Kelli Hansen

Nov. 2004

Photos: Andrew Hansen

Fuchs, Leonhart. De historia stirpivm commentarii insignes… Basileae, In officina Isingriniana, 1542. RARE RES QK41 .F7

The Division of Special Collections  houses some of the most valuable and significant resources in the holdings of MU Libraries. The materials in the collections range in time period from antiquity to the present and include medieval manuscript pages, examples of early printing, fine press books, and important scientific works from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, among many other things. These books are not only wonderful treasures; they also greatly enrich the educational and research experiences of the University's students, faculty, and staff.

houses some of the most valuable and significant resources in the holdings of MU Libraries. The materials in the collections range in time period from antiquity to the present and include medieval manuscript pages, examples of early printing, fine press books, and important scientific works from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, among many other things. These books are not only wonderful treasures; they also greatly enrich the educational and research experiences of the University's students, faculty, and staff.

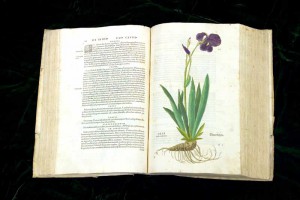

One book in particular exemplifies the abundance of information available to scholars in Special Collections resources. This book, De Historia Stirpium comentarii insignes (or Notable Commentaries on the History of Plants), was a gift from the Friends of the Library in 1963. It was published by a German physician and medical professor named Leonhart Fuchs in 1542. De Historia Stirpium is part of a long tradition of herbals, or books that describe plants and their medicinal uses. Before the sixteenth century, most herbals were based on folk traditions and Greek and Roman texts, not on scientific or artistic observation. Leonhart Fuchs broke with tradition by becoming interested in illustrating plants as they looked in nature instead of using conventional (and often bizarrely inaccurate) representations.

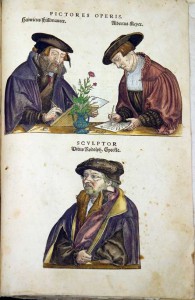

Fuchs hired three professional artists to help him with this undertaking: Albrecht Meyer, who drew the plants from life; Heinrich Füllmaurer, who transferred the line drawings to woodblocks; and Vitus Rudolph Speckle, who cut the blocks and printed the woodcut illustrations. The beautiful, densely illustrated book that resulted from their efforts contains some of the finest pictures of plants in the sixteenth century, many hand-colored under Fuchs’ supervision for the greatest accuracy. De Historia Stirpium is notable among early scientific books for its inclusion of the artists’ names and portraits in the back of the book.

Fuchs hired three professional artists to help him with this undertaking: Albrecht Meyer, who drew the plants from life; Heinrich Füllmaurer, who transferred the line drawings to woodblocks; and Vitus Rudolph Speckle, who cut the blocks and printed the woodcut illustrations. The beautiful, densely illustrated book that resulted from their efforts contains some of the finest pictures of plants in the sixteenth century, many hand-colored under Fuchs’ supervision for the greatest accuracy. De Historia Stirpium is notable among early scientific books for its inclusion of the artists’ names and portraits in the back of the book.

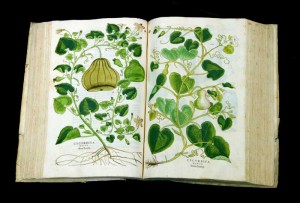

Fuchs’ interest in realistic representations accorded with the Renaissance ideal of naturalism, but it also served a practical purpose – he wanted his book to be a reference for his medical students and fellow doctors. While the images were cutting-edge for their time, Fuchs was not as revolutionary in the text, and his descriptions of each plant’s medicinal properties still draw largely on the writings of Greek and Roman authors such as Dioscorides, Galen and Pliny. Even so, Fuchs did encourage his own students to cultivate and study medicinal plants firsthand. Surviving copies of De Historia Stirpium often contain pressed plant samples, stains, and marginal notes that point to extensive use, and the copy belonging to Special Collections is no exception. In this way, De Historia Stirpium can give modern scholars insight into the ways early physicians studied and administered herbal medicines.

De Historia Stirpium was more than a lavishly illustrated compendium of remedies. The book also introduced many Europeans to the unfamiliar fruits, vegetables and plants being imported from the Americas. De Historia Stirpium contains the first description and illustration of over 100 species of plants, including pumpkins, squash, chili peppers, and maize, although some species are misidentified. It is thought that some of these plants were drawn from specimens or seeds Fuchs acquired and grew in his own garden.

De Historia Stirpium is one of the most valuable books in Special Collections, and it is also one of the most significant scholarly resources. This single book can be studied for its relationship to other herbals, artistic collaboration, scientific illustration, publishing history, the history of botany, and the history of medicine. In the same way, the materials housed in the Division of Special Collections allow students and scholars to explore a wide range of research topics by a variety of methods, from delving into rare historical and scientific texts to studying original examples of the book arts. Special Collections materials, including books like De Historia Stirpium, are not only treasures; they are also important resources open to use by all researchers.

De Historia Stirpium is one of the most valuable books in Special Collections, and it is also one of the most significant scholarly resources. This single book can be studied for its relationship to other herbals, artistic collaboration, scientific illustration, publishing history, the history of botany, and the history of medicine. In the same way, the materials housed in the Division of Special Collections allow students and scholars to explore a wide range of research topics by a variety of methods, from delving into rare historical and scientific texts to studying original examples of the book arts. Special Collections materials, including books like De Historia Stirpium, are not only treasures; they are also important resources open to use by all researchers.