This post is part 4 of our continuing series on Dr. Juliette Paul's English 4300 class and their research on an early American manuscript in Special Collections.

by Amy Cantrall

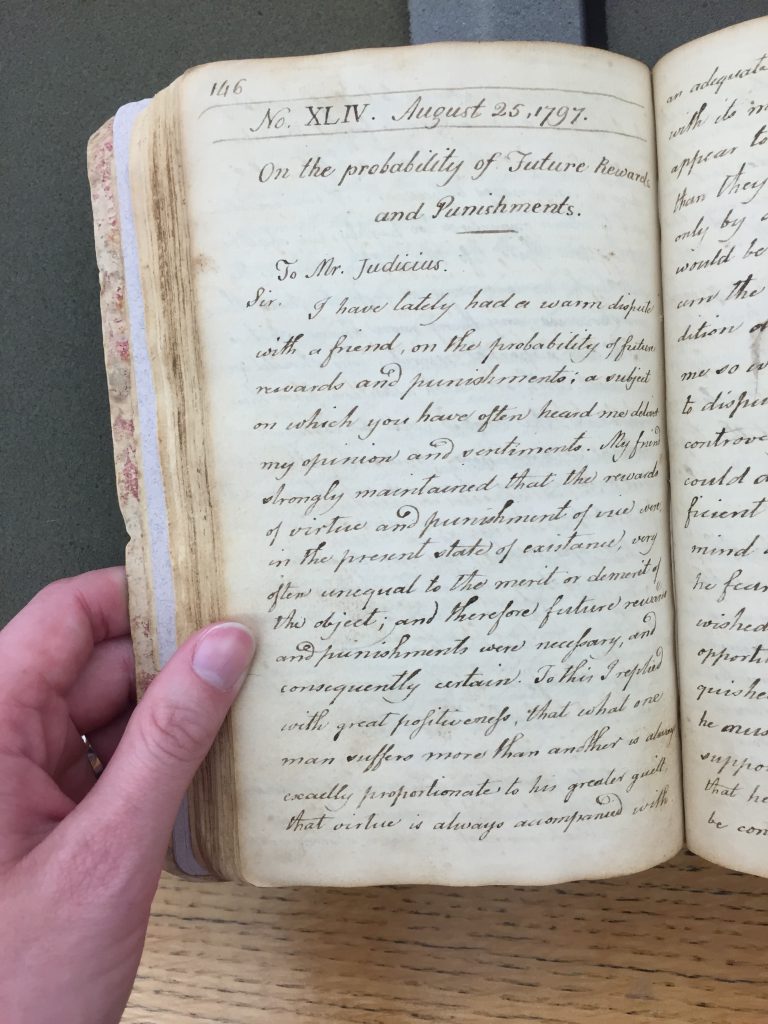

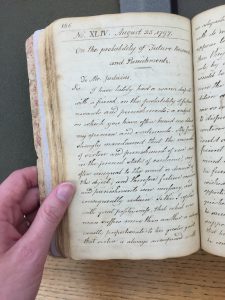

The pages of The Lucubrator are filled with advice, opinions, and contemplations about life. The very last essay casts a different tone: one of fiction, as it contains all the elements of storytelling. The story, dated as being written on August 25, 1797, is of the narrator coming across a hurt man on the road; it is entitled “On the Probability of Future Rewards and Punishments.” This last essay follows this stranger’s path through his life of misery, action, and adventure. It is a tale fit for modern novels—the man, sent to work at a young age, becomes involved in war as he grows older. Mistaken identities, seafaring adventures, piracy, and a strong-willed attempt to return home encapsulate this amazing story; enough to certainly keep readers on the edge of their seats to find out what will happen to the poor stranger who happened to come upon the narrator’s path.

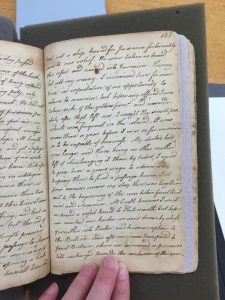

However, we don’t find out what happens to the narrator. Sadly, one of the many mysteries of The Lucubrator includes what has happened to the rest of the manuscript. The missing pages could suggest that there is a second volume of The Lucubrator, especially due to the fact that the story has no satisfying conclusion. The fictional tale ends with the sentence “Soon after we were transported to Great Britain, where we remained as prisoners till exchanged towards the conclusion of the war.” Although the story seems to be in the middle, the back page remains blank, with no further writings. The mysteriousness of the unfinished story captures our wonder for this stranger within the final ten pages of a mysterious manuscript. This story strikes a reader as intriguing also because it is not like the other essays, which are educational and moralistic; this one seems to be a complete work of fiction, pulled from the writer’s imagination. Its placement at the end of The Lucubrator could perhaps also be a way of filling up pages, as the American publisher Robert Bell did with Samuel Jackson Pratt’s novel Emma Corbett (1780); rather than waste valuable sheets of paper, he filled them (Pratt 233). If we are to believe this is what Noyes had intended, then it is possible that “On the Probability” was never a finished story.

However, we don’t find out what happens to the narrator. Sadly, one of the many mysteries of The Lucubrator includes what has happened to the rest of the manuscript. The missing pages could suggest that there is a second volume of The Lucubrator, especially due to the fact that the story has no satisfying conclusion. The fictional tale ends with the sentence “Soon after we were transported to Great Britain, where we remained as prisoners till exchanged towards the conclusion of the war.” Although the story seems to be in the middle, the back page remains blank, with no further writings. The mysteriousness of the unfinished story captures our wonder for this stranger within the final ten pages of a mysterious manuscript. This story strikes a reader as intriguing also because it is not like the other essays, which are educational and moralistic; this one seems to be a complete work of fiction, pulled from the writer’s imagination. Its placement at the end of The Lucubrator could perhaps also be a way of filling up pages, as the American publisher Robert Bell did with Samuel Jackson Pratt’s novel Emma Corbett (1780); rather than waste valuable sheets of paper, he filled them (Pratt 233). If we are to believe this is what Noyes had intended, then it is possible that “On the Probability” was never a finished story.

In an attempt to discover who James Noyes might have been, I came across one James Noyes’s almanac entitled An Astronomical Diary or Almanack, for the Year of Christian Aera, 1797. Similar to The Lucubrator, the Astronomical Diary contains a fictional tale entitled simply, “Humorous: A Humorous Tale.” This tale is an amusing story of two Englishmen who stay the night in a house with a corpse. After one of the men returns to what he believes to be his room, he climbs into bed unknowingly with the corpse—causing much fright for the servants when they believe the corpse has come back to life. This is a short, humorous tale; its presence near the end of an almanac seems to function as a way of entertaining readers, as almanacs mostly provide factual information and details about daily weather for planting and growing crops. In this way, the placement of the humorous tale is unexpected and not so straightforward; but it is understandable why it would be there. Similarly, the final essay of The Lucubrator is also a sensational and unexpected fiction, with its unfinished story leaving much for readers to question. I think this could very well be the same James Noyes, as both seem to like including fictional stories at the end of their writings.

Fictional stories and novels in early America provided a new scope of reading. With fiction, news stories could be presented in new ways and grow into new genres. As we have found with such popular novels as Emma Corbett, Susanna Rowson’s Charlotte Temple (1791), and Hannah Webster Foster’s The Coquette (1797), narratives that followed fictional lives often benefited readers by demonstrating strong moral conduct and warning against seduction. In this way, early novels were often didactic. But the two fictional stories I have chosen to examine, “A Humorous Tale” and “On the Probability of Future Rewards and Punishments” are not instructive. Because the latter short tale does not have a proper ending, it is unknown whether or not the author intended for a moral lesson or some sort of warning as the title implies. This is why I believe these fictions are of a different kind than we find in contemporary novels. They are used solely for the purpose of surprising and entertaining readers who expect advice and meditations in The Lucubrator and weather reports in the almanac.

Perhaps, in these short fictions, we can see one moment in the evolution of American fiction. If the author of “On the Probability of Future Rewards and Punishments” had turned the tale into a novel, I believe he or she would have written it in a single narrative voice, as was becoming popular during the period of the manuscript’s creation. From here on out, fictional storytelling (including short stories and novels alike) would only expand and develop further.

Works Cited

Noyes, James. An Astromonical Diary or Almanack, for the Year of Christian Aera, 1797. Dover: 1796. America's Historical Imprints. Web. 29 Apr. 2016.

Noyes, James. Lucubrator. N.d. MS. University of Missouri, n.p.

Noyes, James. The Federal Arithmetic; Or, A Compendium of the Most Useful Rules of That Science, Adapted to the Currency of the United States. For the Use of Schools and Private Persons. Published Agreeably to Act of Congress. Exeter: 1797. America's Historical Imprints. Web. 29 Apr. 2016.

Pratt, Samuel Jackson. Emma Corbett, Or, The Miseries of Civil War. Ed. Eve Tavor Bannet. Peterborough: Broadview, 2011.