. Special Collections and Rare Books houses several editions of both Lactantius’ De Mortibus Persecutorum and Eusebius’s Historia Ecclesiastica, along with one edition of the Chronicon. We also have eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literary and historical works that are heavily indebted to these sources. Click on the images to learn more about the particular edition pictured.

Contemporary sources provide an idealized picture of Constantine, created to fulfill the various agenda of their authors. Lactantius lived in poverty until he found employment as tutor to Constantine’s son Crispus. Eusebius was invested in his theory about the proper relation between the church and state, and it was convenient to have an example so near at hand. Averil Cameron has duly noted “the eagerness of all parties to make claims on the rising star” (Cameron 91).

Constantine's contemporaries inflated his origins. In 310 A.D., an anonymous panegyrist of addressed Constantine as follows: “[Y]ou were born an Emperor, and so great is the nobility of your lineage that the attainment of imperial power has added nothing to your honor, nor can Fortune claim credit for your divinity, which is rightfully yours without campaigning and canvassing.” (Nixon 221) On the contrary, he had humble origins: he was the illegitimate child of a Jewish barmaid (allegedly a prostitute) and a Balkan peasant. When the latter's military success raised him into imperial ranks, he rearranged his personal affairs by adopting Constantine and making of Helen an honest woman.

His contemporaries also distorted his religious beliefs, seeing him as the hand of God, accomplishing His will on earth. Lactantius was one so inclined: "The hand of God was over the battle-line," he declares, in his account of the battle in De Mortibus Persecutorum (44.9). His was the earliest account we have of a vision that was to become very influential:

His contemporaries also distorted his religious beliefs, seeing him as the hand of God, accomplishing His will on earth. Lactantius was one so inclined: "The hand of God was over the battle-line," he declares, in his account of the battle in De Mortibus Persecutorum (44.9). His was the earliest account we have of a vision that was to become very influential:

"Constantine was advised in a dream to mark the heavenly sign of God on the shields of his soldiers and then engage in battle. He did as he was commanded and by means of a slanted letter X with the top of its head bent round, he marked Christ on their shields. Armed with this sign, the army took up its weapons." (44.5)

Eusebius, on the other hand, is silent on the issue of the vision in Historia Ecclesiastica of c. 323 A.D. But in his Life of Constantine, written sometime around 338 A.D., he revises his earlier account, devoting all his rhetorical powers to describing the vision. In doing so, he creates a scene that would remain in collective memory to this day:

“About the time of the midday sun, when day was just turning, he [Constantine] said he saw with his own eyes, up in the sky and resting over the sun, a cross-shaped trophy formed from light, and a text attached to it which said, ‘By this conquer’. Amazement at the spectacle seized both him and the whole company of soldiers which was then accompanying him on a campaign he was conducting somewhere, and witnessed the miracle.

“About the time of the midday sun, when day was just turning, he [Constantine] said he saw with his own eyes, up in the sky and resting over the sun, a cross-shaped trophy formed from light, and a text attached to it which said, ‘By this conquer’. Amazement at the spectacle seized both him and the whole company of soldiers which was then accompanying him on a campaign he was conducting somewhere, and witnessed the miracle.

He was, he said, wondering to himself what the manifestation might mean; then, while he meditated, and thought long and hard, night overtook him. Thereupon, as he slept, the Christ of God appeared to him with the sign which had appeared in the sky, and urged him to make himself a copy of the sign which had appeared in the sky, and to use this a protection against the attacks of the enemy (1.28).

When Constantine arrived at the gates of Rome, Maxentius hunkered down inside with his 100,000 troops. He probably could have successfully waited out the siege had he not misapplied an oracle: according to Lactantius, "he ordered the Sibylline books to be inspected; in these it was discovered that 'on that day the enemy of the Romans would perish.' Led by this reply to hope for victory, Maxentius marched out to battle" (DMP 44.7-8), and thereupon met his end. According to Eusebius, Constantine then "rode into Rome with songs of victory, and together with women and tiny children, all the members of the Senate and citizens of the highest distinction in other spheres, and the whole populace of Rome, turned out in force and with shining eyes and all their hearts welcomed him as deliverer, savior, and benefactor, singing his praises with insatiate joy." (HE 294)

Though the victory at Milvian Bridge has been associated in popular memory with the accession of Constantine and the triumph of Christianity, in fact, Maxentius was just one of several rivals for control of the Roman Empire; there were six total, including old Maximian, who came back out of retirement. Of one of them, Will Winstanely, author of England's Worthies, comments, “man proposeth, and God disposeth; for he who dreamt of nothing less than a glorious victory, was himself overcome by Licinius of Tarsus, where he shortly after died, being eaten up with Lice.” One by one, the contenders knocked each other off, until only Licinius remain. He was defeated in 323 A.D. , making Constantine the sole ruler of a united Empire until his death in 337 A.D.

Though the victory at Milvian Bridge has been associated in popular memory with the accession of Constantine and the triumph of Christianity, in fact, Maxentius was just one of several rivals for control of the Roman Empire; there were six total, including old Maximian, who came back out of retirement. Of one of them, Will Winstanely, author of England's Worthies, comments, “man proposeth, and God disposeth; for he who dreamt of nothing less than a glorious victory, was himself overcome by Licinius of Tarsus, where he shortly after died, being eaten up with Lice.” One by one, the contenders knocked each other off, until only Licinius remain. He was defeated in 323 A.D. , making Constantine the sole ruler of a united Empire until his death in 337 A.D.

***

Whatever role God might have played in the outcome of Constantine's military career, it is clear that Christianity is Constantine's legacy to European and Byzantine civilization. Constantine and Licinius jointly legalized Christianity with the Edict of Milan in 313 A.D., which proclaimed that “Christians and all other men should be allowed full freedom to subscribe to whatever form of worship they desire, so that whatever divinity may be on the heavenly throne may be well disposed and propitious to us, and to all placed under us." Edward Gibbon, who was not fond of revealed religion, casts a less than favorable light on the legalization of Christianity in Rome. He attributes the “fall” of the empire partially to the influence of Christianity to it because it instilled “patience and pusillanimity” until the “last remains of the military spirit were buried in the cloister.” Nonetheless, he concedes that “if the decline of the Roman empire was hastened by the conversion of Constantine, his victorious religion broke the violence of the fall, and mollified the ferocious temper of the conquerors.” For different reasons, modern historians concur in locating some of the blame in Constantine's policies. His founding of Constantinople exacerbated the division between Eastern and Western Empire, (a division started by Diocletian’s system of tetrarchy) and the concentration of wealth in the Eastern half. Both of these developments left the Western Empire an easy target for the barbarians, who would soon come flooding through the gates.

Whatever role God might have played in the outcome of Constantine's military career, it is clear that Christianity is Constantine's legacy to European and Byzantine civilization. Constantine and Licinius jointly legalized Christianity with the Edict of Milan in 313 A.D., which proclaimed that “Christians and all other men should be allowed full freedom to subscribe to whatever form of worship they desire, so that whatever divinity may be on the heavenly throne may be well disposed and propitious to us, and to all placed under us." Edward Gibbon, who was not fond of revealed religion, casts a less than favorable light on the legalization of Christianity in Rome. He attributes the “fall” of the empire partially to the influence of Christianity to it because it instilled “patience and pusillanimity” until the “last remains of the military spirit were buried in the cloister.” Nonetheless, he concedes that “if the decline of the Roman empire was hastened by the conversion of Constantine, his victorious religion broke the violence of the fall, and mollified the ferocious temper of the conquerors.” For different reasons, modern historians concur in locating some of the blame in Constantine's policies. His founding of Constantinople exacerbated the division between Eastern and Western Empire, (a division started by Diocletian’s system of tetrarchy) and the concentration of wealth in the Eastern half. Both of these developments left the Western Empire an easy target for the barbarians, who would soon come flooding through the gates.

Constantine is responsible for many developments that would be important in European and Byzantine civilization. Under his rule, the church gained the right to inherit property. Clergy were relieved from paying taxes.He convened and presided over the Council of Nicea in 325 and had a major role in the formulation of the Nicene Creed, thus setting a precedent for the state's involvement in settling matters of doctrine. Whereas previously Christians had met clandestinely in houses, now great basilicas were erected, as Constantine funded building projects all over the Empire, including Lateran basilica and St. Peters in Rome. He also funded building projects over important sites in Bethlehem and Jerusalem, creating the concept of the Holy Land while doing so. Most significantly for bibliophiles, however, are the developments in the history of the book. These grand basilicas and churches required equally magnificent copies of sacred texts so that services could be carried out. To that end he ordered Eusebius to arrange for fifty lavish copies of Scriptures to be prepared. Before Constantine's reign, Christian texts were copied into a small, inconspicuous codices. During this period, however, Christian texts came out of the closet, eventually resulting in the illuminated display Bibles of the early Middle Ages.

Bibliography

Brown, Michelle. In the Beginning: Bibles before the Year 1000. Smithsonian Books, 2006.

Cameron, Averil. “The Reign of Constantine,” The Cambridge Ancient History: The Crisis of Empire A.D. 193-337. Vol. XII. 2nd ed. Ed. Alan Bowman, Peter Garnsey, and Averil Cameron. 90.109.

–. “Late Antiquity,” Christianity: Two Thousand Years. Ed. Richard Harries and Henry Mayr-Harting. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001. 21-43.

Davis, Paul K. “Milvian Bridge,” 100 Decisive Battles from Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford UP, 1999. 78-82.

Eusebius. The History of the Church. Tr. G.A. Williamson. Penguin. 1965.

–. Life of Constantine. Tr. Averil Cameron and Stuart Hall. Oxford UP. 1999.

Lactantius. De Mortibus Perssecutorum. Tr. J.L. Creed. Oxford, Clarendon Press. 1984.

Nixon, C.E.V. and Barbara Rodgers. In Praise of Later Roman Emperors. Berkeley, U of California Press. 1994.

Dr. Rabia Gregory, an assistant professor in the Religious Studies department at the University of Missouri, is the focus of the first Teacher Spotlight of the new school year. Her primary interest is in medieval women’s religious literature, and she can often be found teaching courses at Mizzou on Historical Christianity, and Women and Religions. Dr. Gregory is a frequent visitor to Special Collections and has often brought her classes to learn about the primary sources we have here. We were pleased to get a chance to talk to her at the beginning of the semester.

Dr. Rabia Gregory, an assistant professor in the Religious Studies department at the University of Missouri, is the focus of the first Teacher Spotlight of the new school year. Her primary interest is in medieval women’s religious literature, and she can often be found teaching courses at Mizzou on Historical Christianity, and Women and Religions. Dr. Gregory is a frequent visitor to Special Collections and has often brought her classes to learn about the primary sources we have here. We were pleased to get a chance to talk to her at the beginning of the semester.