Cartas Ejecutorias

Iconographies of Power

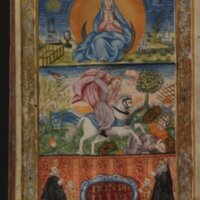

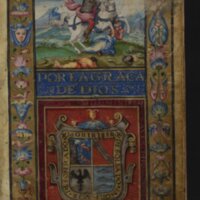

Carta executoria de hidalguía for Juan Molano of Casas de Reina, 1582. The quality of illumination and calligraphy in this ejecutoria indicates that it may be an example of less-professional, provincial production.

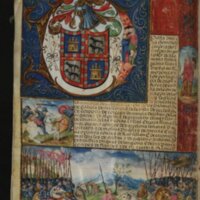

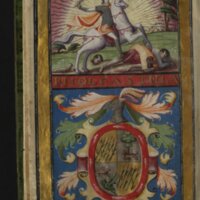

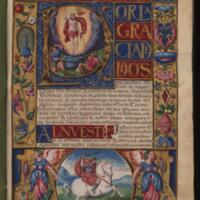

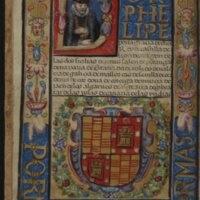

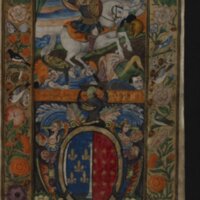

Cartas ejecutorias were created at the request of the plaintiffs in a successful hidalguía lawsuit and were intended to be shown to others: tax collectors, town councils, judges, and peers. They are often accompanied by lavish full-page illuminations with carefully selected subjects meant to express their owners’ status, orthodoxy, and loyalty to the Spanish crown. These illuminations draw on long-standing symbols and artistic traditions that would have been instantly recognizable to the documents’ various audiences. Miniatures depict the king, the royal family, the Virgin and Child, national patron saints such as Saint James, and the coats of arms belonging to the hidalgo’s family. Cartas ejecutorias also employ deliberately archaizing artistic and calligraphic styles, which are perhaps meant to emphasize the depth of the lineage and tradition that supported the hidalgo’s successful lawsuit.[5]

Although the text of the documents is somewhat formulaic, their illumination can vary widely in quality and style. The form and extent of the ornamentation was most likely related to the hidalgo’s budget; individual members of the nobility were not necessarily wealthy. The variation in styles and quality may also reflect the diversity of painters and illuminators at work in early modern Spain. There is evidence that successful hidalgos contracted with professional painters and illuminators in the larger cities to decorate their documents. Surviving documentation suggests that this type of illumination was expensive: around 200 reales, when the wages for an urban laborer are estimated at 10-11 reales per week.[6] However, there is also evidence that hidalgos took their ejecutorias back home with them and had them decorated by local artists, perhaps working at lower rates, in less polished vernacular styles. Both types of documents are in evidence in the examples shown here.

Por la cual vos mandamos

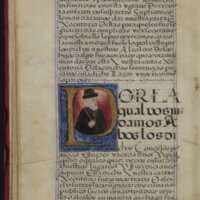

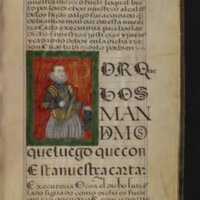

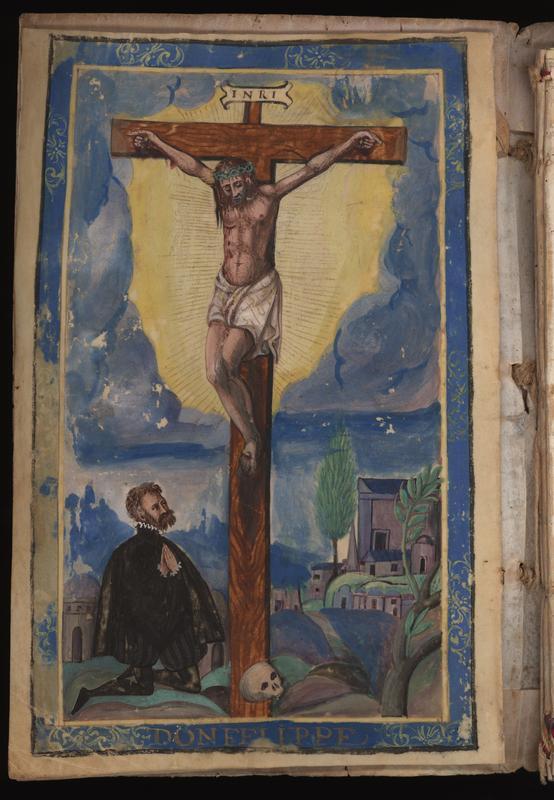

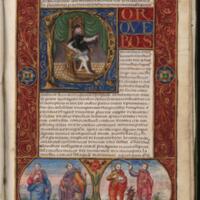

Church and state were inseparably intertwined in medieval and early modern Spain. All the cartas ejecutorias in this collection begin with an acknowledgement of the divine right of the King of Spain. Each document is written in the royal first person, in the name of the king, and is addressed to local officials. The imagery of the ejecutorias often emphasizes this royal authority by including recognizable portraits of the current ruling monarchs in the section that includes the final court rulings, which is usually prefaced by the phrase "Por la cual vos mandamos" (By which we order you).

Portrait of Philip II from Carta ejecutoria de hidalguía for Gonzalo Rodríguez Lobo and his sons Francisco Lobo and Garci Sanchez, 1569.

Portrait of Philip II from Sentencias y carta executoria de hidalguía for Bernardino de Godoy of Toledo, 1574.

Portrait of Philip II from Carta ejecutoria de hidalguía in favor of Diego López de Valcárcel the elder, and his children Diego López de Valcárcel, Gómez de Valcárcel, and Ana de Valcárcel, 1578.

Portrait of Philip II in Carta executoria de hidalguía dada a pedimiento de doña Guiomar de Alarcón Ulloa, 1593.

Santiago Matamoros

Santiago Matamoros (Saint James the Moor-Slayer) was a powerful national symbol in medieval and early modern Spain. According to medieval legend, St. James the Apostle preached in Iberia, then was martyred in Jerusalem. The legend states that angels transported his body to Compostela in northern Spain, where eventually the cathedral of Santiago was built, and a major pilgrimage site was established.

A later medieval legend states that during the Christian invasion of the Muslim Caliphate of Córdoba in the southern Iberian Peninsula, Saint James miraculously appeared to fight alongside Christian soldiers. Saint James became the patron saint of Spain in both of his guises: as a pilgrim and as a knight. The image of Saint James brandishing a sword from atop a white horse, along with the rallying cry of ¡Santiago!, were carried by Spanish Christian armies into their genocidal conquest of the New World.

Carta ejecutoria de hidalguía for Gonzalo Rodríguez Lobo and his sons Francisco Lobo and Garci Sanchez, 1569.

Carta ejecutoria de hidalguia a pedimiento de Juan de Alvarado difunto y Rodrigo de Alvarado su hijo, 1599.