Cartas Ejecutorias

Hidalgo Families

The Spanish word hidalgo is a modern contraction of the word hijodalgo – literally “son of something” – and expressed the idea that hidalgos had a known lineage and established family line. Hidalguía could be proven by providing witnesses to state under oath that the plaintiffs’ father and grandfather had been hidalgos, that they came from a lineage of Christians that were loyal to the crown during the constant wars against Muslims, and that their status was common knowledge in the area. The plaintiffs' town council, joined by a prosecutor for the monarchy, would usually contest the claim by alleging that the plaintiffs or their ancestors had not fulfilled their obligations as hidalgos, or had voluntarily paid their taxes in the past, or were of Jewish, Muslim, or illegitimate descent. If any one of these allegations proved to be true, it would nullify the plaintiffs’ claims to hidalguía.[4]

Because hidalguía was only inheritable through the paternal line, many cartas ejecutorias focus on proving and illustrating relationships between fathers and sons. The first three highlighted in this section reveal other family structures that were perhaps not as common among hidalgos. The hidalgos represented here include a single woman, the son of a village priest, and a man who had to prove that his cousin's carta ejecutoria applied to him, too.

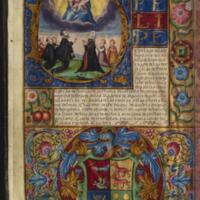

Guiomar de Alarcón Ulloa

This carta ejecutoria issues a patent of nobility in favour of Doña Guiomar de Alarcón Ulloa, resident of the town of Jaén in Andalucía. The document states that she was the daughter of deceased parents Diego Hernandez de Ulloa and Doña Catalina de Quintana, granddaughter of Pedro Hernandez de Ulloa and Doña María de Alfaro, and great-granddaughter of Diego Hernandez de Ulloa and Doña Catalina Lopez de Molina. Her six siblings are also mentioned in the document: Diego Hernandez de Ulloa, Luis de Arquellada Ulloa, Pedro Hernandez Ulloa, doña María Alfaro Ulloa, Doña Luisa de Ulloa and Doña Catalina de Ulloa.

The first part of the document deals with the proof of nobility of her father and uncle, Diego Hernández de Ulloa and Francisco de Ulloa, sons of Pedro Hernández de Ulloa, but really centers in the figure of their most noble ancestor, their grandfather Diego Hernández de Ulloa. Don Diego fought, almost a hundred years before this document was created, against the so-called “moors” during the war of Isabella and Ferdinand, the Catholic Monarchs. Some witnesses retell in their testimonies the story of how he defended the fortress of “Monte Xicar” (now called Montejícar) five years before of the fall of Granada. He was the alcaide (warden) of the fortress, and the carta ejecutoria includes copies of letters that were sent to him by both Queen Isabel and King Fernando. An exchange with Prince Juan is also mentioned. He is described by the witnesses as a brave and noble man, beloved and respected by everyone in Jaén. It is interesting to note that an important proof of nobility for Don Diego is the fact that he fought for Queen Isabel, who is mentioned with the utmost respect.

Doña Guiomar, as well as her sisters, mother, grandmother and great-grandmother, are only briefly mentioned. The fact that she asked for this document to be issued in her name, tells us that she had no man by her side, to fight for her rights. Her father is mentioned in the second half of the document as “deceased,” several times. The siblings are described by a witness as “minors,” which could mean she was the eldest surviving member of her family, which could explain why the ejecutoria includes her portrait, accompanied by a young girl, without the male members of her family by her side.

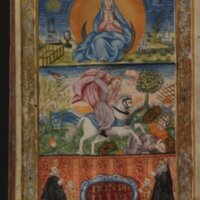

Bernardino de Godoy

When Bernardino de Godoy filed his lawsuit with the chancery court in Valladolid, the town council of Toledo claimed that he was the son of Gonzalo Mexía, the priest of the village of Añover, and was therefore illegitimate and ineligible to possess hidalguía. Bernardino de Godoy responded by calling witnesses who verified that he was indeed the son of Gonzalo Mexía, but that he had been born before his father took his vows as a priest. The date of his birth made Bernardino de Godoy legally eligible to be recognized as a legitimate natural son of the Mexía family. Relatives and acquaintances who had known him from the time of his birth testified that he had been raised as such.

The Sala de Hijosdalgo initially found in Bernardino’s favor, but the town and crown fought back, appealing this case multiple times over doubts about Bernardino’s legitimacy. Bernardino de Godoy was required to furnish his father’s certificates of ordination and provide archival evidence that the dates on these documents were not falsified. It took over twenty years to settle this suit, which was originally filed in 1553.

The Mexía and de Godoy family were prominent in Esquivias, the town Miguel de Cervantes called home for a time and later identified as the birthplace of Don Quixote. Two of the witnesses in this lawsuit were Mexías from Esquivias: Pedro Mexía (Bernardino’s uncle) and Ana Mexía (his aunt). Witnesses also included Bárbara Jiménez, a widow, and Mencía Gutiérrez, a nun at a nearby convent.

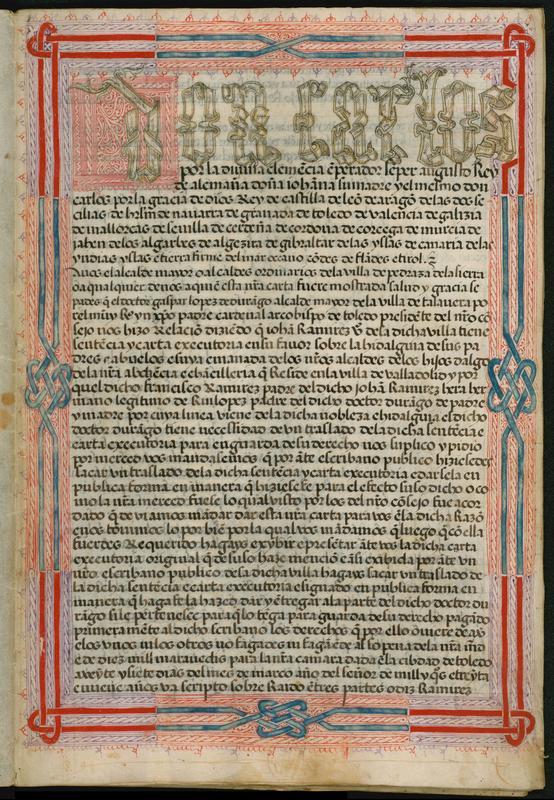

Juan Ramírez and Gaspar López de Durango

Juan Ramírez, a citizen of Pedraza de la Sierra, proved his claim to hidalguía in the chancery court of Valladolid in 1528. Twelve years later, his cousin, Gaspar López de Durango of Talavera, petitioned the Duke of Frías in Pedraza for an official copy of Ramírez’s carta ejecutoria to prove his own hidalgo status.

This document is that copy. It was written and attested by Blasco Sánchez, the Duke’s official notary, who compiled and transcribed all the briefs and minutes included in López de Durango’s request. Seven witnesses were called to verify that Gaspar López de Durango and Juan Ramírez were paternal cousins; Sánchez notes that of the seven, six were unable to sign their names to their testimony due to illiteracy, an interesting statement on education and legal testimony in early modern Spain. Their testimony is followed by the text of the Ramírez ejecutoria and a declaration from the Duke’s magistrate that it also applies to López de Durango.

Perhaps because of its status as a copy, this ejecutoria was not illuminated or illustrated beyond the decorative treatment of King Charles’ name on the first leaf.

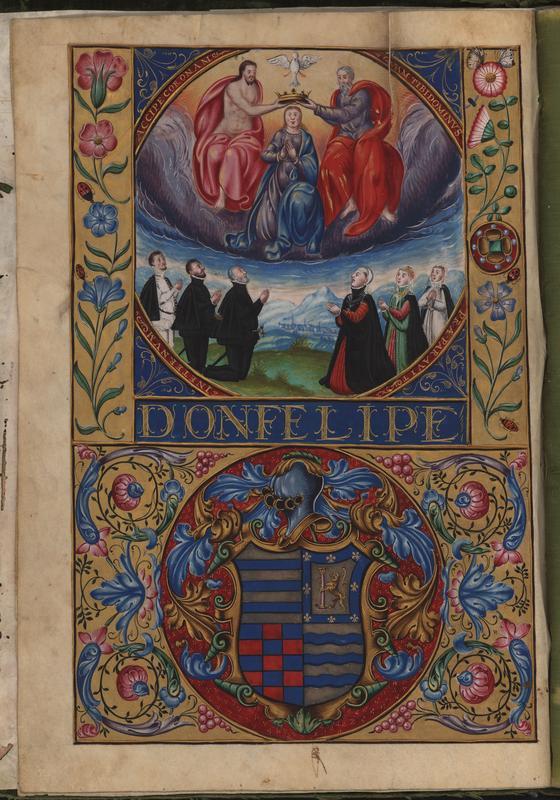

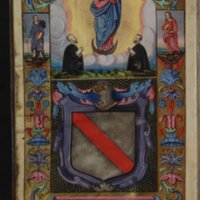

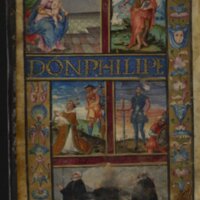

Family Portraits

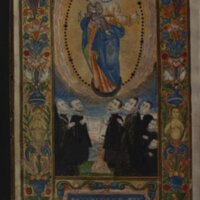

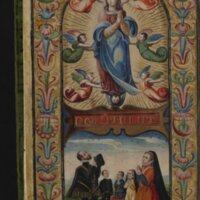

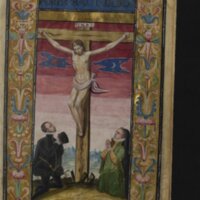

Many cartas ejecutorias feature portraits of their owners in prayer to various religious figures, most often the Virgin Mary and Christ Child. These portraits sometimes include multiple members of the family, both male and female. In some cases, the figures are labeled with family members' names, but in most cases, the women and children depicted are nameless. Although the names of the hidalgos' mothers and grandmothers are often included in witness testimony to prove their legitimate descent, the names of their wives are less frequently recorded. Children's names are included when they were parties to the lawsuit, which often happened if their father died before they were of legal age.

Gonzalo Rodríguez Lobo and his sons Francisco Lobo and Garci Sanchez, 1569. The sons' portraits appear to have been defaced.

The late Juan de Alvarado Salazar and his wife Doña María Guerrero (left) with their son Rodrigo de Alvarado and his wife and children (right), 1599.

This particular carta ejecutoria has portraits of two separate generations. This one illustrates the late Diego López de Valcárcel, his wife, Catalina Pinero, and their children, Diego López de Valcárcel, Gómez de Valcárcel, and Ana de Valcárcel, 1578.

Another couple illustrated in the carta ejecutoria of the Valcárcel family, possibly the late Diego López de Valcárcel and his wife Doña Elvira de Balboa, parents of Diego López de Valcárcel and grandparents of the children represented in the previous portrait, 1578. According to witness testimony, the second Diego López de Valcárcel died, and then his father died as well, leaving the children (and presumably their mother and grandmother) to pursue the lawsuit to its conclusion.